Where are all the protest songs?

Among the historic wins, spirited if chaotic tributes and breakthrough moments for new talent at Sunday’s Grammy Awards, one small pleasure was the emergence of a new comedy duo. Twice during the evening, host Trevor Noah cozied up to its undisputed star, Bad Bunny, and ribbed him about not staging a performance. Pop’s champion of Puerto Rico and, as he joyfully suggested in his acceptance speech for album of the year DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, “todos los Latinos del mundo entero,” couldn’t bring his music to the Grammy stage because of a non-compete agreement with the NFL ahead of his upcoming Super Bowl performance. Noah’s chummy teasing did culminate in Bad Bunny ad-libbing a few fair-use bars of the album’s title track alongside a flash-mob style band. The exchange was charming, but it belied what the ceremony lost by not being able to feature music by its undisputed star.

Had Bad Bunny taken the stage, he could have — I feel safe saying, would have — offered something no other artist on the Grammy stage did: openly political music. The Puerto Rican star stood out amidst a notable array of celebrities who made statements in support of immigrants and against the violent actions taken against them and their allies by ICE. His two heartfelt acceptance speeches — one made his priorities clear when he said, “Before I give thanks to God, I’m going to say ICE out,” and the other was mostly in Spanish and dedicated to immigrants compelled to follow their dreams — were the most eloquent of a decent-sized handful of statements made during the main show and its much longer pre-ceremony. The array of “ICE OUT” buttons and incendiary offstage comments had many post-show analysts calling the event a fiery platform for protest and left Donald Trump fuming. Yet, as Craig Jenkins wrote in an excellent analysis of the night’s political rhetoric, gentility ruled the day, as it tends to do at such gatherings. Aside from that final, deeply emotional, deliberately bilingual moment, the night lacked much that matched the complex and urgent feelings raised simply by reading the news every day.

Given all that’s happened in the past few weeks — especially the collective shock of witnessing the deaths of Alex Pretti and Renee Macklin Good in Minneapolis — it’s difficult to care too much about the mild interventions pop stars made onstage or on the red carpet at the Crypto.com Arena. Little can ever be expected from guests at industry fetes, and even less from those who join the variety show to sing and play their hits. There have been some exceptions: In recent years, Kendrick Lamar (who made no references to immigration during his times onstage this year) confronted black incarceration and Trayvon Martin’s death in his 2016 medley performance; Macklemore and Ryan Lewis hosted a mass queer wedding officiated by Queen Latifah while staging “Same Love” in 2014. These stagings stand out not only for their power but for their rarity. And that’s not surprising: Protest is a word that’s tossed around a lot in the context of awards shows, but it actually has claimed very little space — and virtually no enduring musical space — within the mainstream pop timeline that such sanctioned industry gatherings preserve. Pop is defined by its appeal across demographic lines, while the conviction that meaningful protest demands demands that people take a stand and hold it. So while the question that’s often popped up on my social platforms recently — Where are all the protest songs? — does have an answer, beyond the occasional sing-along on Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World,” it’s actually rare for the outcries of the people to be channeled through a pop song, or in a pop setting.

Resistance and dissent through music historically take place much closer to the ground, emanating from the very spaces where people are putting their bodies on the line. It’s hard to reconcile the nebulous cost a Grammy winner or performer might suffer for speaking up — dropping streaming numbers, dipping ticket sales, maybe a social media backlash — with what we’ve seen people endure in real time in this still-young year. Bad Bunny stands out in 2026 not only for his historic success as the first artist win album of the year for a Spanish-language album, but because DtMF does explicitly enact resistance in songs like “LO QUE LE PASÓ A HAWAii,” calling out American imperialism, gentrification and the displacement of his fellow Puerto Ricans.

What makes Bad Bunny’s music so crucial is that he conveys these messages within a brilliant fusion of Latin musical styles, alongside expressions of romantic longing, seduction and the joy of partying. He’s able to do this because there is a robust tradition of political party music within global Latin pop, from Spanish flamenco to Nuyorican salsa to Mexican corridos. The same isn’t true for the time-honored American Top 40. Virtually none of the stars who performed Sunday could have pulled such a direct challenge from their own nominated albums. The only one available was Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs,” an anti-war tirade staged by a supergroup commemorating the late Ozzy Osbourne. That song is from 1970.

A lineage of protest songs does exist within rock and soul music, and it was represented at the Grammys by winners and nominees in categories excluded from the televised ceremony. Mavis Staples, whose message songs as part of The Staple Singers helped soundtrack the activist 1960s, won two awards in the Americana and American roots categories; We Insist 2025, drummer and bandleader Terri Lyne Carrington and vocalist Christie Dashiell’s update of Max Roach’s iconic civil rights album of the same name, was nominated in vocal jazz. More eyes were on Jesse Welles, the Arkansas indie roots-rocker who turned his talents toward “singing the news” in 2023, writing brief, highly topical songs almost daily and posting them across his socials. Nominated for four Grammys, Welles walked away with none.

