The legacy of Hulk Hogan’s sex tape scandal

For decades Hulk Hogan, the larger than life wrestling character whose given name is Terry Bollea, dominated American popular culture. He helped thrust pro-wrestling onto the world stage, starred in television shows, movies and cartoons. But it was much later in his life that he also dominated legal discussions about the First Amendment and celebrities’ right to privacy.

His body slam of a victory over Gawker Media in 2016 will be remembered as part of the wrestler’s legacy, following his death at the age of 71 on Thursday. Although the case didn’t set new legal precedent it was a jolt to the system for the media. It showed the limits of First Amendment protections when it came to explicit video and demonstrated to regular people that they had the right to privacy in the digital age. It also made clear the idea that even if something is newsworthy, showing graphic depictions of it constitutes an invasion of privacy.

Backed by billionaire Peter Thiel, who had been outed as gay by the outlet, Hogan sued Gawker, a news and gossip site, after it published a surreptitiously videotaped sexual encounter between Hogan and the wife of a former friend. The black and white video was published under the headline, “Even for a Minute, Watching Hulk Hogan Have Sex in a Canopy Bed is Not Safe For Work But Watch It Anyway” and was accompanied by a lengthy article describing the tryst.

Throughout the civil suit, Hogan maintained he was unaware that he was being taped and that publication of the sexual encounter was an invasion of privacy. Meanwhile, Gawker attorneys said it got the tape through an anonymous source and argued it had the right to publish news that is true. In the end a Florida jury awarded Hogan $140 million in the civil suit, ultimately leading to the demise of Gawker Media.

The case raised major questions about the line between freedom of expression and privacy, and what is actually newsworthy. Questions that needed to be reexamined in light of the invention of the internet, Amy Gajda, a Brooklyn Law School professor told NPR.

“Some of my research has shown that previously, privacy really wasn’t much of an issue, because before the internet the only publishers mainly were mainstream news, media outlets and ethics restrictions kept those people from publishing deeply personal information,” Gajda, a First Amendment law expert, said.

Those outlets did a lot of self-censoring when it came to deeply personal information, including nudity or graphic sexual information, and medical records, which are protected under existing privacy laws, she said. But in the age of the internet, it was unclear if those same guardrails were expected to stay in place.

Rodney Smolla, president of the Vermont Law and Graduate School said Hogan v. Gawker proved “to be a turning point case in the culture or media law,” even though it did not set any new legal precedents.

“If they’d published still photos or even pixelated the most graphic parts of the video, Gawker could have gotten away with it. They would have won their case under the existing freedom of the press laws,” Smolla, a First Amendment scholar, told NPR.

“Normally, usually, Freedom of the Press trumps privacy laws but by showing actual sexual intercourse, in the eyes of a lot of people, [Gawker] just went too far.”

“In the past, things were left to our imagination,” Gajda said. Media outlets seeking to push the envelope might choose to run racy photographs using black bars over nude body parts when they wanted to publish titillating information. But, Gajda stressed, they knew if they took it too far, there would be a lawsuit or backlash from readers.

While Hogan’s verdict was a coup for celebrities, Gajda said his legacy is one that is more relevant for regular people because it taught them about their own rights when it comes to a breach of privacy, even when something is true. That is especially relevant for people caught in cases of revenge porn, Gajda explained. Many people wrongly believed, she said, that if they shared nude images of themselves to someone else, the other person had the power to publish such images.

Smolla said the repercussions of the lawsuit have been primarily felt by “responsible media, who now feel even more pressure to abide by journalistic standards and not expose themselves to bankruptcy.”

“It was a shot against the bow,” the First Amendment scholar noted, adding that the case also “established the notion that it’s just not true that anything goes, and it’s just not true that you can show anything about anybody that’s a celebrity, and feel that you have no liability for invading their privacy.”

In this Icelandic drama, a couple quietly drifts apart

Icelandic director Hlynur Pálmason weaves scenes of quiet domestic life against the backdrop of an arresting landscape in his newest film.

After the Fall: How Olympic figure skaters soar after stumbling on the ice

Olympic figure skating is often seems to take athletes to the very edge of perfection, but even the greatest stumble and fall. How do they pull themselves together again on the biggest world stage? Toughness, poise and practice.

They’re cured of leprosy. Why do they still live in leprosy colonies?

Leprosy is one of the least contagious diseases around — and perhaps one of the most misunderstood. The colonies are relics of a not-too-distant past when those diagnosed with leprosy were exiled.

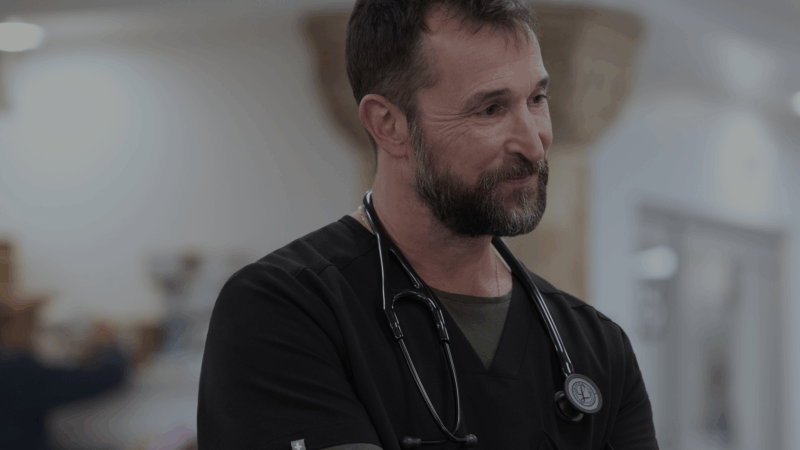

This season, ‘The Pitt’ is about what doesn’t happen in one day

The first season of The Pitt was about acute problems. The second is about chronic ones.

Lindsey Vonn is set to ski the Olympic downhill race with a torn ACL. How?

An ACL tear would keep almost any other athlete from competing -- but not Lindsey Vonn, the 41-year-old superstar skier who is determined to cap off an incredible comeback from retirement with one last shot at an Olympic medal.

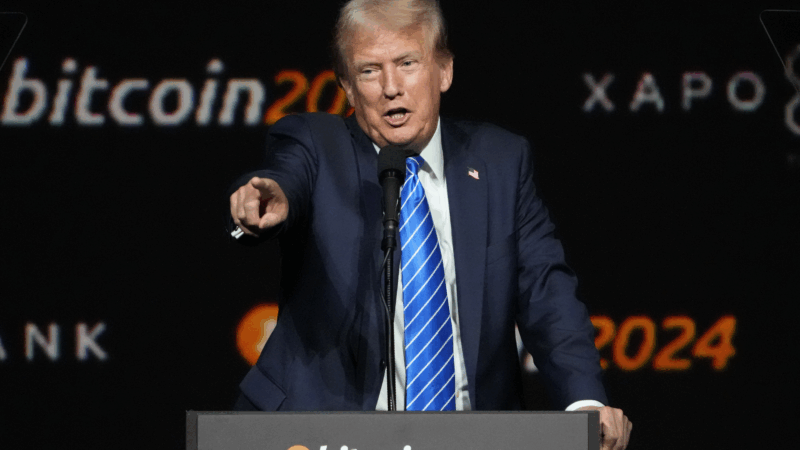

Trump promised a crypto revolution. So why is bitcoin crashing?

Trump got elected promising to usher in a crypto revolution. More than a year later, bitcoin's price has come tumbling down. What happened?