Their son was shot by police in Bangladesh’s 2024 protests. They still want justice

BABANPUR, Bangladesh — The monsoon rains lash down on this remote village in northern Bangladesh. Outside a modest mud house, several cows chew lazily on cud inside their pens, while a hen struts across the sodden courtyard, her five chicks in tow.

Abu Sayed’s elderly parents sit quietly on the veranda, staring at the deluge, their minds seemingly elsewhere.

To an unsuspecting passerby, it looks like a peaceful scene — albeit an impoverished one.

But after a closer look at the home, a stark image comes into focus: Dozens of posters and photos of Sayed line the path to the house, and surround his grave nearby.

Some show him with his arms outstretched, bearing his chest as he confronts police on July 16 last year outside his university in the northern district of Rangpur, just moments before officers shot him four times at close range.

His death, and the events surrounding it, were part of one of the most significant political upheavals in Bangladesh in decades.

Thirty-six days of nationwide unrest left as many as 1,400 people dead and thousands more injured, mostly at the hands of the security forces, according to the United Nations.

Other posters bear the words shahid — the Arabic word for “martyr” — across them.

They are a constant reminder to his family of his role in the student-led protests that started earlier that month — and the price he paid.

His father, Mokbul Hussein, tells NPR the 24-year-old was a quiet, polite young man who excelled in his studies.

“My son graduated with honors,” he says, his voice trembling with emotion. “He really struggled. I couldn’t afford his education, so he worked and paid for it himself. He was about to get a job when the protests began. Now he’s a martyr. When I think of it, my eyes fill with tears and my heart aches.”

Sayed’s mother, Monowara Khatun, sighs deeply. “I look at my son’s photo every day,” she says. “But it brings no peace. My days are filled with pain. He loved me so much.”

Sayed’s shooting was captured live on television. The footage showed him unarmed and posing no threat. It quickly went viral and marked a turning point in the protests, which had begun as demands to reform civil service job quotas, 30% of which were reserved for descendants of freedom fighters from the 1971 War of Independence.

Sayed died within 20 minutes of being shot.

Immediately afterward, the protests shifted. The demand was simple: Sheikh Hasina, who had ruled as prime minister for 15 years, had to go.

They ended with Hasina fleeing to India by helicopter. She now faces charges of crimes against humanity in Bangladesh.

Meanwhile, a tribunal has been set up to bring to justice those responsible for the deaths during the protests — but the process is taking time.

The interim government, formed shortly afterward under the leadership of Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, was widely hailed as a new chapter for Bangladesh: a chance to repair years of authoritarian rule, enforced disappearances, corruption and human rights abuses.

A growing sense of disillusionment

But 12 months on, a growing sense of disillusionment is sweeping across the country.

Critics accuse the new government of failing to tackle mob violence, and attacks on women and minority groups.

At the same time unemployment remains high.

Anu Muhammad, an economist based in the town of Savar, just north of Dhaka, says internal divisions within the coalition are partly to blame.

“Some groups were very much intolerant, some groups were secular,” he says, “so these were the differences. People are getting more and more frustrated because of the inaction, because of the lack of coordination among themselves, lack of coordination with the government and bureaucracy, government and police, government and judiciary.”

The protection of Bangladesh’s minority communities, especially Hindus, was one issue about which hopes were highest.

At Dhaka’s Dhakeshwara Temple, the largest Hindu temple in the country, police stand guard at the gates. Inside, however, the mood is jovial: worshippers take selfies and chat among themselves.

A wedding is underway. The bride is resplendent in red and gold. The groom is adorned with a garland of fresh flowers.

Adrita Roy, a drama student, who took part in last year’s protests, says it’s a misconception that Hasina’s Awami League political party protected her community.

“My grandfather was a Hindu freedom fighter,” she says. “All of his properties were confiscated by Awami League leaders, and they literally made a party office out of his ancestral home. These were the things that were going on.”

But she adds that despite promises made by Yunus to protect minorities, little has changed.

“Before the Yunus government came to power, he promised he would take care of the minorities,” she says, “which was very reassuring. But then the Awami League propaganda started flooding in. That’s when the government should have played a stronger role and prevented the very big incidents that have happened over the last couple of months.”

The Awami League declined NPR’s request for comment.

“We are simply not a mature democracy”

Yunus’ press secretary, Shafiqul Alam, defends the administration’s record on tackling crime.

