Poverty

Americans spend hundreds of billions of dollars on food each year, and there’s so much to spend that money on; from organic produce to ethnic fare to your everyday milk and bread. With so many choices it’s hard to imagine that each year 33 million Americans suffer food insecurity; a nice way to say they don’t know where their next meal is coming from.

“In order to be in a good state of mind, you have to eat.”

Curstine Smith is the mother of three school age kids. The Hueytown woman is also one of those millions struggling to keep their families fed.

“It’s frustrating. There have been times when I didn’t have anything here that I could give, that I could prepare a meal from and that was something that hurt so bad. It’s a hurt you can’t really describe cause when you’re hungry, you’re hungry.”

Smith works 40 hours a week as a patient services representative at Children’s Hospital, but her paycheck isn’t enough to make ends meet. So, she works another 10 to 20 hours a week cleaning houses and offices. And sometimes, that’s still not enough.

“The thing is I work hard everyday trying to take care of my three children. I went through a horrible divorce and it put me in a situation where I’m trying to support my three children and myself to try to keep everything going, sometimes I have to go out and ask for support.”

Lynn Parker is the Director of Child Nutrition Programs for the Food Research and Action Center, or FRAC. It’s a Washington D.C. based non-profit organization that serves as a clearinghouse for information on hunger.

“People think of hunger as being something like they see in a developing nation where there’s famine, but the kind of hunger we see in the United States is when families consistently skip meals, eat less than they should, parents going a day without food so their kids can eat.”

Parker says people who go without food are sicker and end up needing more medical care than those who eat a well-rounded diet. The cost of caring for the hungry is passed on in higher medical bills for everyone else — which is getting to be expensive. Here in Alabaman 12-percent of residents suffer from food insecurity, that’s slightly higher than the national average and Parker says that’s only going to go up.

“There are more and more people who are in lower wage jobs, or unemployed, but if they’re employed they’re in lower wage jobs. What hunger gets down to, really, is resources. When people have very low incomes their food budgets are stretched to the max.”

It’s not just hungry families who worry about their resources being stretched thin, many of the pantries people often turn to for hlep are having a hard time keeping up with an increasing demand.

Guy Davis oversees a pantry in Hueytown. It hands out food once a month to more than 200 families. Just a week before speaking with WBHM, Davis says they were afraid they wouldn’t have enough for everyone.

“We had about three-fourths of the food we needed, so we knew we were in trouble, but we just trusted in the Lord. Thursday he gave us two-thousand pounds, Friday he gave us two-thousand more.”

Davis’ pantry is one of more than 100 pantries partnered with the United Way Community Food Bank in Birmingham. Right now the food bank’s warehouse has about 500-thousand pounds of food in stock, but that’s only about what they like to keep on hand. Agency Relations Coordinator Stacy Farry says it’s a constant struggle to keep the warehouse full.

“There is a constant need for that donation from the private sector as well as government and otherwise, to make this happen, to have the food here to provide for the agencies to actually get it to the people who need it.”

FRAC’s Lynn Parker says food banks all over the country have seen a decrease in donations over the last few years, thanks to the rough economy.

“It’s a combination of things, one is that the companies that have been contributing food over the years, it’s not that they’re getting stingier; they too are feeling the economic pinch and are becoming more and more efficient. And I think also that people around the country who have donated food and money to these emergency food sites are also feeling the economic pinch.”

Birmingham United Way Community Food Bank Executive Director Larry Logan says the staggering economy explains some of that, but not all. He says there’s a more basic reason people aren’t giving.

“They hate to admit that two blocks from their house is someone who hasn’t had anything to eat in a couple of days. And you know it’s easy to say that one of your third world countries are going hungry, you wouldn’t think that here in America, as much product and groceries and things as we have, that there’s actually hungry people out there; it’s hard to realize for some people.”

Back at the food pantry in Hueytown, families are lined up, waiting patiently for their number to be called and food loaded into their cars. Ethel Halloway has been coming to the pantry for four months; she says gas and milk prices got so high, she just couldn’t make her money stretch far enough. Halloway says by the time she’d buy her medicine and pay her bills, there was barely enough left over for groceries — she says she’s been eating better since coming to the pantry.

“It helps out a lot. Some of my medicines cost 125 dollars a month, so it’s real high. But if this subsitutes, then I can take what money I got and buy me some meat.”