Welles got famous in the obvious place to look for all kinds of topical songs in 2026: on social media, where the ability to create and distribute performances with a keystroke has fostered an ever-expanding agora. His rise came fast enough that some have doubted his motives — had he transformed himself from scruffy Southern bohemian to bandana-wearing dispatch rider only for his own benefit? Either way, his success represents what the mainstream music industry wants from protest music: an appealing and relatable conduit for ideas that many people long to hear expressed. I think Welles would be happy to admit that when it comes to getting his messages across, he’s a fortunate son — of John Fogerty, whose working-class anthems Welles greatly admires, and of Joe Strummer, whose sleeveless t-shirt look he sometimes adopts, and of Springsteen, an inevitable touchstone. Via that lineage, his presence connected the Grammys to the other big story in protest music last week, which featured a 20-time winner stepping out in the classic mode that has been designated for such gestures — the raucous, folk-inflected rock song.

Bruce Springsteen’s barn-burning broadside “Streets of Minneapolis,” had some chatterers wishing for a surprise Grammy appearance from the Boss. That was likely never a possibility, but to imagine it is exciting, not only because Springsteen’s song is uncompromisingly specific in addressing the violence that’s occurred in that city, but because it fits the narrow definition of protest songs most often welcomed into the mainstream. It’s an arena-ready polemic by a beloved rock star whose self-expression as a leftist fits the countercultural image set down by icons like Bob Dylan and his folk forefather Woody Guthrie. Its predecessors are obvious, starting with Dylan’s folk-based early songs and including festival favorites like Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young’s elegy for Kent State, “Ohio,” punk and hip-hop perennials like “Clampdown” by The Clash and Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” and more recent grenades like Rage Against the Machine’s “Killing in the Name” and Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright.” This list, and now Springsteen’s intervention, has defined the protest song in the rock- and hip-hop-era mainstream as a nearly-all-male endeavor drenched in swagger, indignation and unwavering belief in the right to speak out. For many music fans, songs like “Streets of Minneapolis” fulfill the mandate of protest music not only because of what they say, but because of who says it: the official rock and roll version of a rabble-rouser.

What I think is important to note, however, is neither Bruce Springsteen nor Bad Bunny nor Jesse Welles stand alone in creating songs that speak directly to our political moment. In fact, they are simply part of a wave that’s been building over the past decade, across genres, from Latin and indigenous hip hop to ambient music addressing the climate crisis to historically aware jazz to renewed old-school folk. Putting too much weight on a rock star’s gesture, no matter how stirring, creates a false hierarchy and threatens to narrow the definition of effective protest. I was reminded of this when I attended another awards ceremony last month in New Orleans. Folk Alliance International (full disclosure: until recently, I was on the FAI board, a volunteer position) focuses mostly on grassroots and independent artists, many of whom consider activism to be as crucial a part of their work as music-making. Its awards are bestowed in a hotel ballroom, not a basketball arena; honorees gather during a week of panels with titles like “Touring Activism in Today’s Climate” and “Motherhood in Music: Birds on a Wire.” At the ceremony, I watched as an array of highly engaged and committed protest singers took the podium, one after another, to accept their awards. They looked very different from what I would see on my television screen Sunday night.

FAI song of the year recipient Crys Matthews is a traditional folk singer expressing a queer point of view. Rising Tide winner Yasmin Williams, an amazing fingerpicking guitarist, gained national recognition when she turned a recent appearance at the Kennedy Center into a form of protest. Kyshona, who accepted the People’s Voice prize, is a singer-songwriter and country-soul diva who also is a music therapist working in prisons and in Nashville’s urban core. Carsie Blanton (who shared the artist of the year award with the trio I’m With Her, who weren’t in attendance, but did appear to accept two Grammys) is, according to many of her fans, “doing what people want Jesse Welles to do” — she’s a topical songwriter with a sound that blends jazz, folk and old-timey music and a life of activism that put her on a flotilla to Gaza last year and led to her imprisonment in Israel. These women received their awards from other artists including Leyla McCalla, whose music casts a wide net encompassing global rhythms and diasporic histories, and Ani DiFranco, who revitalized political folk for a new generation in the 1990s and has continually found new ways to expand its definition.

Certainly the efforts of such women have received attention; they were in New Orleans to pick up their flowers, after all. (Blanton refused to accept her award until the conference is made free for all attending musicians, citing the dire financial situation of most musicians and noting that “it’s very hard to embody revolutionary spirit when you’re 80,000 dollars in debt.”) My question is, would any of them have been included in a top five of activist musicians published in a major news outlet or celebrated at a televised awards show like the Grammys? Despite the fact that women have served as the faces of resistance in America from suffragism to civil rights and beyond, men’s voices, like their words, have historically been recognized as more representative. This is obviously partly because, in a sexist society, men have been elevated to leadership positions when women often have done the groundwork within various movements. It’s also connected to lingering ideas about what a creative voice should sound like: rebellious, singular, a little rough and a whole lot Romantic. The women who helped define protest music in this country, from Bernice Johnson Reagon, Mavis Staples and Joan Baez in the 1960s to the ones I’ve mentioned today, have sometimes been granted the spotlight — Baez was a bona-fide pop star — but were and are as likely to think and act in communion with others and make art that reflects the values they’ve developed as caregivers and organizers. Instead of standing alone, they’ve linked arms and shared the spotlight. And so, paradoxically, women’s songs have been judged as both too personal and too communal to be the definitive statements of protest.

