This office was meant to bridge divides in government. Now it’s empty

The Joint Office of Energy and Technology, an unusual federal office that was established by a bipartisan act of Congress in 2021, has been so deeply affected by efforts to shrink the government that it now appears to exist primarily on paper.

The Joint Office, as it was commonly known, was set up as a bridge between the Department of Transportation and the Department of Energy. Their area of overlap: electric vehicles. One of the office’s main tasks was to support the rollout of federally funded EV chargers. EVs were a top priority for the Biden administration — and a top target for rollbacks by the Trump administration.

But while the Trump administration has deliberately undone or reversed many of Biden’s EV policies, the Joint Office does not appear to have been singled out for dismantling: There were no executive orders against it, and no indication of office-specific layoffs. Instead, the government-wide effort to slash jobs and the freezing of work related to climate change seems to have combined to push employees out the door.

At its peak, the office employed around 50 people, including federal employees as well as contractors and fellows. (The staffing numbers varied because some people split their time between different agencies, or were on loan from elsewhere in the government.)

But no full-time federal employees remain after the most recent round of deferred resignations, when people were encouraged to resign in exchange for getting months’ worth of pay. That’s according to several people who recently departed the office. (They asked NPR not to use their names out of concern that their severance or former projects could be retaliated against if they spoke publicly.)

“The Joint Office was not necessarily a target,” says Gabe Klein, the founding director of the Joint Office who stepped down in February. “It was going to be caught in the crossfire and it was going to diminish on its own.”

An experiment in breaking down silos

Klein calls the Joint Office a “start-up within the government,” a nod to its recent invention and its unusual nature.

The law that established it, called the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, designated billions of dollars for EV chargers, particularly along highways.

Highways are the domain of the Department of Transportation. Electricity, though — that’s the Department of Energy.

Those two agencies “never really talked to each other,” says Phil Jones, the executive director of the Alliance for Transportation Electrification and a long-time advocate for EV policies. “They certainly didn’t plan together.”

Congress, though, wanted collaboration. The Joint Office, Klein says, was the first of its kind at the federal level.

For four years, the team worked on EV charger reliability, research and planning. Then President Trump was re-elected.

A slow diminishing

It was no secret that Trump was keen to reverse Biden’s EV policies — although his embrace of Elon Musk, the CEO of an EV company, was a wild card for people trying to predict how the administration would ultimately approach EVs and charging infrastructure.

Early on, Trump initiated the process of rewriting regulations that promote EVs, and froze the federal funding for many chargers. But the former staffers at the Joint Office say they were holding out hope they could continue doing at least some of their work, which touched everything from cybersecurity to technical standards.

“We knew they were going to be coming for us, but we thought our statutory existence would help us,” one of the former staffers said, referring to how Congress had explicitly created the team and given them a mission.

But while there was no explicit campaign against the office, it seems to have instead died a — perhaps accidental — death by attrition.

In February, like other federal employees, everyone in the Joint Office was invited to resign and keep their pay through September, and some did. Probationary employees were also cut, which hit the young team hard, the former staffers say.

Meanwhile, many of the team’s projects — or the funding for them — were frozen or got stuck in limbo, especially anything related to climate change. That affected contractors and researchers, who had to be put on other work, as well as staffers.

“You are pretty much staring at a computer and not doing work,” says Klein. “And for people that are motivated, that’s very demotivating.”

There were also return-to-office mandates that affected some staff, who had been hired to work remotely, the former staffers say. Some people had concerns about future layoffs or reorganizations, or feared that if they didn’t resign they’d ultimately be laid off. Add it all up, and when the second invitation to resign came in April, people who had previously decided to stay reconsidered.

By that point, fewer than a dozen full-time federal staffers were left, according to those former staffers. All of them now appear to have resigned. In most cases, their final day was last Friday.

The Joint Office still has a website, but it no longer lists any leaders or staff.

Frustration over feeling like their work was being impeded was a theme, from Klein as well as other members of the office.

“I, personally, would like to do something that makes a difference over the next several years,” says Steve Lommele, who recently left his role as communications director for the Joint Office. He mentioned global competitiveness — Chinese EV innovations have raised concerns about whether U.S. companies can compete — and supporting the buildout of a national EV charging system to make driving one a more viable choice.

