Russia gives Ukrainian kids military training and reeducation, Yale researchers find

KYIV, Ukraine — A new report by Yale University researchers has uncovered evidence that Russia’s extensive network of sites where thousands of Ukrainian children are reeducated is larger than investigators had previously estimated, and appears to include military training at cadet academies and schools for children as young as 8.

The report by the Humanitarian Research Lab at the Yale School of Public Health, titled “Ukraine’s Stolen Children: Inside Russia’s Network of Re-Education and Militarization,” examines what’s happening to thousands of Ukrainian children taken from occupied areas, especially since Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Investigators say they have documented an extensive system where Russia routinely strips Ukrainian children of their cultural identity and teaches them Russian patriotic narratives and even combat skills.

“They’re giving them actual training in grenade throwing and, in one case we know they’re involved in the manufacture of drones,” Nathaniel Raymond, the lab’s director, said in an interview with NPR.

Russian authorities “are not taking them to paratrooper jump school to make them mall cops at the Cinnabon at Rostov-on-Don,” Raymond said, referring to a major regional city in Russia’s south.

“They are in a training pipeline that has tactical scenarios and curricula that lead only to one conclusion.”

The report documents 210 locations — 156 of them newly identified — across Russia and occupied Ukraine where Ukrainian children ages 8 to 17 have been taken. Investigators found evidence of reeducation at 62% of sites, and military training at 19%.

The study also says there are signs that roughly a quarter of the facilities have been expanded since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. The network stretches more than 3,500 miles from the Black Sea to Siberia and includes two new cadet schools and even a monastery. The report alleges about half of the locations are directly managed by Russian federal or local authorities.

Investigators used tools including open-source information and high-resolution satellite images to identify the sites and specifics such as firing ranges and trenches.

It’s still unclear how many Ukrainian children are in this network. Ukraine’s government said it has verified that at least 19,500 children are missing since 2022 while the Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab estimates that the number could be up to 35,000.

Raymond said he has heard from several European officials who are “horrified” by the report and said it could be a “turning point because, for Europe, it shows in high relief how big this is as a system and that it’s Ukraine now, but it could be other countries next.”

Ukraine insists that the return of the children must be part of any peace deal with Russia. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and his commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, for the alleged unlawful deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia, calling it a war crime.

Russia does not recognize the ICC and dismiss the charges. The Russian government has not commented on the latest research by the Yale lab. But in response to previous accusations, Russian authorities have said they were saving children from the front line, not abducting them, and insisted the numbers of children transferred to Russia were inflated.

Last week, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said he planned to hold a “high-level event” related to Ukrainian children missing in Russia during the meeting of the U.N. General Assembly later this month.

Meanwhile, the Yale Humanitarian Research Lab is facing an uncertain future after the Trump administration canceled Conflict Observatory, a State Department-funded program that documents evidence of war crimes in Ukraine and Sudan. The Yale lab was part of that program. Its work has now been extended until January after a flurry of small, private donations from groups including evangelical organizations and the Ukrainian diaspora.

An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine — to play pretend — has long been thought to be unique to humans. A new study suggests one of our closest living relatives can do it too.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

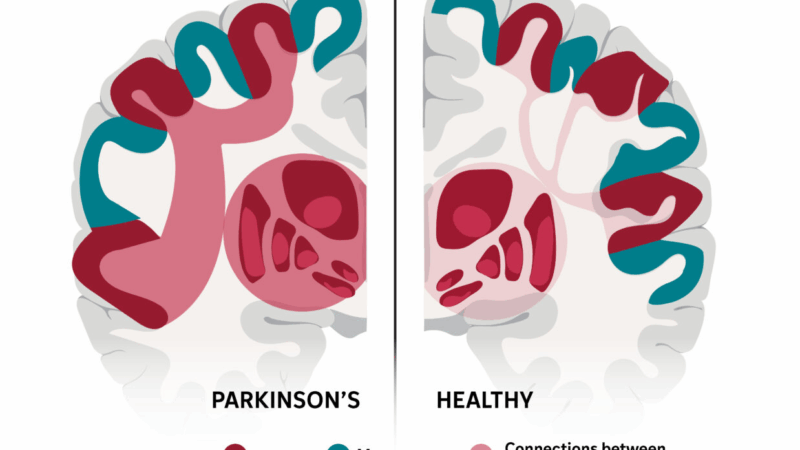

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.

Immigration officials to testify before House as DHS funding deadline approaches

Congressional Democrats have a list of demands to reform Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But tensions between the two parties are high and the timeline is short – the stopgap bill funding DHS runs out Friday.

How the use of AI and ‘deepfakes’ play a role in the search for Nancy Guthrie

As artificial intelligence becomes more advanced and commonplace, it can be difficult to know what's real and what's not, which has complicated the search for Nancy Guthrie, according to law enforcement. But just how difficult is it?