Artists like Crys Matthews and Carsie Blanton also sometimes get overlooked within mainstream conversations because of the way they make and share their music. Both release conventional albums — here are their latest — but they’re also all over Instagram and other platforms where a particular song’s impact can be ephemeral or very niche, the online equivalent of a Greenwich Village hootenanny. In the fluid, interactive spaces where both grassroots music and activism have gravitated, an artist can nurture a fan base that’s also a political front; fans become comrades, and the line between star and admirer blurs. Institutions like the Grammys reinforce the separation between artist and audience by covering official success stories in glitter. Musicians who choose to operate outside the system may not enjoy that shine. That doesn’t mean their impact is less powerful. When asked what makes a political leader, the esteemed labor organizer Dolores Huerta famously said, “A leader is the person that does the work.” That kind of engagement happens in basements and on street corners more than at Hollywood galas.

While the throngs of marchers in Minneapolis and beyond make a great impression on distant phone screens, among those opposed to federal intervention it’s the day-to-day observers and neighbors who run communications on the ground, sustaining resistance. Some are musical allies whose protest music is not necessarily intended to resonate beyond the blocks where it is made. Groups like Brass Solidarity and Singing Resistance, who stand among activists on the streets and make music that both documents and feeds their actions, shape soundtracks to history that may never be fully recorded. Yet what they do may be the most vital liberatory gesture of all.

One person who seems to understand this is Bruce Springsteen. While any official statement from the Boss remains too overdetermined to purely serve social change, I’m impressed with his spontaneous broadside about the deaths of Alex Pretti and Renee Macklin Good. While “Streets of Minneapolis” is, at its core, nothing new from the man who gave us The Ghost of Tom Joad and We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, Springsteen shows he understands the moment when he gives over its arrangement to a mass of voices that’s redolent of the neighborhoods he honors in his song title. He lets his forward-pushing background singers lead him toward a vocal that’s increasingly loose, loud and tilting toward the communal. Kudos to America’s rock star for taking a back seat to the voice of a community. Doing so allows him to find where the real spirit of protest, and of survival, resides in 2026.

Alabama seek to bring back death penalty for child rape convictions

Alabama approved legislation Thursday to add rape and sexual torture of a child under 12 to the narrow list of crimes that could draw a death sentence.

What a crowded congressional primary in N.J. says about the state of Democrats

The contest is one of the first congressional primaries of the year where we will find out what issues are currently resonating with some Democratic voters. Here are some key things to know.

At NOCHI, students learn the art of making a Mardi Gras-worthy king cake

With Carnival in full swing, the New Orleans culinary school gave its students a crash course — and a rite of passage — in baking their first king cake.

The Winter Olympics in Italy were meant to be sustainable. Are they?

Italy's Winter Olympics promised sustainability. But in Cortina, environmentalists warn the Games could scar these mountains for decades.

Their film was shot in secret and smuggled out of Iran. It won an award at Sundance

Between war, protests and government crackdowns, the filmmakers raced to finish and smuggle their portrait of Tehran's underground arts scene to the prestigious film festival.

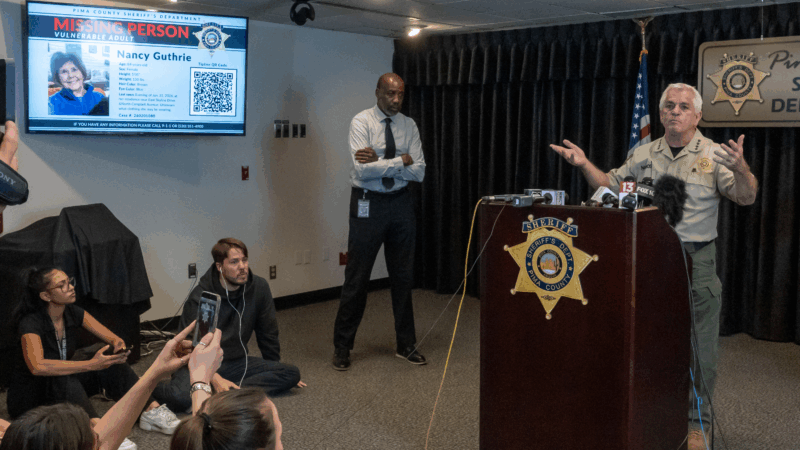

Day 5 of search for Nancy Guthrie: ‘We still believe Nancy is still out there’

The FBI is offering a reward of up to $50,000 for information leading to the recovery of Guthrie and/or the arrest and conviction of anyone involved in her disappearance.