Uruguay’s ex-President José Mujica, nicknamed ‘world’s poorest president,’ dies at 89

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — José Mujica, a former guerrilla fighter who became a symbol of national reconciliation after he disarmed and was elected president of Uruguay, and whose frugal living earned him the nickname “the world’s poorest president,” has died. He was 89.

His death was announced Tuesday by Uruguayan President Yamandú Orsi. “It is with profound sorrow that we announce the passing of our friend, Pepe Mujica. President, activist, leader and guide. We’re going to miss you very much, dear old man. Thank you for everything you gave us and for your profound love for your people,” Orsi wrote on social media.

Mujica had said in January that his esophageal cancer had spread to his liver and that he would forgo further medical treatment.

Mujica, Uruguay’s president from 2010 to 2015, was among of a batch of left-leaning politicians — often called the “pink tide” — who came to power in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and elsewhere in Latin America in the early part of this century.

He oversaw an economic boom, a surge in foreign investment and a reduction in poverty in the small South American nation of more than 3 million people, while avoiding corruption scandals. His progressive policies included legalizing abortion, marijuana and same-sex marriage, as well as the resettlement of war refugees from Afghanistan.

“It was a very successful presidency,” said Pablo Brum, who interviewed Mujica for his book The Robin Hood Guerrillas. “In those years, he became a superstar. The Economist named Uruguay the first-ever ‘country of the year.’ There was a Uruguay mania. He put Uruguay on the map for a lot of people.”

Mujica, widely known by his nickname, “Pepe,” was 8 when his father died, leaving him to be raised by his flower-seller mother. Outraged by Uruguay’s gap between rich and poor and fascinated by the 1959 Cuban Revolution, he sought political change through guerrilla warfare.

“By the early 1960s, Mujica was among many young people who found armed struggle anywhere from desirable to inevitable,” Brum said. “So the notion of, like Che Guevara, picking up a gun and effecting social change and political change — right here, right now — he fell into that.”

Mujica joined the National Liberation Movement, a rebel group widely known as the Tupamaros. Its members carried out bombings, bank robberies and kidnappings and in 1969 briefly occupied the Uruguayan town of Pando. But the Tupamaros never came close to seizing power, and in 1970 Mujica was captured after a shoot-out with police in which he was badly wounded.

After recovering, Mujica took part in an audacious jailbreak. His fellow Tupamaros inmates built a 130-foot-long tunnel to a house across the street from the prison, which allowed Mujica and 105 other rebels to escape.

But most were quickly rounded up. Mujica was beaten and tortured, and he spent so much time in solitary confinement that he befriended ants, frogs and rats.

Still, prison gave him time to reflect — and to realize the rebels were doing more harm than good. Indeed, rebel violence and chaos weakened Uruguay’s civilian government and helped pave the way for a 1973 coup that plunged the country into military dictatorship.

“What we didn’t realize was that when you play with fire, you may unleash forces that you can’t control,” Mujica told the Uruguayan newspaper El País in 2020.

Mujica “spent those years [in prison] trying to educate himself, trying to understand the political system, the world, and also to understand who he was,” says Mauricio Rabuffetti, a Uruguayan journalist who wrote a biography of Mujica.

Mujica was released in 1985. By that time, Uruguay’s dictatorship had given way to a democratic government, and Mujica eventually embraced electoral politics.

In doing so, says Rabuffetti, “he helped ensure that Uruguay would [become] a stable country with strong institutions. He understood that Uruguayans didn’t want a fight but, rather, peace and stability.”

This transition was helped by Mujica’s sense of humor, folksy manner and rustic lifestyle, which made him a darling of the news media. Short, gray-haired and often looking disheveled, he would give interviews while sipping maté, an herbal drink, at his tiny farmhouse outside the capital, Montevideo, where he and his wife grew flowers.

“It’s a very simple house made of bricks, or concrete blocks,” Rabuffetti said. “The roof is made of sheet metal. There is a small kitchen, a bedroom and a bathroom, and you can see everything from the front door.”

For many average Uruguayans, who were fed up with pompous politicians and government corruption, Mujica seemed more like one of them. He was elected to parliament in 1994, was named minister of livestock, agriculture and fisheries in 2005 and, four years later, won the presidency.

Yet even at the moment of his greatest triumph on election night in 2009, the then-74-year-old president-elect refused to gloat. Instead, he apologized to the losing candidate for having used some harsh rhetoric during the campaign and pledged: “Tomorrow, we shall walk together.”

