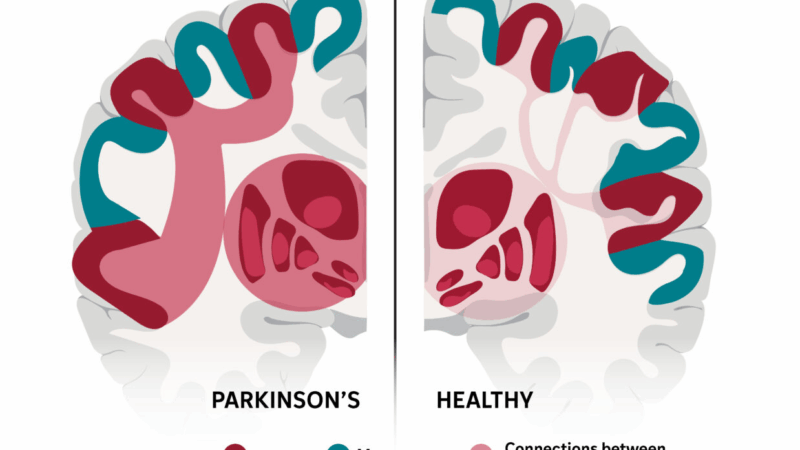

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson’s disease does more than cause tremor and trouble walking. It can also affect sleep, smell, digestion and even thinking.

That may be because the disease disrupts communication in a brain network that links the body and mind, a team reports in the journal Nature.

“It almost feels like a tunnel is jammed, so no traffic can go normally,” says Hesheng Liu, a brain scientist at Changping Laboratory and Peking University in Beijing and an author of the study.

The finding fits nicely with growing evidence that Parkinson’s is a network disorder, rather than one limited to brain areas that control specific movements, says Peter Strick, a professor and chair of neurobiology at the University of Pittsburgh who was not involved in the study.

Other degenerative brain diseases affect other brain networks in different ways. Alzheimer’s, for example, tends to reduce connectivity in the default mode network, which supports memory and sense of self. ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) primarily damages the motor system network, which controls movement.

Understanding the network affected by Parkinson’s, which affects about 1 million people in the United States, could change the way doctors treat the disease.

A mystery solved?

People with Parkinson’s often have symptoms that vary in ways that are hard to explain.

For example, someone who usually is unable to stand may suddenly leap when faced with an emergency. And Parkinson’s patients who can still walk may freeze if they try to carry on a conversation.

“So you know that their movement problems [are] not simply related to their motor circuits,” Liu says, but also to circuits involved in thinking and emotion.

For decades, scientists struggled to explain how these circuits are linked.

Then in 2023, a team led by researchers at WashU Medicine in St. Louis discovered a brain network that does seem to connect movement and thinking.

They named it the somato-cognitive action network, or SCAN. And Liu’s team thought it might explain some of the odd symptoms seen in Parkinson’s.

So they used MRI data on more than 800 brains to compare the SCAN networks in healthy people with those in Parkinson’s patients.

The team found that patients had abnormally strong connections between the SCAN network and brain areas known to be affected by their disease.

Instead of making communication better, Liu says, those strong connections were causing a traffic jam that kept signals from getting through.

Treating the network

Next, Liu’s team looked to see what happened to the SCAN network when people with Parkinson’s got deep brain stimulation — a treatment that delivers pulses of electricity to areas affected by the disease.

“When the stimulator is turned on, the connectivity was immediately lowered,” Liu says, allowing brain traffic to flow normally again.

To see how other treatments altered the SCAN network, the team studied patients receiving the drug levodopa, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and focused ultrasound stimulation.

“All these effective treatments are actually acting on this same circuitry,” Liu says, “and the effect is, remarkably, identical.”

The finding is just the latest to show how the conventional wisdom about Parkinson’s has changed.

“In the past, people thought of Parkinson’s disease as the classic movement disorder,” Strick says. “But it’s clear now that multiple systems are involved.”

People with Parkinson’s often describe symptoms that go far beyond problems with voluntary movement, such as tremor, slurred speech and a shuffling gait.

Lesser known symptoms include chronic constipation, a reduced sense of smell, sleep disorders, memory lapses and fatigue — all of which involve brain systems with no direct link to voluntary movement.

Not a drunk

This sometimes unpredictable mix of symptoms can be misinterpreted in a way that feels stigmatizing to patients, doctors say.

Strick recalls one man whose early symptoms included a sudden drop in blood pressure when he stood up.

“He would fall down, unexplainably, and people thought he was a drunk,” Strick says, adding that the man was actually pleased when he got a medical diagnosis that explained his behavior.

The new study appears to explain odd symptoms like that, Strick says. They’re occurring, he says, because the SCAN network includes brain areas that normally control involuntary functions, like heart rate, digestion and blood pressure.

SCAN areas also include those that affect REM sleep, and certain types of memory and thinking.

Current treatments for Parkinson’s don’t fix these non-motor problems, Liu says. But future ones might, he says, by targeting overlooked areas in the brain’s SCAN network.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Parkinson’s disease does more than cause tremors and trouble walking. It can also affect sleep, smell, digestion and even thinking. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports on new research suggesting that’s because the disease disrupts a brain network that links the mind and body.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: People with Parkinson’s often have symptoms that are hard to explain, says Hesheng Liu of Changping Laboratory in Beijing. For example, he says patients may be able to walk most of the time but freeze up when a path becomes narrow or someone asks them a question.