That’s what the Joint Office was built to do. But as he pondered leaving his role, he thought: “I don’t know if I’ll have the ability to do that in my role in the federal government.”

The former Joint Office staffers who spoke to NPR say that some fellows and contractors will keep working on Joint Office projects, but at one agency or the other, rather than in the hybrid space that Congress had established.

Asked about the changes, the Department of Energy provided a statement that read in part: “The Department is conducting a department-wide review to ensure all activities follow the law, comply with applicable court orders and align with the Trump administration’s priorities.”

The Department of Transportation did not return requests for comment.

A “bridge” that’s being dismantled

The Joint Office was tasked with supporting the buildout of a nationwide EV charging system. Only a fraction of that system was going to be federally funded, and the office worked on making the whole network more reliable, with a focus on the technical standards and shared protocols that reduce glitches when cars and chargers interact. The goal? For charging to work more consistently and be less frustrating for drivers, no matter which company’s technology they were using.

A lot of that involved bringing people together to talk more effectively.

One consortium launched by the Joint Office pulled together auto companies and charging companies, hardware experts and software experts, to hash out roadblocks that were making so many EV chargers unreliable. The Joint Office’s technical assistance program brought people from state departments of transportation together with those from utility commissions and energy offices to, as Jones put it, “work on tough subjects and try to try to get things done.”

Some of that work has been ongoing under the Trump administration, while other Joint Office work has been disrupted. Most notably, the Joint Office provided research and support for the federally funded charger program, called the NEVI program. That was a complicated program, with federal money and state planning and implementation, which was widely criticized for being slow to build chargers. The funding is currently frozen, with an uncertain fate.

One departing staff member argued that researchers and contractors can still carry on much of the Joint Office’s work within the federal government, at either DOE or DOT.

Another argued that the work will need to be picked up by the private sector instead: “We had the baton and now we need to pass it back.”

Either way, both argued, someone needs to be pulling together researchers and companies, business rivals and allies, state and federal governments, and engineers with different backgrounds to hash out the details of building effective EV chargers.

Nick Nigro runs Atlas Public Policy, a policy and data research firm. He says the Joint Office was a valuable bridge, and that if it has truly disappeared as a stand-alone office, it would be a real loss.

But, he said, “we made progress on these kinds of issues without the Joint Office. And we will, whether or not it exists. It’s just — it might go slower and it might be more cost ineffective. Which is sort of ironic, given the current goals of the administration.”

Transcript:

MARY LOUISE KELLY, HOST:

A few years ago, Congress had an idea – a special office connecting two federal agencies that both work on electric vehicles. But this startup within the government has become a casualty – possibly an accidental casualty – of the push to shrink the government. NPR’s Camila Domonoske reports on how that office has become a ghost ship.

CAMILA DOMONOSKE, BYLINE: When Congress passed the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021, it designated billions for electric vehicle chargers, especially along highways. The Department of Transportation handles all things highway. The Department of Energy knows about all things electricity. And those two?

PHIL JONES: They never really talked to each other. They certainly didn’t plan together.

DOMONOSKE: That’s Phil Jones, who has spent years advocating for EV policies. Congress wanted them to plan together, so this law invented something new, a Joint Office of Energy and Transportation.

GABE KLEIN: This was the first joint office that had ever been created at the federal level to span multiple agencies.

DOMONOSKE: That’s Gabe Klein, the founding director. Klein left in February, and that wasn’t a surprise. New administration, new leadership – but he thought the team would continue. After all, the work was mandated by Congress. There were once close to 50 people at the Joint Office, but the cuts this year to probationary staff hit hard. As a newer office, there were lots of recent hires. The government also invited people to resign but keep their pay through September. At first, a lot of people stuck around, but projects were in limbo. Across the government, people who work on climate-related topics had their work frozen, affecting contractors and staffers.

KLEIN: You are pretty much staring at a computer and not doing work. And for people that are motivated, that’s very demotivating.

DOMONOSKE: There were return-to-office mandates, new fears of future layoffs and then, in April, a second invitation to resign. It hit different. After that, Klein says…

KLEIN: I’m not sure we’ll have any full-time people left in the Joint Office.

