Why these women break the law to sell their eggs for IVF

MUMBRA, India — The afternoon sun shines on the woman in a commuter-town café, highlighting her almond-shaped eyes and pale skin, a look often sought after by couples who need an egg to have a baby.

“I have good eggs,” she laughs — good enough that she guesses she’s a biological mother to at least 30 children.

The 34-year-old woman requests we withhold her full name, because to survive, she sells her eggs, which is illegal in India. NPR refers to her by “H,” the initial of her first name.

Producing multiple eggs isn’t easy on the human body. Typically a woman in her reproductive years will release one egg a month — it’s either fertilized or flushed out with her period.

But when H has a commission, she’ll inject herself with hormones for days to stimulate her ovaries to produce 20 to 30 eggs at a time. While she’s under anesthesia, a health worker inserts a long thin needle through the wall of H’s vagina to retrieve those eggs from her ovaries.

H says doctors who have extracted her eggs have told her that she typically produces about two dozen at a time and that they are high quality — that is, they’re more likely to be fertilized.

H says that, alongside her good looks, it’s why she’s in demand. She estimates she has undergone 30 retrievals in the past five years. Whether the number is correct or not, it’s clear that she does this regularly.

If each of those retrievals produced one live baby, she’d be a biological mother to at least 30 children. She thinks there are far more. She boasts: “If they’ve harvested 20 eggs from my body, you can assume 10 kids have popped out at least.”

Over the years, H has been paid a high of $800 for her eggs and a low of $280 for a yield of eggs. Even that amount is more than the monthly wage of most jobs in India.

Breaking the law to survive

Women selling their eggs illegally is an open secret in the Indian fertility industry. Even though the for-profit industry relies on their biomaterial to keep operating, NPR found that the women whose eggs are harvested are usually poor and vulnerable to exploitation but have no recourse because they operate in a black market.

It’s unclear how many women sell their eggs in India.

H says women like her hide in plain sight. She says, “There are so many who are literally running their houses on egg donation.”

The fertility industry and the women themselves refer to what they do as egg donation. NPR found that in India, the money a woman is paid varies according to her looks, her education, her caste and the health of her eggs (based on an ovarian scan and blood tests checking the woman’s hormone levels). It echoes another largely unregulated market for eggs: the United States.

Selling her eggs is how H has survived since she left her unhappy marriage and was left homeless. H’s ex-husband received custody of their two children, and she drifted into the port city of Mumbai. She had no way of paying rent, and she recalls a girlfriend telling her: “You are beautiful — you are young. Sell your eggs and get some money. I’ve done it. Lots of girls do it.”

H didn’t understand. She’d never been told the basics of reproduction. Her girlfriend said: “You are just providing a part of your body to another person, so they can have a baby.”

Why selling eggs became illegal

Critics say this illegal market exists because India radically constrained the supply of human eggs after the government passed laws in 2021 to regulate its wild-west fertility industry.

Couples, gay and straight, as well as single men and women began flocking to India around 2002, when the country allowed foreigners to access commercial surrogacy. That made India a one-stop shop for baby making: A person could obtain sperm, eggs, embryos, a surrogate — all for a fraction of the price in the United States. India became known as a “global baby factory.”

Sneha Banerjee, an assistant professor at the University of Hyderabad in India, who extensively studied India’s reproductive industry, says the first moves to curb this industry began after a Japanese couple had a baby via a surrogate and an egg donor. The couple divorced before the baby was born, and the Indian Supreme Court had to rule on who the baby’s legal guardian was. “That was the first time that the current government took notice of this issue,” Banerjee says.

The new Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Act says a woman can donate her eggs only once and only to one other couple. She must be between 23 and 35 years old, must have been married at least once and must have a child age 3 or older.

But those tight restrictions have constrained supply at a time when demand is surging in India. Indian women are waiting longer to have children, when they’re less fertile.

And “the harsh realities of India [are] that we are a highly unequal society — there are a lot of poor people,” says Prabha Kotiswaran, a professor of law and social justice at King’s College London. She studies the fertility industry’s impacts on women. “There’s a lot of need,” she says, and women are bearing the brunt. “In that context, if you bring about a law that essentially shuts down a certain sector, it may be well-intentioned, but it is bound to have unintended consequences.”

The workings of the black market

Kotiswaran says soon after the law was implemented, she found that “there was a vibrant market in paid egg donation.”

The black market for human eggs exists in India because there’s no central registration of women who have donated their eggs. Women are “traveling from one city to the other, one state to the other,” says Dr. Duru Shah, the scientific director of an upscale Mumbai clinic. She also formerly served as the president of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India. “If an egg donor comes and tells me, ‘I haven’t donated anywhere,’ how do I know? I don’t know.”

