Searching for dinosaur secrets in crocodile bones

Until now, estimating how old a dinosaur was when it died has been a fairly simple process — just count up the growth rings in its fossilized bones.

“We always thought that those rings were formed annually,” says Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, a paleobiologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. In other words, much like tree rings, the idea was that roughly one ring was laid down each year.

“And then you can plot that and you can work out the growth rate of the dinosaur,” explains Chinsamy-Turan. “And that’s what all of us were doing — me included.” For example, this technique suggested that it took 20-some years for a T. rex hatchling to grow into a fully grown adult, she says.

But this approach may overestimate dinosaur ages. In a study published in the journal Scientific Reports, Chinsamy-Turan and her colleague, biologist Maria Eugenia Pereyra, looked at the growth rings in several young Nile crocodiles — a modern relative of dinosaurs. In some of the bones, the two researchers found more growth rings than they were expecting.

If the same was true in dinosaurs, some of these specimens were likely younger than scientists once thought.

A modern-day animal to understand dinosaur growth

An ideal way to confirm the one-ring-per-year aging approach would be to study live dinosaurs. That’s an unlikely proposition, given that dinosaurs have been extinct for more than 65 million years. Instead, researchers often turn to their living relatives — like birds and crocodiles.

Just outside of Cape Town, a flotilla of Nile crocs lurks in the pools beneath a network of pedestrian bridges at Le Bonheur Reptiles & Adventures. “They’re basically the kings of the water bodies in Africa,” says Alzette Mocké, who manages the facility.

At last count, there were 177 of the animals at this outdoor recreation and education center. “We respect them,” says Mocké. “And we basically let them be. We give them what they need and we offer viewing opportunities.”

On a recent morning, Chinsamy-Turan snaps photos of the beasts below. “Really gorgeous,” she says. “Each of them, their skeletons tell a story about how they grew. So we can say so much about the biology of dinosaurs because we have them as a model to understand dinosaur growth.”

In short, Mocké says, “it’s like walking among dinosaurs every day. I’m quite tickled by it, I must say.”

Chinsamy-Turan initially set out to understand how a crocodile’s environment impacts its own skeletal growth. The dinosaur insights would come later.

In 2011, she and Le Bonheur teamed up to inject several year-old crocodiles with an antibiotic three times over multiple months. “The antibiotic actually gets taken up in the development of the bone,” says Chinsamy-Turan, leaving chemical time markers in the tissue as the animal grows.

Even before the analysis, it was clear that these four crocodiles had unique growth trajectories. “They hatch together, they grow together, but they have different sizes,” says Pereyra. “Individually, they have different stories.”

Andrea Plos, a technical officer at the University of Cape Town, came by regularly to measure, weigh and wrangle the animals. The largest individual grew to more than 80 pounds.

“It almost became too difficult to pick him up on my own,” she recalls. “He was definitely a bully — he tried to bully me and he won. So I had to bring in help!”

Back when all this was happening more than a decade ago, Le Bonheur used to farm and kill their crocodiles to sell the leather and meat. That’s no longer the case. The staff says the animals now live out their natural lifespans.

But in 2013, when those four crocs were two years old, Le Bonheur got their leather — and Chinsamy-Turan got their bones.

Croc around the clock

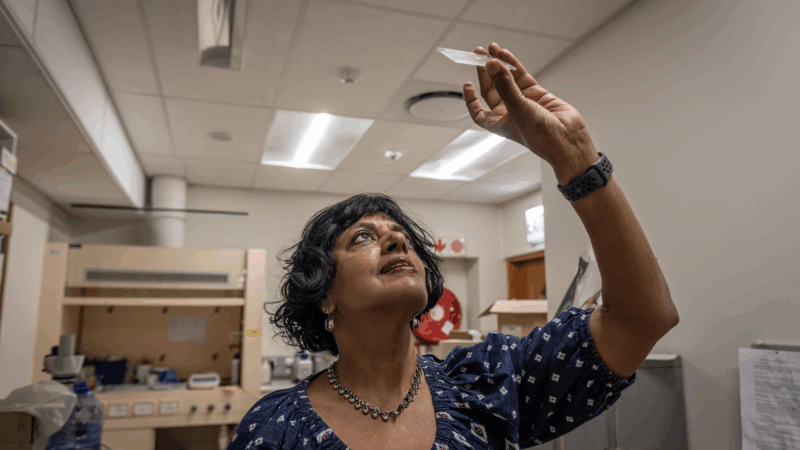

In her lab at the University of Cape Town, Chinsamy-Turan rifles through several slides, each one containing a super thin cross-section of a crocodile arm bone or leg bone.

