There’s an internet blackout in Iran. How are videos and images getting out?

Iranian authorities have implemented a near-total shutdown of the internet in a crackdown on widespread anti-government protests, but a sliver of the population is keeping in touch with the outside world by satellite.

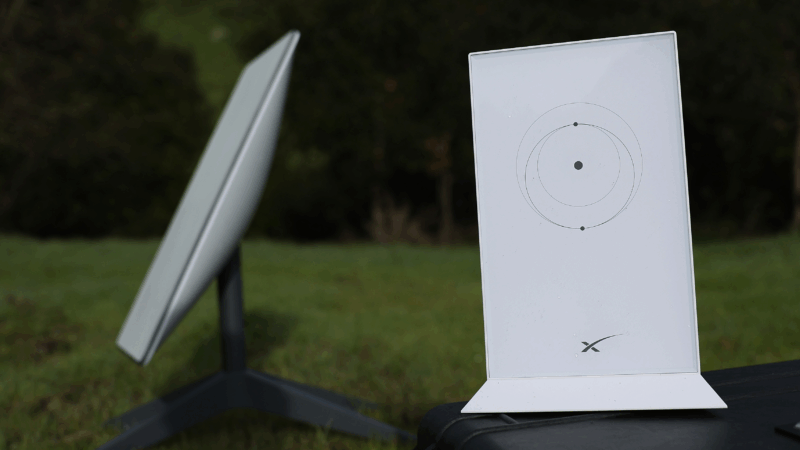

Starlink, a division of Elon Musk’s rocket company SpaceX, is playing an outsized — and in the eyes of overseas activists, crucial — role in connecting Iran with the rest of the world as the country’s leadership turns to force to try to quash the protests.

Starlink provides high-speed internet access, and can be used in many places where internet connections are hard to get, including rural areas and at sea. It has also been used in conflict zones before. After Russia’s invasion, SpaceX made Starlink available in Ukraine, and it quickly became crucial for civilians and the military.

More than 2,600 people have been killed so far in Iran’s crackdown, according to the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency. NPR has not independently confirmed this figure. There are some signs demonstrations are easing in Iran, with President Trump saying the killing appeared to be ending, as Iran calls off executions.

Activists say many of the images and videos of protests that have emerged since the blackout have come via Starlink.

Farzaneh Badiei, an internet policy researcher who follows Iran, said it plays an important role in keeping the outside world, and people inside Iran, informed.

“Every time the government has shut down the internet they have killed many more people than when people had access to internet and could report it and could livestream it,” she said. “That’s why having access to internet that cannot be shut down is an enabler of human rights.”

With some 9,500 low-earth orbit satellites, Starlink’s constellation comprises about two-thirds of all active satellites around Earth. The satellites relay the internet from base stations on Earth to users with a Starlink receiver, or “dish,” that’s about the size of a computer monitor.

“The great thing about it is there’s no wire for the government to cut,” said Jonathan McDowell, a satellite expert with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. “It’s very hard to censor because the signal is coming from the sky, and so if you have one of these dishes, you don’t have to go through a local telecom provider.”

While Starlink’s satellite network forms a grid that blankets most of the Earth, it is not legal for use in every corner of the planet.

In 2022, SpaceX first made its satellite internet service available to people in Iran. The Iranian leadership, which tightly controls the internet, has pushed back. The authorities tried to quash Starlink’s use through regulation and legal protests against SpaceX. Last summer, the Iranian parliament criminalized the use of Starlink.

Regardless, the number of receivers in the country has grown, according to activists.

Ahmad Ahmadian, executive director of the non-profit Holistic Resilience, which helps Iranians circumvent internet censorship, estimated that there are some 50,000 units in the country. They are bought abroad, smuggled in and traded on the black market.

He and other activists say SpaceX appears to have made access free in the country, waiving its normal subscription fee. “We are glad that this has happened, and we confirmed it with the users inside Iran,” Ahmadian said.

Neither SpaceX nor the White House confirmed this with NPR. But the news comes after White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said President Trump and Elon Musk had spoken about the issue.

Ahmadian said about half of the receivers in Iran were in use, although he expected more to come online now that the service is free.

Critics, however, have long flagged what they see as risks in relying on internet infrastructure that is controlled by a private company.

“I’m always concerned that this technology depends on the whims of one individual,” Ahmadian said. He said he did not, however, think it was a major issue for Iranians at the moment, given U.S. political support for the protest movement.

In Iran, using Starlink devices carries substantial risk.

Rights groups have said the government has been hunting down people using these devices. Analysts and activists also say the authorities have been jamming Starlink’s signals, with mixed success.

“It looks like [the jamming is] neighborhood by neighborhood,” said Amir Rashidi, a cybersecurity and policy expert at Miaan Group, a human rights NGO. Rashidi said he has been in touch with people on the ground in Iran using Starlink, and believes its use cannot be suppressed.

“They don’t have — I think we should say, thanks to God — they don’t have the technology to be able to stop a Starlink,” he said.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

Authorities in Iran have implemented a near total shutdown of the internet in the country. It’s part of a crackdown on large-scale anti-government protests there. But some people on the ground are getting around this by using a satellite internet system called Starlink. NPR tech correspondent John Ruwitch is here to tell us about it. Hi, John.

JOHN RUWITCH, BYLINE: Hi, Ailsa.

CHANG: OK. So first, explain to people, what is Starlink?

