Why the origin of the word ‘dog’ remains a mystery

They’re known as man’s best friends, fur babies, pooches.

But the most widely used word for these beloved animals — “dog” — is also a great linguistic mystery.

“The most everyday, commonplace words are often the most mysterious,” said Colin Gorrie, a linguist who has written about the origin of “dog.”

Descended from wolves, dogs were among the first animals to be domesticated, and their close bond with humans can be traced back thousands of years. Much like the animal itself, the word used to describe canines has evolved over time; “dog” only became the standard term within the past 500 years or so, according to Gorrie.

“This is a process that we see over and over again,” he said. “I think what the source of it is — is the fact that dogs live with us so much and we have such an emotional association with dogs, they become parts of our family and they attract these kinds of pet names.”

From insult to standard pet name

Centuries ago, dogs were more commonly called “hounds” — a term derived from the Old English word “hund.” Today, “hound” typically refers to a specific breed of dog, but back then, it referred to all domestic canines, according to Gorrie.

Early forms of the word “dog” did appear in land charters and place names over a millennia ago. But most notably, during the Middle English period from roughly 1100 to 1450, “dog” was often used as an insult directed at people.

“ The use of terms for dog to insult people are pretty common historically and across cultures and we see it all over the place,” Gorrie said. “So not just in the history of English but in related languages of Europe and Asia.”

Over time, the positive emotions people felt toward the four-legged creature eclipsed some of the word’s negative, derogatory charge, he said. Around the 1500s, “dog” replaced “hound” as the standard term we use for the pet today.

“It’s very possible that the same word that you use as an insult, you can repurpose as a term of affection,” Gorrie said. “ Almost as if they’re reclaiming that word or using it ironically to show just how strong the affection is.”

Since “dog” became ubiquitous, it has continued to broaden in meaning. According to Gorrie, the term was used to describe an ugly woman in the 1930s, while in the 1950s, it came to mean a sexually aggressive man. Today, it is used widely as slang for a close friend.

Theories behind the origin of “dog”

While the evolution of “dog” is fairly clear, the mystery lies in its origins.

One theory among linguists is that “dog” comes from the Old English word “dox,” which was a term used to describe color, according to Gorrie. “It’s not entirely clear what it meant, but it probably meant something like dark or golden or yellow,” he said.

Another possibility is that it’s related to the Old English word “dugan,” which meant to be good, of use or strong, Gorrie added.

Part of the difficulty in tracing the origin of the word “dog,” he said, is that dogs have been part of human life for a very long time. That’s also true for common words such as “boy” and “she,” as well as animal-related ones like “pig” and “hog.”

“ There are theories about some of them,” Gorrie said. “But dog is the one that’s the real mystery.”

Why dogs are a popular source for idioms

The term “dog” has also borne a range of sayings, such as “dog days of summer,” “dog-eat-dog world,” and “raining cats and dogs.”

People tend to use what’s ordinary in their day-to-day lives as sources of metaphors and idioms. But they also reflect changing times, according to Don Nilsen, a professor of linguistics at Arizona State University.

Nilsen gave the example of “dogfight,” referring to close-range battles between fighter aircraft, which became common starting in World War I. He said the term was inspired by how dogs chase each other. The same goes for “dog tag.”

“ Sometimes we put on a dog a collar so that we know who it belongs to so that it can be taken back to the right person,” he said. “Well, if you go in the military, you wear a little collar like a dog does, and we call them dog tags.”

Nilsen added that many of these idioms stem from humans’ close observations of dogs’ behavior and mannerisms — showing just how close the two are.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.

An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine — to play pretend — has long been thought to be unique to humans. A new study suggests one of our closest living relatives can do it too.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

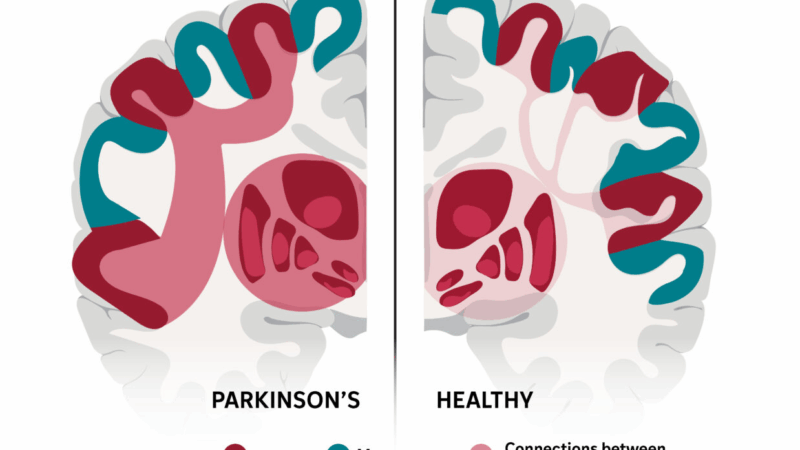

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.