Venezuela’s exiles in Chile caught between hope and uncertainty

SANTIAGO, Chile — Early last Saturday morning, Chile’s capital awoke to the sound of jubilant cheers echoing between the tower blocks.

News had filtered through from Caracas of the U.S. operation to seize President Nicolás Maduro, and Chile’s sizable Venezuelan diaspora could barely contain its joy.

More than 1,000 people gathered in Parque Almagro in Santiago to embrace one another, cheer, chant and weep.

“I was in the park with them all day,” said Mary Montesinos, 49, the Chile representative of Voluntad Popular, one of Venezuela’s major opposition parties.

“The topic of conversation was that we’re all going to go home, the regime will fall and we will get our democracy back.”

But, like many, Montesinos is keen to urge caution. “They’ve captured Maduro, but the regime hasn’t fallen,” she said. “They’ve been building it for 25 years, it’ll take a long time to disassemble.”

Amid one of Latin America’s worst ever refugee crises, the United Nations Refugee Agency estimates that as much as 23 percent of Venezuela’s population has fled the country as the economic crisis deepened. At the end of last year, as many as 2,000 people were still leaving every day.

Chile has received many of these migrants.

Montesinos arrived in 2003 with her Chilean husband when there were almost no Venezuelans living in the country. She remembers early meet-ups for the diaspora were largely attended by Chileans who had grown up in Venezuela, and they would make typical Venezuelan dishes using whichever replacement ingredients they could find.

Now, shops up and down the country sell queso llanero, a crumbly white cheese, and Venezuelan brands of cornflour. Tiny bars in desert towns sell bottled Venezuelan drinks, and you can even find arepas and tequeños in blustery Punta Arenas, Chile’s southernmost city just above the Antarctic circle.

Several waves of migration have brought Venezuelans down to the south of the continent, with many arriving via other Latin American nations in search of employment and opportunities. During the coronavirus pandemic, with borders closed, many arrived illegally on foot through the desert, too.

In Chile’s 2024 census, Venezuelans were comfortably the largest group of foreigners in the country among its 18.5 million population. It registered 669,000 Venezuelans in Chile, far more than the second-largest diaspora: 233,000 Peruvians. The majority are young, with only 5% of the Venezuelan population in Chile older than 45.

But there has been significant pushback from Chileans with the new arrivals.

“When they report crimes on the news, they only say the nationality of the perpetrator if they’re foreign, installing a negative perception around Venezuelan migration,” said Montesinos.

Chile’s president-elect, far-right José Antonio Kast, stormed to victory in December’s elections by linking a wave of illegal migration to a sense of public insecurity and fears over organised crime. He made a habit of threatening illegal migrants at his public rallies by counting down the days for them to leave Chile before his inauguration on 11 March.

An estimated 334,000 Venezuelans are living illegally in Chile. Kast has mooted detention facilities, border walls and ditches to halt illegal migration; and aggressive policies to pursue, detain and deport illegal migrants.

Kast enthusiastically welcomed the U.S. intervention in Chile, describing the operation as “great news.”

Outgoing leftist President Gabriel Boric was more circumspect: “Today it’s Venezuela, tomorrow it could be any other [country].”

Roberto Becerra, 43, arrived in Chile in 2017, fearing for his safety in Venezuela due to his political activities.

He helped organise three voting stations in Santiago for the 2024 presidential elections in Venezuela, in which President Maduro claimed victory despite international observers widely asserting that the opposition had won.

“What we can do from Chile as members of political parties is make what is happening in Venezuela visible,” he said.

“We are the voice of those who cannot speak up, because look what has happened in Venezuela – nobody has been able to say anything, whereas in the rest of the world we have been out in the streets celebrating.”

But while uncertainty remains for many, nostalgia for Venezuela has got many in the diaspora in Chile dreaming of a return home.

Montesinos says that, under the right circumstances, she would return to help rebuild the country, “If there was a call to return [to Venezuela] to help rebuild, I would go,” she said.

“To be part of that story would be really inspiring.”

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

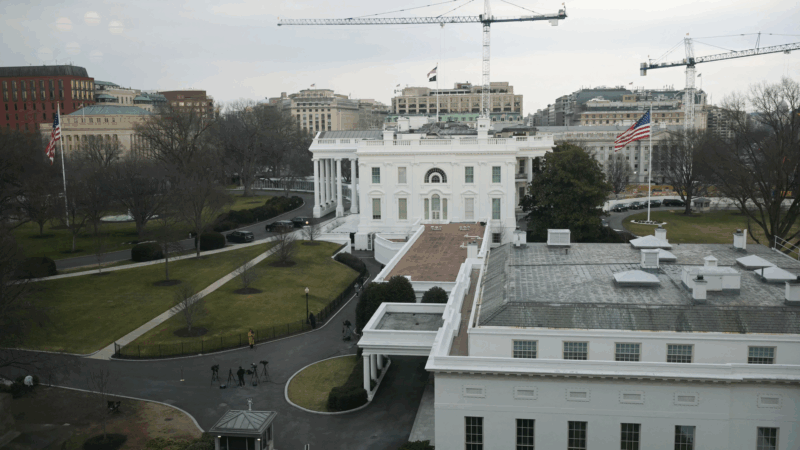

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

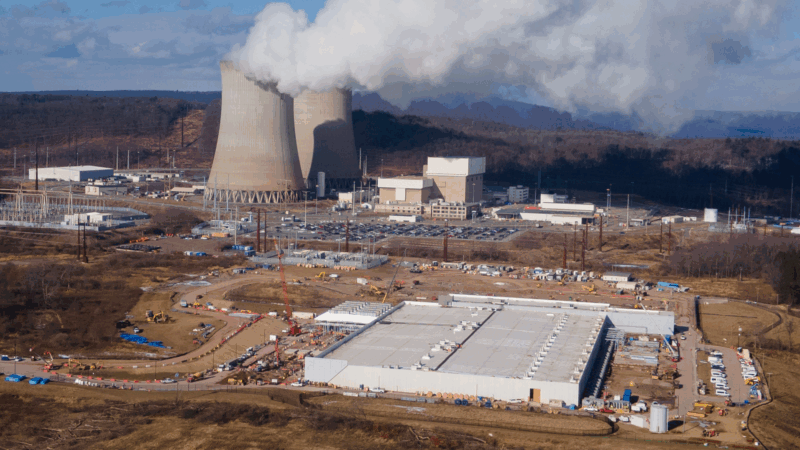

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.