Pereyra was the one who prepared the slides, polishing them until the growth rings were beautifully visible. “The time that the light goes through the section and you actually can see all the structures is the time that you know that the section is the good one,” she says.

Chinsamy-Turan holds one of the slices up to the light. “Look at that. You can see some lines,” she says, pointing to some faint banding. “Under the microscope, they’ll be more visible.”

Indeed, when the two researchers looked at these slices under the microscope, they saw something that caught their attention — more rings in some of the bones than they were expecting.

“This is a two-year-old crocodile,” says Chinsamy-Turan. “And in many cases, we found up to five growth marks in the bones.”

If they didn’t know how old the animals were, they might have thought they were five years old. However, “we know exactly how old the animal was when we gave the injections,” says Chinsamy-Turan. “So there were extra growth marks formed during their short life.”

It’s a result that may have implications for the rings in dinosaur bones. Specifically, the crocodile findings — alongside similar results from other reptiles as well as kiwi birds — suggest at least some dinos may have been younger when they perished than previously thought.

“It changes how we think about dinosaur growth and how we can use growth marks to determine dinosaur growth patterns,” says Chinsamy-Turan. She concludes that these marks may be better thought of as cycles of growth.

“A cautionary tale”

“Studies like this one are really important in adding to that body of knowledge of how often growth rings can be reliable,” says Holly Woodward, a paleohistologist at Oklahoma State University who wasn’t involved in the study. “We haven’t really done as much ground-truthing as we could with modern animals,” she says.

Woodward doesn’t believe the matter is settled since some animals show annual growth rings, while others don’t. “It’s very weird but we can’t say why or what causes it specifically,” she says. Perhaps, she suggests, it’s due to differences in hormones or day/night cycles. Until researchers know more, however, she argues that growth rings remain useful as a starting point for understanding dinosaur growth.

“It’s sort of a cautionary tale not to overinterpret what we can see and know based on bone tissue under the microscope,” says Kristi Curry Rogers, a dinosaur paleobiologist at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota who didn’t participate in the research.

“This confirmed a suspicion that I’ve often had in my own work,” she continues, “because we still don’t understand everything we need to about living vertebrates and how their bones respond to the environments around them.”

Andrew Lee, a paleontologist at Midwestern University who didn’t contribute to the study either, believes there were too many “different confounding variables” of raising the crocodiles in captivity to know what produced the extra growth rings in the bones. For instance, he says it could have been the added stress of living in close quarters or being fed on an artificial schedule. Either way, Lee feels the captive conditions didn’t adequately replicate what wild dinosaurs would have lived through millions of years ago.

As for Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, she argues that there’s more work to be done.

“We’ve always estimated the age of the dinosaur,” she says. “And what this means is that we can still get a rough estimate but people have to realize that it’s an estimation.”

Even though researchers may not understand the full picture yet, Chinsamy-Turan believes the answers are there, waiting for us.

“It’s all in the bones,” she says with a chuckle.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

This is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News. I’m Juana Summers.

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

And I’m Scott Detrow, and we are considering dinosaurs. What do you get when a team of researchers walks onto a crocodile farm? Answer – a different way of thinking about the age of a dinosaur. Here’s science reporter Ari Daniel.

ARI DANIEL, BYLINE: Until now, estimating how old a dinosaur was when it died has been a fairly simple process, says Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan. She’s a paleobiologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Just take those fossilized bones and count up the growth rings.

ANUSUYA CHINSAMY-TURAN: We always thought that these rings are formed annually.

DANIEL: Meaning, like a tree, you might imagine, one ring per year.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: Exactly. And then you can plot that and you can work out the growth rate of the dinosaur.

DANIEL: Such plots revealed how dinosaurs likely grew up.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: So, for example, how long did it take T. rex to grow from a hatchling to a fully grown adult?

DANIEL: Answer – 20-some years. But to really confirm this ring counting approach, you’d need to study live dinosaurs. The next best thing are their living relatives, like birds…

QUINTON CRONJE: So we’re going on our lovely crocodile tour now.

DANIEL: …And crocs.

CRONJE: We’ve got some big crocodiles in here. See the male’s head just moved a little bit to this side.

DANIEL: Quinton Cronje is the head animal handler here at Le Bonheur Reptiles and Adventures, an outdoor recreation and education center near Cape Town. A hundred seventy-some Nile crocodiles lurk in the pools beneath a network of pedestrian bridges.