H, who sells her eggs to survive, says most clinics don’t even look hard at the IDs of women whose eggs they’ve commissioned. If they want your eggs, she says, “they’ll find a way.”

H says she uses two fake IDs that list her as being under 30 because she’s afraid of aging out of the business. H is Muslim, but when needed, she passes herself off as a recent convert to Hinduism. That’s because clinic directors say some couples request eggs from a woman whose faith matches theirs.

And despite the law saying women should be stimulated to produce only around seven eggs at one time, H says she’s routinely stimulated to produce around two dozen eggs.

A critic of the new laws, Dr. Aniruddha Malpani, the co-director of a Mumbai fertility clinic, says there’s a strong commercial incentive for fertility clinics to stimulate women to produce more eggs: the more eggs a clinic can harvest, the more couples it can treat from just one woman it has paid.

Critics say there’s not enough oversight of this industry in India, where more than 6,800 fertility clinics operate but just over 2,500 have been registered since the new laws came into place.

Recruiting for egg donation online

When clinics need eggs for their patients, they often work through intermediaries, known as assisted reproductive technology (ART) banks, which according to the new laws, are meant to screen women for egg donation. The ART banks, as they are known, rely on people known as agents.

Like Ruby, 34. She asked that we use only her first name — her work isn’t legal. She says in a month, she gets about a dozen requests over WhatsApp for women’s eggs, like for example, “a clinic seeking a woman with an O-positive blood type, tall and pale.” She finds recruits through her networks and social media advertisements. Ruby gets paid a lump sum for each referral. She takes a cut of between $50 and $100 and then passes the rest on to the woman whose eggs have been harvested.

Critics say that the indirect chain allows fertility clinics to claim they are not paying women for eggs.

Ruby says her recruits are mostly poor. Many of them have alcoholic husbands. “Others lost their husbands. Some have financial difficulties.”

Why they risk breaking the law

Thirty-four-year-old Abirami lives in a slum in the southern city of Chennai. Like all the other women interviewed for this story, she and her friends asked to use only their first names, because they don’t want to risk getting in trouble.

She and her girlfriends walk us through their homes: each a tiny room in a row of tiny rooms down a tight alleyway, the interiors painted blues and purples. We meet Manimeghalay, who sold her eggs to pay her kid’s school fees. Anju, who sold her eggs to pay her son’s medical bill. Alamelu, who used the money to pay for her alcoholic husband’s funeral — and then, to fix a leaking roof.

Abirami assembles plastic toy guns for about $3 a day. Twice, Abirami says, she sold her eggs for about $300 to pay rent and feed her two daughters.

Abirami says she first heard about selling eggs from her neighbor while standing in line at a water pump. “Tell me where I can go and do it,” she pleaded.

When she told her husband, he accused her of being promiscuous — there’s a perception in India that egg retrieval is related to sex work. “He doesn’t understand the difference between thick and thin,” Abirami sniffed.

“The moment my husband left for work,” Abirami recalls, she and her neighbor sneaked out to a fertility clinic by bus. “I am illiterate,” Abirami explains, so she counted the stops to remember the route. It was “seven stops away.”

Abirami says that in the fertility clinic, she was hustled into a room where a nurse filled a form and told her to sign it with her thumbprint. Days later, she was being stimulated with hormones to produce more eggs.

Abirami says for her, the process was painful. “I thought the nausea would kill me,” she says. Her stomach swelled, which can be a sign she was overstimulated. Despite the pain, she sold her eggs again, two years later.

Vrinda Marwah, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of South Florida, investigated India’s fertility industry and says the new laws have made the lives of vulnerable Indian women even more precarious.

“You’ve told yourself you’ve done something, but actually you’ve only made it worse,” she says, referring to the legislators who formulated this law. “You’ve created a black market, which means the people participating in it have no protections — they have no bargaining power. If something goes wrong, they’re already doing something criminal, something illegal. So who are they going to turn to for help?”

A troubling incident

H, who sells her eggs to survive, says she couldn’t ask anyone for help when two years ago, a male agent sent her to a hospital to have her eggs extracted — and things did not go well.

H says she emerged from the anesthesia with swollen eyes, cuts near her lip and welts on her back, and she was wearing a diaper. H didn’t report the incident. She was scared she’d get in trouble for selling her eggs.

H says she fled the hospital as soon as she could. “If that man,” she says, referring to the agent, “did something to me, God will punish him.”