HESHENG LIU: So you know that their movement problems is not simply related to their motor circuits. It’s also related to their cognitive circuits.

HAMILTON: But it hasn’t been clear why. Then several years ago, a team led by researchers at Washington University in Saint Louis discovered a brain network that seems to connect movement and thinking. They named it the somato-cognitive action network – or SCAN. And Liu’s team thought it might explain some of the odd symptoms of Parkinson’s. So they used MRI data on more than 800 brains to compare the SCAN networks in healthy people with those in people with Parkinson’s.

LIU: In the patients, the connectivity in this SCAN network is abnormally high.

HAMILTON: The network linking thoughts and actions has too many connections. Liu says this causes signals to get stuck.

LIU: It almost feels like a tunnel is jammed, so no traffic can go normally.

HAMILTON: Next, Liu’s team looked to see what happened to the SCAN network when people with Parkinson’s got deep brain stimulation, a treatment that delivers pulses of electricity to areas affected by the disease.

LIU: When the stimulator is turned on, the connectivity was immediately lowered.

HAMILTON: Allowing brain traffic to flow normally again. Liu wanted to know how other treatments altered the SCAN network. So his team studied patients being treated with the drug levodopa, magnetic stimulation and focused ultrasound.

LIU: All these effective treatments are actually acting on this same circuitry, and the effect is remarkably identical.

HAMILTON: And treatments seemed to be more effective when they focused on areas that are part of the SCAN network. The research appears in the journal Nature. Peter Strick, a neurobiologist at the University of Pittsburgh, says it reflects a better scientific understanding of a disease that affects about 1 million Americans.

PETER STRICK: In the past, people thought of Parkinson’s disease as the classic movement disorder. But it’s clear now that multiple systems are involved in Parkinson’s disease.

HAMILTON: Stick says patients often describe symptoms that go beyond tremor, slurred speech and a shuffling gait. These include chronic constipation, a reduced sense of smell, sleep disorders, memory lapses and fatigue, all of which involve brain systems with no direct link to voluntary movement. Strick recalls one man whose early symptoms included a drop in blood pressure when he stood up.

STRICK: He would fall down unexplainably, and people thought he was a drunk. There’s such a stigma attached to that that when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, he said, there, I’m not a drunk.

HAMILTON: Strick says the new study appears to explain symptoms like that. They occur because the SCAN network includes brain areas that control involuntary functions like heart rate, digestion and blood pressure.

STRICK: You don’t say, well, OK, I’m going to stand up now, and so I’ve got to increase the blood flow in my brain. This is sort of the housekeeping that’s taken care of for you.

HAMILTON: If your brain is healthy. Strick says current treatments for Parkinson’s don’t fix problems like that. But future ones might, he says, by targeting overlooked areas in the brain SCAN network.

Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

Voting nears to a close in Texas primary that may be crucial to control of the Senate

The GOP and Democratic primaries mark a potential litmus test for what direction base voters want their parties to go ahead of midterm elections this fall that will determine power in Congress.

Pregnant migrant girls are being sent to a Texas shelter flagged as medically risky

Government officials and advocates for the children worry the goal is to concentrate them in Texas, where abortion is banned.

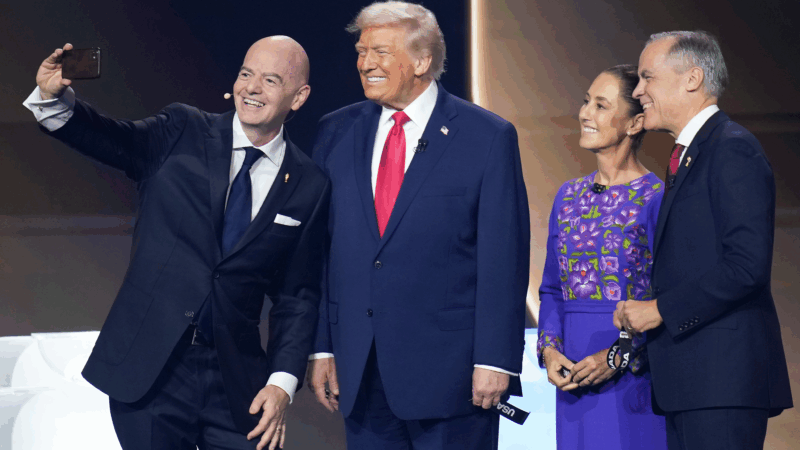

The 2026 World Cup faces big challenges with only 100 days to go

Will Iran compete? Will violence in Mexico flare up? And what about funding for host cities in the U.S.? With only 100 days left before it beings, the 2026 World Cup in North America is facing a lot of uncertainty.

A glimpse of Iran, through the eyes of its artists and journalists

Understanding one of the world's oldest civilizations can't be achieved through a single film or book. But recent works of literature, journalism, music and film by Iranians are a powerful starting point.

Mitski comes undone

She may be indie rock's queen of precisely rendered emotion, but on Mitski's latest album, Nothing's About to Happen to Me, warped perspectives, questionable motives and possible hauntings abound.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.