Wes Anderson peers into the hollowness of extreme wealth in ‘The Phoenician Scheme’

It’s become customary to describe a new Wes Anderson movie as “more of the same,” but it says something about the sheer richness of his visual imagination that he can make two movies set in roughly the same era that look and feel nothing alike.

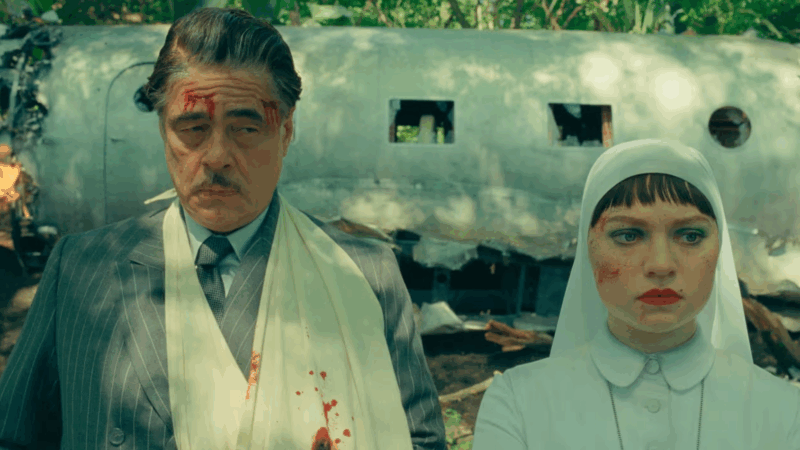

Anderson’s previous film, Asteroid City, was a gorgeous, warmly nostalgic ode to the American Southwest of the 1950s. His new movie, The Phoenician Scheme, takes place in the same decade, but it’s a chillier, more globe-trotting affair. It follows an obscenely wealthy businessman named Anatole “Zsa-zsa” Korda, played by an excellent Benicio Del Toro.

Korda is the latest of Anderson’s dashing scoundrels: the titan of industry as international man of mystery. He travels the world in private jets, making money, deals and enemies at every turn, and destabilizing governments and exploiting local workers along the way.

Now Korda wants to establish a lasting legacy. He plans to develop a massive infrastructure project in a place called Modern Greater Independent Phoenicia. To pull this off, Korda decides to reconcile with his estranged daughter, Liesl — she’s the oldest of his ten children — and make her his heir and partner.

Liesl, played by a terrific Mia Threapleton, isn’t sure she wants any part of it. Dumped in a convent when she was 5, she’s now a novitiate, and she scorns her father’s dishonest business practices. Also, there’s a rumor going around that, years ago, Korda killed Liesl’s mother.

Murderer or not, Korda fits snugly into Anderson’s ever-expanding gallery of bad dads, from Royal Tenenbaum to Steve Zissou. The Phoenician Scheme is a reconciliation story, and so Liesl reluctantly goes along with Korda’s harebrained plan, hoping she can do some good along the way. But it won’t be easy.

Much of the busy, preposterous plot follows Korda as he tries to get various business associates and family members to help finance his scheme. Anderson, who wrote the script with Roman Coppola, keeps updating us on how much each character has invested: At times, The Phoenician Scheme feels perilously close to math homework.

It’s not too hard to follow, though, especially compared with the more densely layered Asteroid City. The infrastructure deal is basically an excuse for the director to squeeze in as many of his favorite actors as possible. Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston play a pair of basketball-loving businessmen. Mathieu Amalric turns up as a nightclub owner, Jeffrey Wright as a sea captain. And there are other Anderson alums in the mix, too, like Bill Murray, Scarlett Johansson, Richard Ayoade and Hope Davis.

The first-timers, though, make the strongest impressions. Riz Ahmed plays an endearing Phoenician prince, and Michael Cera is delightful as a nerdy Norwegian entomologist named Bjorn. The most moving performance comes from Threapleton. Her Liesl has the radiant self-possession of the French icon Anna Karina, who gave one of the all-time great nun performances in Jacques Rivette’s 1966 classic, La Religieuse.