And in September, H claims an agent stiffed her out of money for an egg retrieval conducted at a major Indian fertility clinic, Akanksha Hospital.

H says she called the hospital to plead for payment. “We paid the agent,” she recalls a woman at the hospital telling her. “This is between you and the agent.”

Dr. Nayana Patel of Akanksha Hospital did not comment on that specific incident but said in an emailed statement that they obtain donor eggs from ART banks and are “in full compliance.” Patel wrote: “all payments are made directly to the ART banks in accordance with the specified law, and therefore maintain full compliance.”

H, meanwhile, is now late paying rent. To make up for lost income, she’s taking drugs to speed up her next period, so she can be stimulated again to produce more eggs.

Luring girls to produce eggs for sale

Amid the demand for eggs, a lawyer for a teenager says that when she was 13 years old, she was lured into selling her eggs to a branch of one of India’s largest fertility clinic franchises, Nova IVF Fertility. That took place in the northern Indian city of Varanasi, and the girl’s family filed a complaint with police.

Her parents asked us not to use their daughter’s name — they say their daughter has been socially stigmatized and dropped out of school after people found out she sold her eggs. “I couldn’t stand the gossip about me,” she told NPR at the office of Guria, a charity that works to protect child-trafficking victims.

The teenager, now 15 years old, told NPR that about two years ago, one of her neighbors told her that if a doctor took out her eggs, she’d get $180 — triple what her mother makes in a month as a cleaner. The teenager says she didn’t really understand — eggs? “A chicken egg can only come from a hen,” she laughs. But she really wanted a phone.

The teenager calls the woman “auntie,” a sign of respect to an elder in South Asia. And auntie got the teenager a fake ID and told her to dress like she was older. The teen smeared vermilion powder on her hair parting and put rings on her toes — in India, these are signs of a married woman.

With that, a contracting company signed off on the teenager having her eggs harvested and directed her to Nova IVF Fertility. For the next 10 days, the teenager skipped school to be stimulated with hormones and have her eggs extracted.

The teenager’s lawyer, Krishna Gopal, says he believes other minors are being lured into having their eggs harvested but says families have no incentive to come forward.

“The big people have not been touched,” he says. Gopal says Nova IVF Fertility hasn’t faced any punishment, including the doctor who extracted the teenager’s eggs. “No action has been taken against them.”

Nova IVF Fertility said in an emailed statement that the teenager was screened by a separate company that signed off on her having her eggs harvested — and that they had no way of knowing the teenager’s real age.

Can the black market be curbed?

NPR spoke to a senior member of the regulatory board that oversees the implementation of India’s assisted reproductive technology laws. She spoke on condition of anonymity because she’s not authorized to speak to the media. She told NPR that the new fertility laws were meant to protect women from being exploited through the commercial sale of their eggs. She said she was not aware that the practice is still continuing. She said she was not aware of any plans to create an egg donor registry.

Kotiswaran, the law professor at King’s College London, says the best way to curb the black market for human eggs is to legally compensate the women who provide them — not to pay for their eggs but for the labor involved in generating those eggs and having them extracted.

With the additional exception of surrogates, everyone else in the for-profit fertility industry, she says, is paid for their work. “This is a sector that’s generating so much profit,” she says, but “without the women, the sector wouldn’t exist,” she says. “We allow every stakeholder in the sector to make as much money as they want off the women’s bodies, but then you don’t want to pay the women themselves. So that is my fundamental problem.”

Preparing to sell eggs once more

Weeks later, we again meet H.

She’s bloated. Nauseous. Struggling to breathe. Her ailments suggest signs she was overstimulated to produce eggs — very rarely, that can be fatal. She tells us in a downtown Mumbai café, “I know this will kill me, but we’ll all die someday, right?”

Discussing her death is as casual for H as talking about the black eye she’s nursing. Her boyfriend had punched her a few days before. It’s nothing, H insists. “I bruise easily.”

What comforts her, she says, is thinking about her children, her 11-year-old-daughter and 13-year-old son. The ones she birthed herself. They’re being raised by her ex-husband.

She says that whenever she can, she gives them money. “They say I don’t have to, but my heart doesn’t listen,” she says. “After all, I am a mother.”

She pushes back her chair to leave. She’s got word that she’ll be able to see them if she can leg it across town in half an hour.

Diaa Hadid and Shweta Desai reported this story from Mumbra, Mumbai, Chennai and Varanasi, India. Anupama Chandrasekaran contributed reporting from Chennai.