(SOUNDBITE OF CAMERA SHUTTER CLICKING)

DANIEL: Chinsamy-Turan snaps photos of the beasts below.

(SOUNDBITE OF CAMERA SHUTTER CLICKING)

CHINSAMY-TURAN: Really gorgeous – each of them, their skeletons tell a story about how they grew.

DANIEL: Chinsamy-Turan initially set out to understand how a crocodile’s environment impacts its skeletal growth. So she and the team at Le Bonheur injected several year-old crocodiles with an antibiotic over multiple months.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: And the antibiotic actually gets taken up in the development of the bone that leaves a signal in the bone.

DANIEL: Serving as a time marker, essentially. Andrea Plos, a technical officer at the University of Cape Town, came by to measure and weigh the animals. The largest croc grew more than 80 pounds.

ANDREA PLOS: It almost became too difficult to pick him up on my own. He was definitely a bully, and he tried to bully me. And he won (laughter), so I had to bring in help.

DANIEL: All this happened more than a decade ago, back when this place used to raise and kill the crocodiles to sell their leather and meat. That’s no longer the case. But in 2013, when those four crocs were 2 years old, Le Bonheur got their leather and Chinsamy-Turan got their bones.

(SOUNDBITE OF INTERCOM RINGING)

DANIEL: Hey there.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: Hi. Hi, Ari. Welcome.

DANIEL: Thank you.

(SOUNDBITE OF DOOR CLOSING)

DANIEL: I paid Chinsamy-Turan a visit at her lab. She rifles through several slides, each one containing a super thin cross section of a crocodile bone. Biologist Maria Eugenia Pereyra prepared the slides, polishing them until the growth rings were beautifully visible.

MARIA EUGENIA PEREYRA: So the time that the light go through the section and you actually can see all the structures is the time that you know that the section is a good one.

DANIEL: When she and Chinsamy-Turan looked at the slices under the microscope, they found something unexpected.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: This is a 2-year-old crocodile, and in many cases, we found up to five growth marks in the bones. So there were extra growth marks formed during the short life.

DANIEL: Right. You might have thought they were 5 years old.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: Exactly.

DANIEL: It’s a result that may have implications for dinosaur bones. That is, the crocodile findings suggest at least some dinos may have been younger when they perished than previously thought. Similar results in other reptiles as well as kiwi birds back that up.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: It changes how we think about how we can use growth marks to determine dinosaur growth patterns.

DANIEL: Suggesting, she says, that these marks may be better thought of as cycles of growth. The results appear in the journal Scientific Reports. Holly Woodward is a paleohistologist at Oklahoma State University who wasn’t involved in the research.

HOLLY WOODWARD: Studies like this one are really important in adding to that body of knowledge of how often growth rings can be reliable.

DANIEL: But Woodward doesn’t believe the matter’s settled, since some animals show annual growth rings, while others don’t.

WOODWARD: It was very weird, but we can’t yet say why or what causes it specifically.

DANIEL: And until we do so, Woodward argues it’s premature to throw out using growth rings as annual age markers. For her, that’s at least a starting point for understanding dinosaur growth. As for Anusuya Chinsamy-Turan, she agrees there’s more work to be done, but she believes the answers may well be waiting for us.

CHINSAMY-TURAN: It’s all in the bones (laughter).

DANIEL: For NPR News, I’m Ari Daniel, Cape Town, South Africa.

DETROW: Ari’s reporting for the story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

Feds announce $4.1 billion loan for electric power expansion in Alabama

Federal energy officials said the loan will save customers money as the companies undertake a huge expansion driven by demand from computer data centers.

Mortgage rates fall below 6% for the first time in years

The average home loan rate has dropped below 6% for the first time since 2022. Will that help thaw the frozen housing market?

Baby Keem’s boulevard of broken dreams

Ca$ino, the rapper's second album for his cousin Kendrick Lamar's label, is whiplash embodied, a mirror for the extreme highs and lows of his Sin City hometown.

Pentagon shifts toward maintaining ties to Scouting

Months after NPR reported on the Pentagon's efforts to sever ties with Scouting America, efforts to maintain the partnership have new momentum

Why farmers in California are backing a giant solar farm

Many farmers have had to fallow land as a state law comes into effect limiting their access to water. There's now a push to develop some of that land… into solar farms.

Tariffs cost American shoppers. They’re unlikely to get that money back

After the Supreme Court declared the emergency tariffs illegal, the refund process will be messy and will go to businesses first.