DOMONOSKE: I talked with several people who’ve recently left the Joint Office, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they’re worried about retaliation related to their severance or former projects. They said that to their knowledge, every full-time federal employee in the office is leaving. In most cases, their last day was last Friday.

The Joint Office still has a website, but it no longer lists any leaders or staff. And here’s the twist. Despite all the actions this administration has aimed at EVs, people I spoke to don’t think this was planned. There was no executive order aimed at them, and it wasn’t like the new administration laid the whole team off. Here’s Klein.

KLEIN: The Joint Office was not necessarily a target.

DOMONOSKE: Asked about the changes, the Department of Energy said in a statement it was, quote, “conducting a department-wide review” to ensure activities are legal and, quote, “align with the Trump administration’s priorities.” The Department of Transportation did not return requests for comment.

The people I’ve talked to say that some fellows and contractors will keep working on Joint Office projects but at one agency or the other, rather than living in this special space between the two. The Joint Office got people to talk to each other – two different federal agencies, yes, but also the Feds and the states, academics and industry, auto companies and charging companies. They worked out some technical details to make charging more reliable. So when you plug in any EV at any charger…

All right.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHARGER CLICKING)

DOMONOSKE: …Especially if the car and charger are from two different companies…

(SOUNDBITE OF BEEP)

DOMONOSKE: …There’s a higher chance 15 seconds later, you’ll be saying this…

Charging started.

…Instead of saying something we can’t air on NPR. Nick Nigro runs Atlas Public Policy, a policy and data research firm. He says the Joint Office’s role bridging divides was really valuable. Without the Joint Office, he says, that work will still happen in the private sector.

NICK NIGRO: It’s just it might go slower, and it might be more cost-ineffective, which is sort of ironic, given the current goals of the administration.

DOMONOSKE: As EV infrastructure grows, energy and transportation experts have to work together somewhere. It just might not be in the home Congress made for them. Camila Domonoske, NPR News.

Voting nears to a close in Texas primary that may be crucial to control of the Senate

The GOP and Democratic primaries mark a potential litmus test for what direction base voters want their parties to go ahead of midterm elections this fall that will determine power in Congress.

Pregnant migrant girls are being sent to a Texas shelter flagged as medically risky

Government officials and advocates for the children worry the goal is to concentrate them in Texas, where abortion is banned.

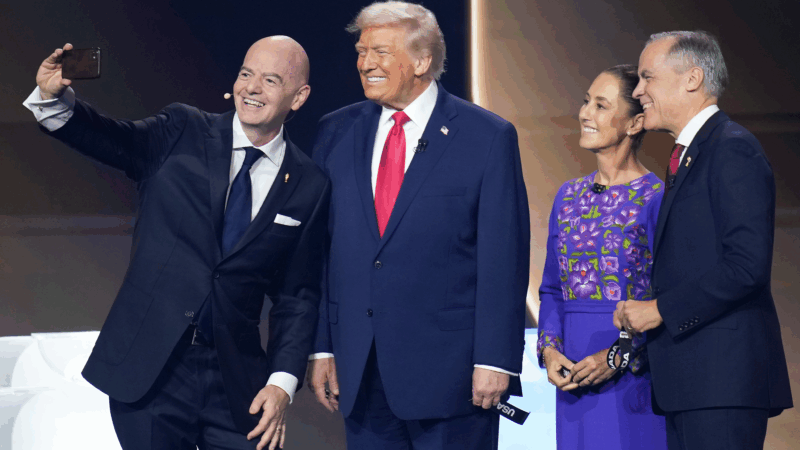

The 2026 World Cup faces big challenges with only 100 days to go

Will Iran compete? Will violence in Mexico flare up? And what about funding for host cities in the U.S.? With only 100 days left before it beings, the 2026 World Cup in North America is facing a lot of uncertainty.

A glimpse of Iran, through the eyes of its artists and journalists

Understanding one of the world's oldest civilizations can't be achieved through a single film or book. But recent works of literature, journalism, music and film by Iranians are a powerful starting point.

Mitski comes undone

She may be indie rock's queen of precisely rendered emotion, but on Mitski's latest album, Nothing's About to Happen to Me, warped perspectives, questionable motives and possible hauntings abound.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.