Transcript:

MICHEL MARTIN, HOST:

A woman in India estimates she has dozens of biological children, and she says there are many more women like her because India has a thriving black market for human eggs. NPR’s Diaa Hadid and producer Shweta Desai investigated the story across India.

DIAA HADID, BYLINE: We meet H in a Mumbai cafe, couples who need a human egg to have a baby, like how she looks – pale skin, a pretty smile. H asks we don’t use her full name because her survival depends on work that is illegal in India. She doesn’t want to get caught. H estimates that over the past five years, she’s harvested her eggs for money at least 30 times. If each time produced one baby, she’d have some 30 biological children. H is sure she’s made more babies than that.

H: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: H says, “you can assume I’ve made at least 10 kids from me each time I’ve had my eggs harvested.” She says, “I’m that fertile.”

H: (Laughter).

HADID: Producing those eggs isn’t easy. When H has a commission, she’ll inject herself with hormones for days. She says it stimulates her ovaries to produce about two dozen eggs. Under anesthesia, a doctor will insert a long, thin needle through the wall of H’s vagina to retrieve her eggs from follicles on her ovaries. Depending on the client, H makes anywhere from $280 to $800. Even the lowest amount is more than the monthly wage for most jobs in India. Women selling their eggs is an open secret in the Indian fertility industry, but it’s unclear how many women do it. Off tape, H tells this to producer Shweta Desai, who interprets.

SHWETA DESAI, BYLINE: There are so many of them who are doing this while literally running their houses on egg donation.

HADID: This is often called egg donation, but selling her eggs is how H has survived since she left her husband. He took their two children. H was homeless. And a girlfriend told her, you’re young and pretty. Sell your eggs.

H: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: Her girlfriend said, “lots of girls do it. I’ve done it.” Critics say this illegal market exists because India radically constrained the supply of human eggs after the government passed laws to regulate its fertility industry in 2021. The laws say a woman can only donate her eggs. She can only do it once. Supply was constrained as demand surges because women here are waiting longer to have children. Meanwhile…

PRABHA KOTISWARAN: Women don’t have enough jobs, and there’s a lot of need.

HADID: Prabha Kotiswaran studies the fertility industry’s impacts on women. She’s a professor of law and social justice at King’s College London.

KOTISWARAN: In that context, if you bring about a law that essentially shuts down a certain sector, it may be well-intentioned, but it is bound to have unintended consequences.

HADID: Unintended consequences. Kotiswaran says soon after the law was implemented, she found…

KOTISWARAN: There was a vibrant market in paid egg donations.

HADID: That market can exist because there’s no central registration in India. So there’s no way of knowing how many times a woman has donated her eggs. When clinics need eggs for their patients, they often work through intermediaries who rely on people called agents like Ruby (ph). She asks we only use her first name. Her work isn’t legal. In a month, Ruby gets about a dozen requests for egg donors, mostly over WhatsApp.

RUBY: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: Ruby says a demand is for women who are pale and pretty like H. She finds them through her networks and social media ads. She gets paid for finding the women. We found this is how clinics and their intermediaries can claim that they aren’t paying women for eggs. They’re paying agents for recruitment. Ruby takes a cut between 50 to $100 and passes the rest on to the women whose eggs have been harvested.

Vrinda Marwah is an associate professor at the University of South Florida. She’s researched this industry and says the new laws are harming people who are already vulnerable.

VRINDA MARWAH: If something goes wrong, they’re already doing something criminal. So who are they going to turn to for help?

HADID: H, who sells her eggs to survive, says she couldn’t ask anyone for help when two years ago, a male agent sent her to a hospital to have her eggs extracted. H says she emerged from anesthesia with swollen eyes, cuts on her lip, welts on her back and was wearing a diaper.

H: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: H fled the hospital as soon as she could.

H: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: H says, “if that agent, that man did something to me, God will punish him.” Amid the demand for eggs in the northern city of Varanasi, a 13-year-old girl was lured into selling her eggs to one of India’s largest fertility clinic franchises. Her parents request we keep her identity anonymous. The teenager says about two years ago, a neighbor who happened to be an agent told her she’d get $180 for her eggs. The teenager says she didn’t understand. Eggs, like a chicken?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: But she really wanted a phone. The teenager’s lawyer, Krishna Gopal, believes this is happening to other minors, but there’s no incentive for families to come forward.

