Reversing peanut advice prevented tens of thousands of allergy cases, researchers say

For years, parents were told not to expose their babies to peanuts, to prevent a potentially dangerous allergy. But 10 years ago, a landmark study found the opposite to be true, stating that if babies consume peanut products at an early age, they were far less likely to become allergic to them.

Health experts quickly took notice — and the resulting reversal in pediatric guidance has helped to push peanuts out of the No. 1 spot as the cause of food allergy for children under 3 in the U.S., according to a new study published in the peer-reviewed journal Pediatrics.

“Early allergen introduction works,” Dr. David Hill, who led the study, tells NPR. “For the first time in recent history, it seems like we’re starting to put a brake pedal on the epidemic of food allergy in this country.”

Growing concerns over food allergies have reshaped parts of Americans’ diet, from schools and camps banning peanut butter in sandwiches to airlines nixing once-ubiquitous bags of salted nuts. In 2015, The New England Journal of Medicine referenced a quadrupling of peanut allergy’s prevalence in U.S. children, citing growth from 0.4% in 1997 to more than 2% in 2010.

But when U.S. health guidance changed in 2015 and 2017, so did that trend, according to Hill, a pediatric allergist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania.

“There was a 43% reduction in peanut allergy prevalence,” Hill says, “and a 36% reduction in any food allergy prevalence.”

He estimates that the changed guidelines have prevented peanut allergies in at least 40,000 children in the last decade.

The tipping point in peanut allergy prevention dates to 2015, when research was published that aimed to solve a puzzle: Why was peanut allergy 10 times higher among Jewish children in the U.K. than among Israeli children with similar ancestry? Researchers noted that while British and U.S. parents kept their babies away from peanut products, many Israeli parents routinely fed their infants a puffy peanut snack called Bamba.

The revised recommendations, including in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, calls for introducing infants deemed at high risk for peanut allergy to foods containing peanuts as early as 4 to 6 months, in line with advice published in 2017 by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Hill and his colleagues looked at the rate of food allergy in young children before and after the revised guidelines for peanuts and other allergens were published. They did that by analyzing the health data of more than 120,000 children in the U.S. using records from dozens of different pediatric practices.

Dr. Corinne Keet, a professor of pediatrics at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who works in the epidemiology of food allergy, says she finds the study interesting, even if she’s cautious about reading too much into it. She wasn’t involved in the research.

“I’m a little bit surprised by these findings because I might have expected that we might have more diagnoses just because people were thinking about allergies more” in the past decade, she says.

Part of the reason for her caution, Keet says, is that her own research has found families haven’t been fully implementing the new guidelines, in many cases due to fear that exposing an infant to peanut products might also endanger a sibling or parent who’s allergic.

Keet also says it’s simply difficult to conduct a high-quality study about food allergy prevalence. She notes that the influential 2015 study, called LEAP (Learning Early about Peanut Allergy), produced definitive results by conducting a large clinical trial following hundreds of young kids over time.

Hill and his colleagues acknowledge that their study has limitations, such as relying on diagnostic codes — which aren’t necessarily equivalent to actual allergy rates. Their data also does not include information about children’s eating habits.

Still, he sees the study as another positive sign that a strategic shift is helping children. The benefits are far-reaching, he adds, because many peanut allergies are a lifetime condition.

“It’s highly persistent,” Hill says. “Only about 10% of kids who develop a peanut allergy will outgrow that peanut allergy.”

The CIA World Factbook is dead. Here’s how I came to love it

The Factbook survived the Cold War and became a hit online. It mixed quirky cultural notes and trivia with maps, data, and photos taken by CIA officers. But it was discontinued this week.

Trump promised a crypto revolution. So why is bitcoin crashing?

Trump got elected promising to usher in a crypto revolution. More than a year later, bitcoin's price has come tumbling down. What happened?

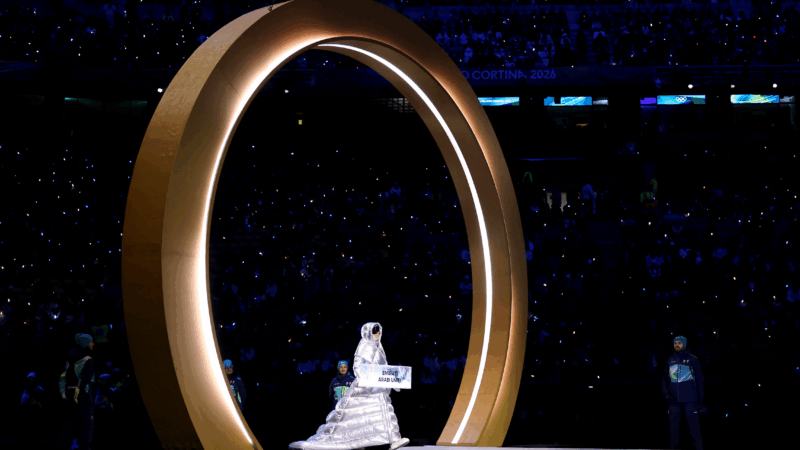

Mariah Carey, coffee makers and other highlights from the Olympic opening ceremony

NPR reporters at the Milan opening ceremony layered up and took notes.

Trump’s harsh immigration tactics are taking a political hit

President Trump's popularity on one of his political strengths is in jeopardy.

A drop in CDC health alerts leaves doctors ‘flying blind’

Doctors and public health officials are concerned about the drop in health alerts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since President Trump returned for a second term.

Photos: Highlights from the Winter Olympics opening ceremony

Athletes from around the world attended the 2026 Winter Olympics opening ceremony in Milan.