RUWITCH: Yeah, Starlink is essentially high-speed internet that you can access from anywhere on Earth. It’s based on a constellation of some 9,500 space satellites in low Earth orbit. They’re about the size of a pickup truck, with big solar panels. And they’re arrayed in a grid kind of blanketing the Earth.

CHANG: OK, that sounds so high-tech. And how exactly do people on the ground get internet access from Starlink?

RUWITCH: Yeah, it’s pretty straightforward. You buy a receiver, which is a small satellite dish. You get a subscription. You know, Starlink is part of Elon Musk’s aerospace company, SpaceX. Then you plug it in, point it at the sky without obstructions and you’ve got internet, whether you’re in a remote, rural area with no broadband or on board a ship at sea, for instance. Wherever.

CHANG: Wherever, even in places like Iran where the government has shut off the internet.

RUWITCH: Yeah.

CHANG: And cut off cell service, right?

RUWITCH: Yeah, and also in conflict zones. You might remember when Russia invaded Ukraine a few years ago, Starlink became an essential communication tool for people there, as well as the military. But it can be particularly useful in situations like what’s happening in Iran. Here’s Jonathan McDowell. He’s a satellite expert with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

JONATHAN MCDOWELL: The great thing about it is there’s no wire for the government to cut. It’s very hard to censor because the signal is coming from the sky. And so if you have one of these dishes, you don’t have to go through a local telecom provider.

RUWITCH: So governments that want to control the internet or censor it, like Iran’s, don’t like this. In fact, Starlink is illegal to use in Iran.

CHANG: OK, but how widely used is Starlink in Iran?

RUWITCH: Yeah, I asked Ahmad Ahmadian about this. He runs a U.S. nonprofit called Holistic Resilience that helps Iranians get around internet censorship, including through Starlink. He estimates there are more than 50,000 Starlink devices in the country right now. They’re all bought in other countries, smuggled in, then traded on a black market. He says they go for about $700. He’s actually pretty hopeful about the power of this device in a place where the internet is, in normal circumstances, heavily censored.

AHMAD AHMADIAN: Once people get a glimpse of free internet, an uncensored internet, suddenly they realize what is the prison that they are living in.

RUWITCH: He says people on the ground are telling him that as of Tuesday, Starlink is actually free in Iran. There’s no subscription needed. I reached out to SpaceX and the White House, but neither has confirmed that.

CHANG: You said 50,000 Starlink devices in the country. But Iran has, like, 90 million people, right?

RUWITCH: Yeah.

CHANG: So can such a small number of Starlink terminals make a difference, ultimately?

RUWITCH: Yeah, well, look, this isn’t the first time that the government has curtailed internet access there. Farzaneh Badiei is an internet policy analyst who grew up in Iran, who now lives in New York. She says even a small window to the outside world is crucial.

FARZANEH BADIEI: Every time the government has shut down the internet, they have killed many more people than when people had access to internet and could report it and could livestream it.

RUWITCH: Activists say a lot of the images that we’ve seen from Iran since the internet blackout started last week have come via Starlink, including images that show violence and death. You know, more than 2,500 people have been killed so far in the crackdown, according to the U.S.-based human rights activist news agency. NPR has not independently confirmed that figure.

CHANG: But it just seems in this current climate in Iran, it could be very risky to use Starlink there, right?

RUWITCH: Yeah. I mean, as I mentioned, it’s illegal. You know, rights groups tell us that the government has been hunting down people using these devices. And they’re hearing from sources on the ground that the authorities have been jamming Starlink signals in parts of the country.

CHANG: That is NPR’s John Ruwitch. Thank you, John.

RUWITCH: You’re welcome.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.

Columbia student detained by ICE is abruptly released after Mamdani meets with Trump

Hours after the student was taken into custody in her campus apartment, she was released, after New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani expressed concerns about the arrest to President Trump.

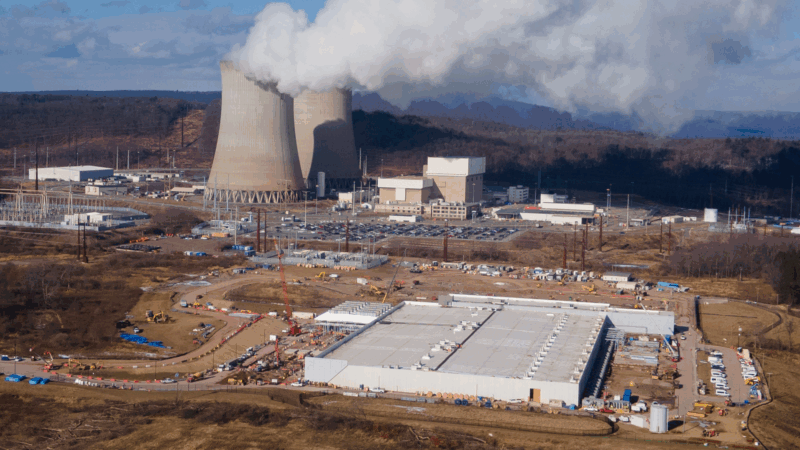

These major issues have brought together Democrats and Republicans in states

Across the country, Republicans and Democrats have found bipartisan agreement on regulating artificial intelligence and data centers. But it's not just big tech aligning the two parties.

Feds announce $4.1 billion loan for electric power expansion in Alabama

Federal energy officials said the loan will save customers money as the companies undertake a huge expansion driven by demand from computer data centers.

Mortgage rates fall below 6% for the first time in years

The average home loan rate has dropped below 6% for the first time since 2022. Will that help thaw the frozen housing market?