KRISHNA GOPAL: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: He says the clinic that extracted the teenager’s eggs, Nova IVF Fertility, hasn’t suffered any consequences. Nova IVF Fertility said in an emailed statement that the teenager was screened by a separate company that signed off on having her eggs harvested, and they had no way of knowing the teenager’s real age. We spoke to three members of the board that advises the health minister on the implementation of India’s fertility laws. They requested anonymity. They aren’t allowed to speak to media. None were aware that clinics were buying eggs from women through intermediaries. Kotiswaran, the law professor, says the best way to curb the black market for human eggs is to legally compensate the women who provide them.

KOTISWARAN: We think there should be contracts that are drawn up in favor of the women.

HADID: She says without the women supplying their eggs, couples trying to have a baby in India wouldn’t have options.

KOTISWARAN: There is an entire industry that’s living off these women’s biomaterial. But then you don’t want to pay the women themselves.

HADID: Weeks after we first met H, who sells her eggs to survive, we reunite in a Mumbai cafe. She’s bloated, nauseous, breathless. They’re all signs H was overstimulated to produce eggs. In rare cases, that can be fatal.

H: (Non-English language spoken).

HADID: H says, “I know this will kill me, but someday we’ll all die, right?”

Diaa Hadid, NPR News, with Shweta Desai in Mumbra, Chennai, Varanasi and Mumbai.

(SOUNDBITE OF BRAMBLES’ “SUCH OWLS AS YOU”)

How the West was won: K-pop’s great assimilation gambit

The crossover hits stacking Grammy nods this year have little in common with the culture that birthed them — but they're winning the chart game.

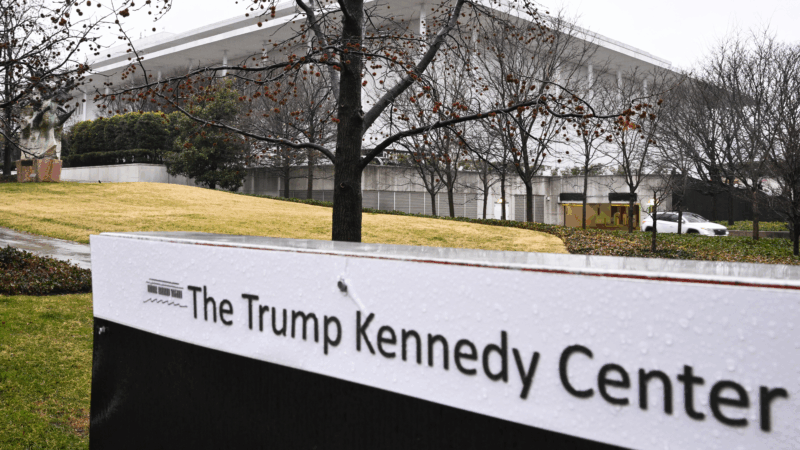

More staff shakeups at the Kennedy Center

The departures include Kevin Couch, who was announced as the Kennedy Center's senior vice president of artistic planning less than two weeks ago.

Medicare Advantage insurers face new curbs on overcharges in Trump plan

Federal officials have a plan that could curb billions of dollars in overpayments to Medicare Advantage plans. But will they follow through on it?

Border czar says he plans to “draw down” ICE and CBP operations in Minnesota

Tom Homan, who took over leadership of the surge in Minneapolis, says he is working on a plan to reduce the force of federal agents in the Twin Cities.

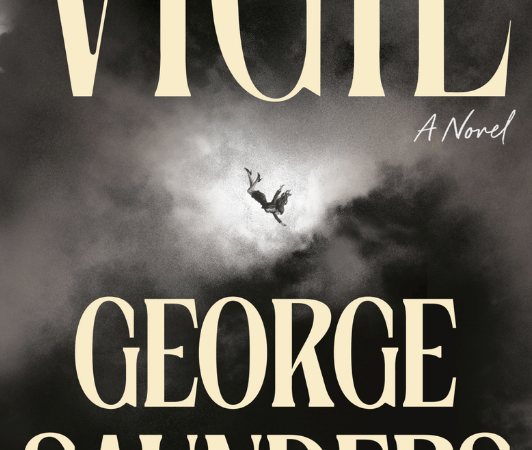

George Saunders’ ‘Vigil’ is a brief and bumpy return to the Bardo

The Bardo is a Tibetan Buddhist idea of a suspended state between life and death. Saunders explored the concept in his 2017 novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, and circles back to it again in his new novel Vigil.

Former NBC producer tells her own story about Matt Lauer in ‘Unspeakable Things’

Brooke Nevils was working for NBC at the Sochi Olympics when, she says, she was sexually assaulted by Today Show host Matt Lauer — a claim he denies. Nevils' new memoir is Unspeakable Things.