High office didn’t change Mujica very much. He eschewed the official residence in Montevideo for his ramshackle flower farm. Rather than a presidential motorcade, he often drove his 1987 Volkswagen Beetle to work. He dressed casually and donated nearly all his salary to charity.

His austerity was no gimmick. Mujica thought politicians should live like average folks and frequently declared that the well-off in the world must get by on less. At the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 2012, he bluntly told delegates: “Hyperconsumerism is what is destroying the planet.”

In his twilight years, as the world became more polarized, Mujica looked back on his own extremist past with chagrin and endorsed moderation.

“In my own garden, I no longer plant the seeds of hatred,” he said in a 2020 speech announcing his retirement from active politics. “Life has taught me a hard lesson … that hatred just makes us all more stupid.”

A new Nepali party, led by an ex-rapper, is set for a landslide win in parliamentary election

A Nepali political party led by an ex-rapper is set for a landslide victory in the country's first parliamentary election since Gen Z protests ousted the old leadership that has ruled the Himalayan nation for decades.

U.S. Judge says Kari Lake broke law in overseeing Voice of America

He declared all of Lake's actions over the past year to be null and void, including the layoffs of more than 1,000 journalists and staffers.

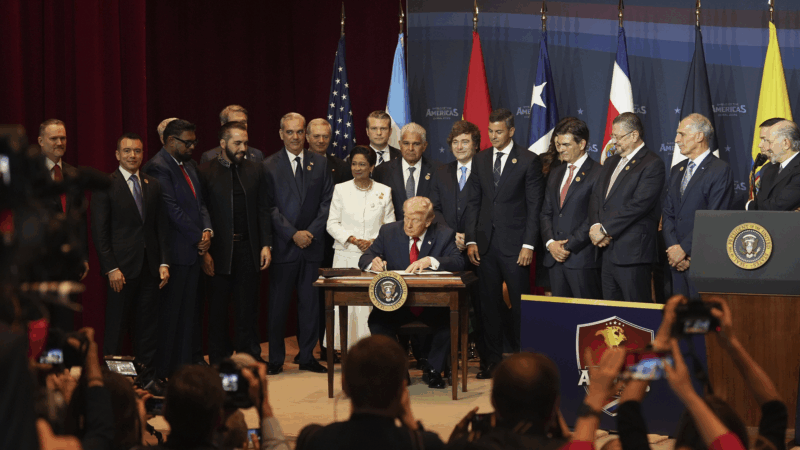

Trump vows to ‘take care of Cuba,’ praises Venezuela cooperation at summit

Trump made the promise in front of an assembled meeting of Latin American leaders.

British Columbia to make daylight saving time permanent

The Canadian province is permanently ending the biannual time shifts for more light at the day's end. But research shows daylight saving increases health risks.

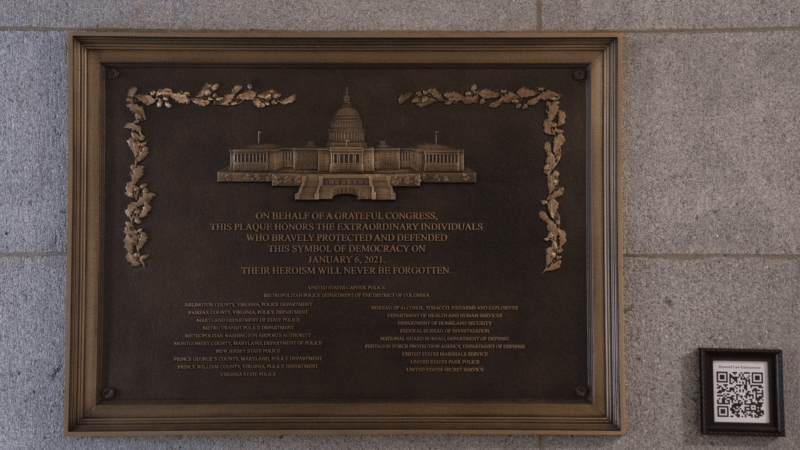

Jan. 6 plaque honoring police officers is now displayed at the Capitol after a 3-year delay

Visitors to the Capitol in Washington now have a visible reminder of the siege there on Jan. 6, 2021, and the officers who fought and were injured that day.

Authorities searching debris after suspected tornadoes kill 6 in Michigan, Oklahoma

A 12-year-old boy is reported to be among the dead following powerful storms that stretched across the middle of the country.