Although Anderson’s films are often suffused with themes of spirituality, morality and grace, he seldom engages the subject of religion as directly as he does here. In a way, the father-daughter relationship is a metaphor for God and money, in which Korda’s endless pursuit of riches keeps bumping up against Liesl’s strong sense of faith and social justice.

The Phoenician Scheme may present itself as a fabulous piece of stylized escapism, but it’s hard to watch it and not think about the oligarchs of today. Anderson’s style is often described as whimsical, but here, he’s made a movie about the literal whims of tycoons. The film has his signature visual touches, full of symmetrical compositions and exquisite textures and details, but there’s an uninviting coldness to the backdrops themselves: a rich man’s fortress, a half-built railway tunnel, a fancy but dim nightclub. It’s as if we’re seeing the hollowness of extreme wealth.

In some ways, this is one of Anderson’s darker, angrier, more violent films. One of the first things we see is a man being blown in half by a bomb intended for Korda, who’s the target of multiple assassination attempts. Whenever he’s in danger, Korda says, “Myself, I feel very safe,” which is hardly reassuring to those around him.

The Phoenician Scheme is well aware that men like Korda make life worse for everyone else, which is why I’m still puzzling over the movie’s happy ending, which, at the last minute, engineers a fateful change of heart. The conclusion Anderson leaves us with could be read either hopefully or cynically: for the “Zsa-zsa” Kordas of the world to do the right thing might well require an act of God.

The U.S. unexpectedly loses 92,000 jobs, adding to worries about the economy

The job market showed further signs of weakness last month as employers cut 92,000 jobs. The unemployment rate inched up to 4.4%, from 4.3% in January.

Iran retaliates after Israel strikes Beirut and Tehran as war enters Day 7

Iran fired missiles toward Israel Friday, Israeli officials said, after Israel launched fresh strikes on Tehran and hit Beirut's southern suburbs overnight.

Bernard LaFayette, Selma voting rights organizer, dies at 85

LaFayette laid the foundations of the Selma, Alabama, campaign that culminated in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. He was a Freedom Rider and helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

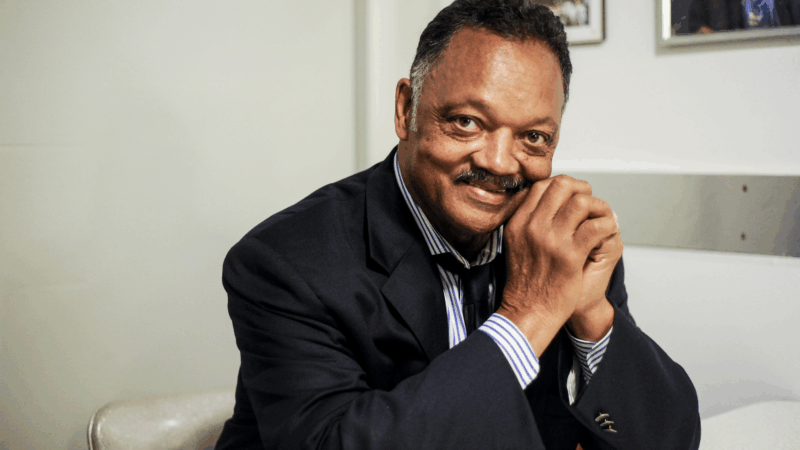

Homegoing service will celebrate civil rights leader Jesse Jackson in Chicago

Chicago native Jennifer Hudson is among the singers performing at a memorial for the civil rights leader who died last month. Former presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden will attend.

Was that really Jim Carrey? The internet had thoughts but the quiz has answers

Plus: Primates of all varieties!

The Kalshi and Polymarket CEO feud: They hate each other

The 20-something billionaires who run Kalshi and Polymarket are battling it out to be the top prediction market company. Observers and former insiders say the feud is just heating up.