Bessie Jean Williams says without the pantry’s help, there’s no way she’d be able to keep food in her house.

“They have helped me a lot. I’m just so grateful and thankful that there’s somebody that cares enough for us to help us.”

While these two ladies are willing to talk about the pantry there are others in line who seem ashamed to be there. And Curstine Smith understands where they’re coming from. She says it was hard to swallow her pride and ask for help that first time.

“It was an embarrassing thing to me, it was an embarrassing situation, I got to a point where I wanted to just put something over my head so nobody would see me because I felt like I was just degrading myself, I was just nobody.”

But Smith’s not nobody; she’s one of more than 500-thousand Alabamians who struggle to feed their families. And with almost 15-percent of the state’s residents living at or below the poverty line, many more like Smith may be turning to food pantries for help.

For U.S. pairs skater Danny O’Shea, these Olympics are 30 years in the making

Danny O'Shea turned 35 at his first Olympics, after three decades of skating and two reversed retirements.

Want a mortgage for under 3% in 2026? Meet the ‘assumable mortgage’

Low mortgage rates from the COVID era might still be attainable for homebuyers, if they find the right house and have the cash.

Epstein files fallout takes down elite figures in Europe, while U.S. reckoning is muted

Unlike in Europe, officials in the U.S. with ties to Epstein have largely held their positions of power.

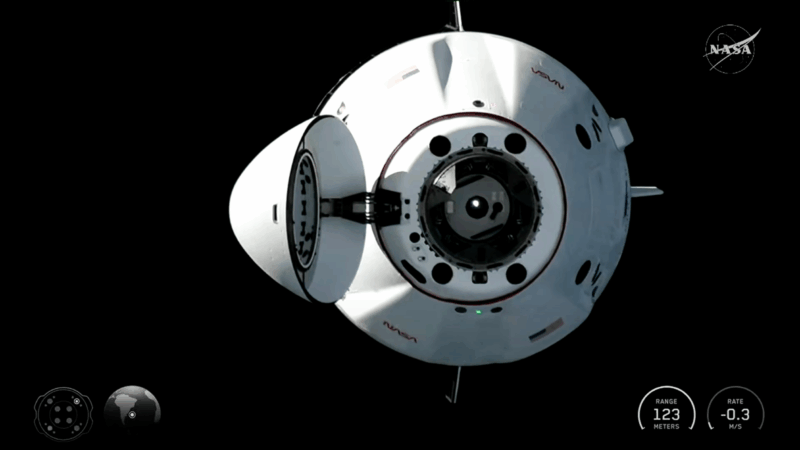

Four people on NASA’S Crew-12 arrive at the International Space Station

The crew will spend the next eight months conducting experiments to prepare for human exploration beyond Earth's orbit.

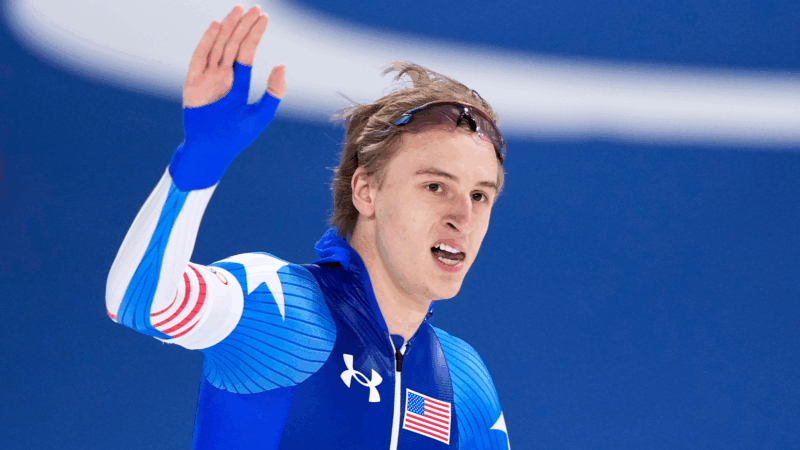

American speedskater Jordan Stolz wins second Olympic gold with 500-meter race victory

With the win, Stolz joins Eric Heiden as the only skaters to take gold in both the 500 and 1,000 at the same Olympics.

US military reports a series of airstrikes against Islamic State targets in Syria

The U.S. military says the strikes were carried out in retaliation of the December ambush that killed two U.S. soldiers and one American civilian interpreter.