Syria, once home to a large Jewish community, takes steps to return property to Jews

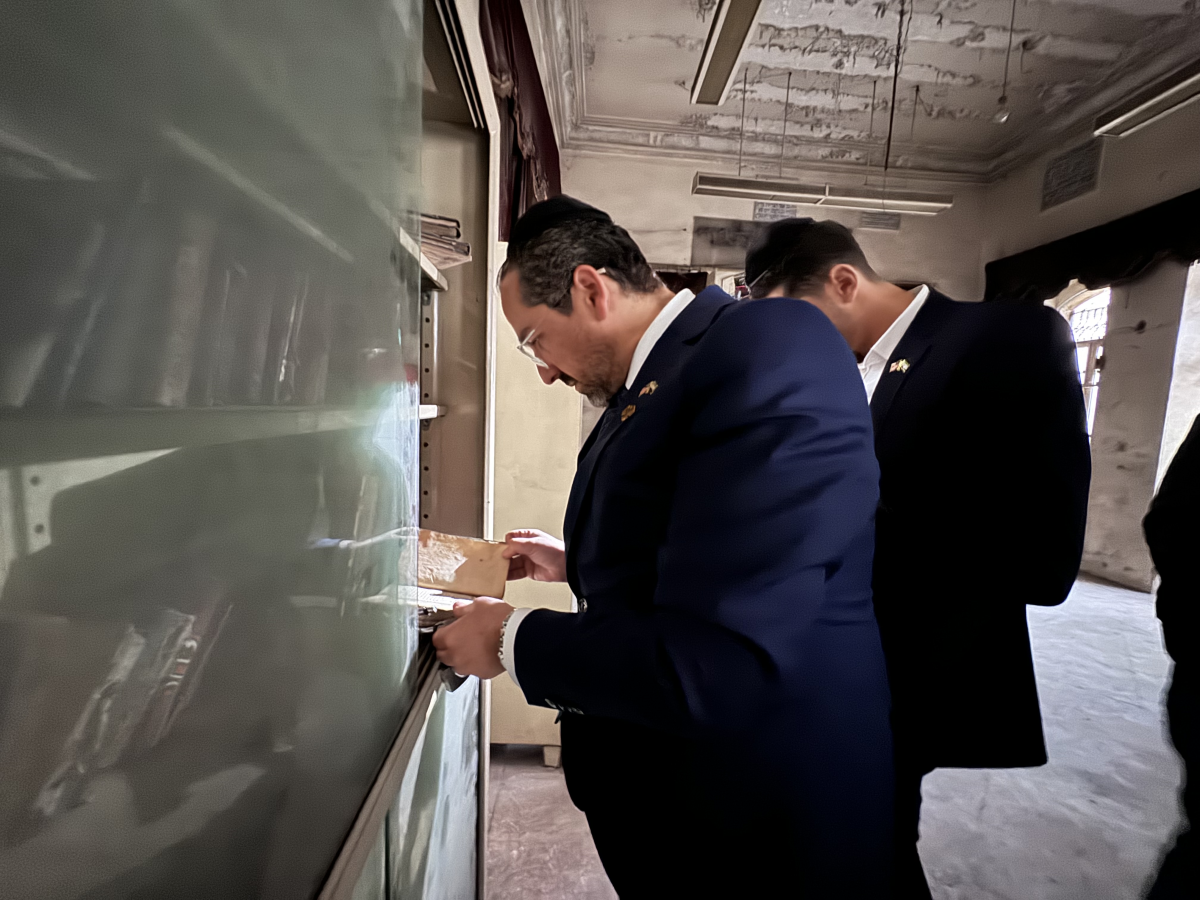

ALEPPO, Syria — Decades after almost the entire Syrian Jewish community left the country, Henry Hamra of Brooklyn, N.Y., stands at the metal door of a small synagogue in this ancient Syrian city, literally holding the keys to a possible return of Jewish citizens.

Hamra was 15 years old when his family left Damascus in the early 1990s after the Assad regime lifted a ban on travel. Many of the Syrian Jews were unable to sell their homes before they left. Some of the homes ended up occupied by other Syrians while the government took charge of the synagogues and schools.

In December, just days before Hamra’s visit to Aleppo, the Syrian government licensed a Jewish heritage foundation he leads, transferring control of Jewish religious properties from the government to the organization.

The organization will also help restore private property appropriated when the Jewish community left to its Jewish owners.

“What we’re trying to do is come see the properties, come see the synagogues and see what’s the condition,” says Hamra, now 48. “I’m calling on all the people who have properties to come and we’ll help them find them and give them back to them.”

A remarkable journey over the past year largely engineered by Syrian-American activist Mouaz Moustafa has led Hamra to this day, taking custody of the keys to Jewish properties by the latest in a series of caretakers over decades and envisioning a time when Syrian Jews might return.

On Hamra’s first visit to Syria with his father last year, Syrian government officials pledged help in restoring properties back to their Jewish owners.

In a wrinkle of history, the new Syrian president restoring Jewish rights, Ahmed al-Sharaa, is a onetime al-Qaida commander who renounced the militant Islamist group’s ideology.

Aleppo, in northern Syria, had one of the biggest Jewish communities in this diverse but mostly Arab country — dating back at least 2,000 years.