He points to reforms in law and order, human rights, and transparency as evidence of progress.

“The most difficult task for this government was to manage expectations,” he told NPR.

“Some of these guys who criticize us, they wanted us to behave like a very mature democracy, which Bangladesh is not. It’s not like the United Kingdom or Scandinavian countries. We’re simply not a mature democracy.”

Back in Babanpur, as the rain continues to fall, Sayed’s father says he has one final request:

“Abu Sayed gave his life for his country. Now I ask the government for justice.”

Only then, he says, will he and his wife find peace.

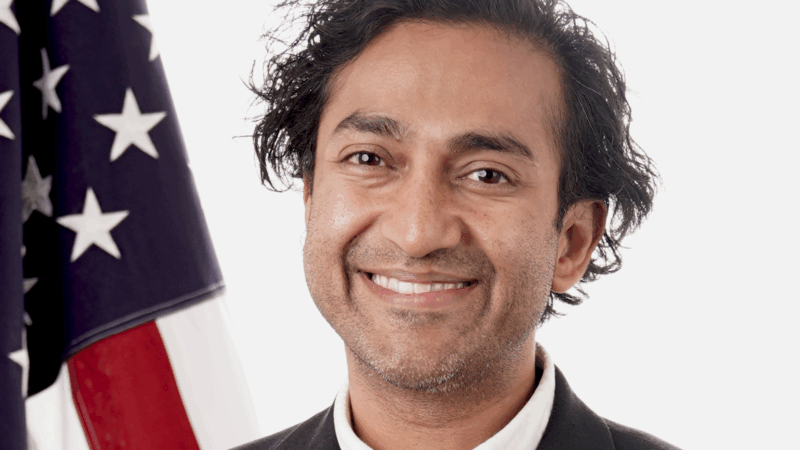

Trump administration’s embattled FDA vaccine chief is leaving for the second time

The FDA's controversial vaccine chief, Dr. Vinay Prasad, is leaving the agency. It's the second time he has abruptly departed following decisions involving the review of vaccinations and specialty drugs.

Family, former presidents and a Hall of Famer give Rev. Jesse Jackson a final sendoff

Several speakers at Jackson's funeral invoked his hallmark catchphrases: "Keep hope alive" and "I am somebody."

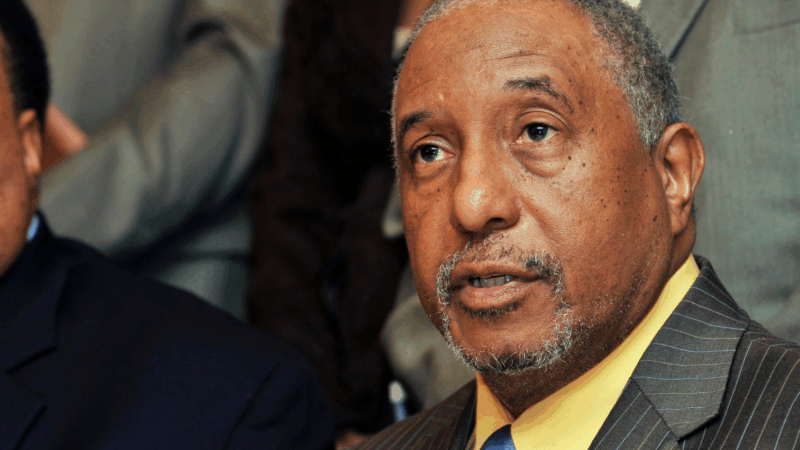

Bernard LaFayette, Selma voting rights organizer, dies at 85

Bernard LaFayette, who died Thursday, laid the foundations of the Selma, Alabama, campaign that culminated in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. He was a Freedom Rider and helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Oil surges to its highest price since 2023, and stocks drop after U.S. jobs report

Stocks fell Friday on worries that the economy could become stuck in a worst-case scenario of stagnating growth and high inflation. Oil prices touched their highest levels since 2023 after surging again because of the Iran war.

No lawsuits required: U.S. Customs is working on a system to refund tariffs

U.S. Customs told the trade court it aims for a streamlined process in 45 days to return importers' money without requiring individual lawsuits.

Poll: A majority of Americans opposes U.S. military action in Iran

Most Americans disapprove of President Trump's handling of Iran, and a majority sees Iran as either only a minor threat or no threat at all, an NPR/PBS News/Marist poll finds.