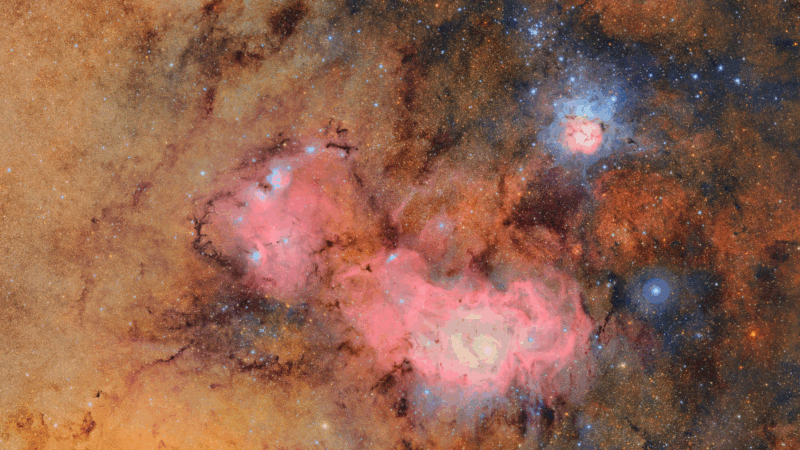

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s first images are stunning — and just the start

A powerful new observatory has unveiled its first images to the public, showing off what it can do as it gets ready to start its main mission: making a vivid time-lapse video of the night sky that will let astronomers study all the cosmic events that occur over ten years.

“As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. But a snapshot doesn’t tell the whole story. And what astronomy has given us mostly so far are just snapshots,” says Yusra AlSayyad, a Princeton University researcher who oversees image processing for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

“The sky and the world aren’t static,” she points out. “There’s asteroids zipping by, supernovae exploding.”

And the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, conceived nearly 30 years ago, is designed to capture all of it.

“These images are fantastic. They’re incredibly high resolution. But they’re just a tiny, tiny fraction of what’s been captured,” says Kevin Reil, a staff scientist with SLAC National Accelerator Lab who is working at the observatory in Chile. He notes that the newly released image that shows many galaxies is small section of the observatory’s total view of the Virgo cluster. “We just happened to zoom in on this little piece.”

Built with funding from the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, the facility will collect a mind-boggling amount of data on the entire southern night sky during a decade-long survey slated to start later this year.

This survey will compile observations on about 40 billion stars, galaxies and other celestial objects. Each one will be checked out hundreds of times, giving astronomers access to about 60 petabytes of raw data, which the Rubin Observatory says is “more data than everything that’s ever been written in any language in human history.”

“Since we take images of the night sky so quickly and so often, we’ll detect millions of changing objects literally every night,” says Aaron Roodman of Stanford’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, who is part of the observatory’s leadership team.

He calls the Rubin Observatory a “discovery machine” that will enable astronomers to “explore galaxies, stars in the Milky Way, objects in the solar system, and all in a truly new way.”

Already, in just over 10 hours of test observations, the observatory has discovered 2,104 never-before-seen-asteroids, including seven near-Earth asteroids, none of which pose any danger.

Mining the data

Named after an astronomer famous for her research related to dark matter, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is perched on a mountaintop in Chile. It’s equipped with a specially-designed large telescope, as well as a car-sized digital camera that’s the biggest such camera in the world.

The camera is controlled by an automated system that moves and points the telescope, snapping pictures again and again, to cover the entire sky every few days. Each image is so detailed, displaying it would take 400 ultra high-definition television screens.

By constantly comparing new images to ones taken before, the facility’s computer systems will be able to spot anything in the sky that changes or moves or goes boom.

“It will be capable of really detecting things that actually change very rapidly,” says Sandrine Thomas, deputy director of Rubin Observatory and the observatory’s telescope and site project scientist. “That, in itself, will be unique to the world. No other telescope would be able to do that.”

“It has such a wide field of view and such a rapid cadence that we do have that movie-like aspect to the night sky,” she says.

The observatory is expected to detect about 10 million changes every night, and will send out alerts to consortiums of researchers. They’ll analyze all that data and zero in on the most interesting changes to target for follow-up observations.

This should let astronomers catch transient phenomena that they otherwise wouldn’t know to look for, such as exploding stars, asteroids, interstellar objects whizzing in from other solar systems, and maybe even the movement of a giant planet that some believe is lurking out in our own solar system, beyond Pluto.

“It’s a very special telescope,” says Scott Sheppard, an astronomer with Carnegie Science. “It’s going to find everything that goes bump in the night, to some degree.”

“It’s going to be revolutionary,” he says. “Astronomers are going to change from observing little areas of the sky to basically data mining. It’s going to be like a firehose of data coming in. There’s going to be all kinds of stuff in there and we’re going to have to sift through it to find everything.”

U.S. House rejects aviation safety bill after Pentagon abruptly withdraws support

The House of Representatives narrowly rejected a bipartisan aviation safety bill that was spurred by the deadly midair collision near Washington, D.C. after the Pentagon abruptly withdrew its support.

China and the US alter foreign aid strategies

China's foreign aid strategy has shifted in the last few decades and now its model may be the one the US is adopting as China moves away from it.

Flavor Flav is among women’s hockey team fans outraged by presidential snub

The rapper, who also serves as the official "hype man" for multiple U.S. Olympic teams, invited the female hockey players to Las Vegas for a "real celebration."

Flavor Flav is among women’s hockey team fans outraged by presidential snub

The rapper, who also serves as the official "hype man" for multiple U.S. Olympic teams, invited the female hockey players to Las Vegas for a "real celebration."

Flavor Flav is among women’s hockey team fans outraged by presidential snub

The rapper, who also serves as the official "hype man" for multiple U.S. Olympic teams, invited the female hockey players to Las Vegas for a "real celebration."

Flavor Flav is among women’s hockey team fans outraged by presidential snub

The rapper, who also serves as the official "hype man" for multiple U.S. Olympic teams, invited the female hockey players to Las Vegas for a "real celebration."