Sick young ants send out a ‘kill me’ scent to prevent deadly epidemics

Scientists studying the way ant colonies defend against disease have discovered a surprising strategy: Young ants who become terminally ill will send out an altruistic “kill me” signal for the worker ants who tend to them.

The findings, described in the journal Nature Communications, add to a growing understanding of the complex ways these highly social animals try to keep deadly epidemics in check.

Social insect colonies are a great place for an epidemic to spread, according to Neil Tsutsui, a behavioral ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the research.

With so many insects packed together in moist and dark places — and all closely related, sharing the same genetic vulnerabilities — infections and diseases can quickly pose an enormous threat to the well-being of an ant colony. “If one individual is susceptible,” Tsutsui explains, “lots of other individuals in society will be susceptible.”

To manage these risks, ants have evolved with multiple disease defense strategies that depend on individuals collaborating to function as a whole — similar to how the human body’s immune system works.

In some species, ants restructure their nests to slow the transmission of a lethal fungus and in others, ant queens eat infected brood to prevent the spread of disease and recover nutrients. Some of these strategies are even described by scientists as “altruistic” — take the way that sick adult ants will “socially distance,” wandering away from the colony to avoid infecting their nestmates.

But pupae — which are the young ants still growing, often in a silk cocoon, being tended to by adult worker ants — can’t yet move. That means that if they get sick and become infectious, they pose a serious risk to the entire colony.

Sylvia Cremer, the report’s senior author, is a professor at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria. A few years ago, the social immunity research group she leads discovered a phenomenon called “destructive disinfection.”

When a young ant is terminally ill, an adult worker ant will unpack the sick pupa’s cocoon and apply a self-produced disinfectant, which eventually kills the young ant. “Interestingly, this also occurs at the time where the pupa is not infectious, but it will become [so] if it is not treated,” Cremer says.

But they still didn’t know if the destructive disinfection was a passive behavior as part of the colony’s immune response or if the young ants were actively putting out an altruistic signal to sacrifice themselves for the good of their colony.

To find out, they teamed up with Thomas Schmitt, a chemical ecologist from the University of Würzburg, and studied the invasive garden ant species Lasius neglectus.

They started by testing which situations led the sick young ants to emit the signal. When they left the infected pupa by itself, there was no signal. It was only when they put in adult worker ants that could disinfect and kill them that the sick pupa put out the signal, which comes in the form of a smell.

Producing the smell takes up a lot of the pupa’s limited resources, so it made sense to the researchers that it would only send out the signal if there were worker ants around to pick it up. They also found that only young worker ants and not queen pupae send out the “kill me” signal because the young queens have the ability to fight off infection, while worker ants could easily spread the infection because of their weaker immune systems.

But to prove this was a causal relationship and not just a correlation, Cremer and her team took it a step further by designing an experiment. They transferred the smell the sick young ants produced to a healthy pupa, which they then put with an adult worker ant to see what would happen.

The scientists found that even though the young ant was perfectly healthy, the worker ant started unpacking the pupa’s cocoon, proving the smell was the active call to action.

However, Cremer and Tsutsui say that calling the behavior in ants “altruistic” might be a bit of a misnomer because the ants making the sacrifice still stand to benefit, although indirectly.

That’s because, since most ants are sterile, they rely on the colony as a whole to continue passing on their genes.

“From that perspective, it’s kind of a selfish behavior, right?” Tsutsui says. “It’s doing the thing that is best for them to pass on their genes. And it just so happens that in this circumstance, the best thing is to sacrifice yourself — and let others carry your genes into the future.”

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

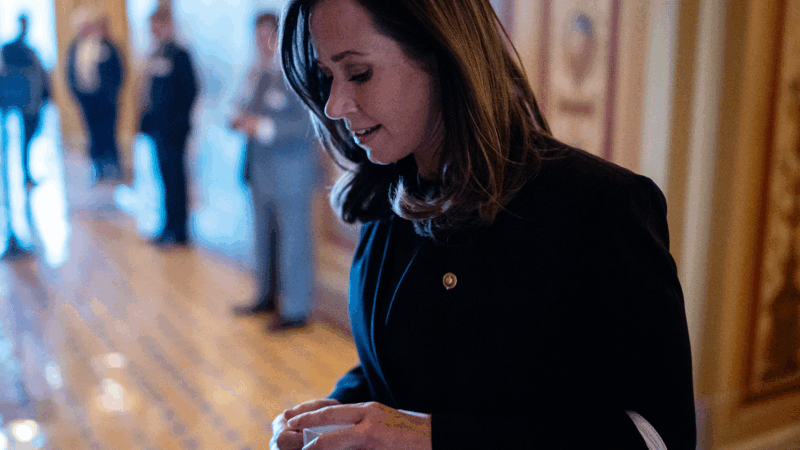

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country