Before the creation of Israel in 1948, there were an estimated 30,000 Jews in Syria. Syrian Jews in modern history were able to practice their faith but faced the same repressive policies under the closed regime as other citizens. When President Hafez al-Assad, under U.S. pressure, lifted travel restrictions specifically for Jewish citizens beginning in 1992, most of them left permanently.

Hamra’s father, Yusuf Hamra, was the last rabbi to leave Syria. Without someone to perform ceremonies, Jewish religious life here died.

Now, only six Syrian Jews — all elderly — are known to still live in the country, says Hamra. When Rabbi Hamra made his first trip to Damascus last year since leaving three decades ago, there were not enough Jews even with his visiting delegation to be able to hold prayers.

On this trip, Henry Hamra has brought his 21-year-old son, Joseph, with him.

Hamra opens the door to a small synagogue with layers of dust coating the heavy burgundy velvet curtains. Next to it is a small school. Dim light filtering through grime-coated windows reveals stacks of desks piled up on scuffed wooden tables.

The synagogue is in an Aleppo neighborhood heavily damaged in Syria’s 14-year-long civil war. That conflict ended when opposition fighters toppled authoritarian President Bashar al-Assad in December 2024.

Next door, the owner of a tiny neighboring plumbing supply shop says he is happy that Syria is helping Jewish citizens return.

“They were our friends,” says Abu Alaa al-Muhandis, 75. “We hope they will come back, they will bring life back to the city.”

While Israel, which has seized more Syrian territory and launched regular airstrikes, is controversial in Syria, Syrian American Jews are viewed for the most part simply as Syrian.

“Always in Syria you know we had churches, synagogues and mosques together in the same area because people used to live together, as neighbors,” says Maissa Kabbani, the founder of a Syrian justice organization. She points out a damaged mosque close to the synagogue.

Across town, Hamra is shown for the first time the jewel of Aleppo’s once-thriving Jewish community — the Central Synagogue, also known as the al-Bandara Synagogue, named after the neighborhood it’s located in.

The scale of the 1,500-year-old synagogue speaks to a once large and vibrant Jewish community in a city that for many centuries was a thriving trade center.

Inside, stone arches top Roman columns overlooking courtyard after courtyard. There are marble-tile floors and an ornate women’s section on the second floor, where women and girls could participate in prayers behind decorative iron screens without being seen.

In New York, Hamra’s family is in the menswear business. In religious life he is a cantor — a clergy member who leads the congregation in prayers and song.

Hamra wanders through the open spaces of the synagogue, stepping up onto an elevated marble platform where cantors have stood over the centuries.

“Wow,” he says repeatedly, seemingly at a loss of words over his surroundings.

The central synagogue was also for hundreds of years the home to a Hebrew manuscript known as the Aleppo Codex. The 1,000-year-old manuscript is the oldest known surviving copy of the Hebrew Bible. The codex was smuggled to Israel in the 1950s although only partially intact.

Syrian President Sharaa has been keen to reassure the West that minorities will be protected in the new Syria. The Syrian government, in announcing that it was handing over Jewish religious properties, said it was a sign that all minorities were welcome.

In Washington, D.C., the Syrian Jewish community represented by the Hamras, working with Mouaz Moustafa’s Syrian Emergency Task Force, have proved effective advocates for lifting U.S. sanctions against Syria. The U.S. removed the last of the devastating trade sanctions in December.

That advocacy has generated controversy among some Syrian-American Jews who believe that Sharaa and his government cannot be trusted to protect Jews or other Syrian minorities.

“It’s going to take a lot of time for Syria to come back,” says Hamra, citing a lack of electricity, running water and in places like Aleppo, security.

In Damascus and Aleppo, the small delegation is accompanied by young Syrian government fighters with rifles. Some ask to pose for selfies with Hamra.

Hamra grew up speaking Arabic at home. He refers to Syria as “the old country.”

He says while it is a stretch now to envision Syrian Jews moving here, he says many would cherish the opportunity to visit.

“There’s a lot of things we used to do over here we don’t do in the U.S. — like the interaction with people,” he says. “Syrian people are very loving people and they’re very welcoming.”

His son Joseph says he can’t stop smiling.

“You see my face?” he asks. “I’ve never had this face in my life. It’s crazy.”

Joseph Hamra says, for his part, he can envision younger Syrian Jews coming to live.

“I’m planning on making a trip with all my friends soon to see all their roots, like where their parents and grandparents grew up, where some of their grandparents are buried,” he says. “They would 100% think in the back of their heads, ‘Wow imagine building something here.'”

Feds announce $4.1 billion loan for electric power expansion in Alabama

Federal energy officials said the loan will save customers money as the companies undertake a huge expansion driven by demand from computer data centers.

Mortgage rates fall below 6% for the first time in years

The average home loan rate has dropped below 6% for the first time since 2022. Will that help thaw the frozen housing market?

Baby Keem’s boulevard of broken dreams

Ca$ino, the rapper's second album for his cousin Kendrick Lamar's label, is whiplash embodied, a mirror for the extreme highs and lows of his Sin City hometown.

Pentagon shifts toward maintaining ties to Scouting

Months after NPR reported on the Pentagon's efforts to sever ties with Scouting America, efforts to maintain the partnership have new momentum

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Tariffs cost American shoppers. They’re unlikely to get that money back

After the Supreme Court declared the emergency tariffs illegal, the refund process will be messy and will go to businesses first.