Primate pet ownership fuels a brutal industry. This bill could slow it down

On a recent day at the Oakland Zoo’s animal hospital, across the bay from San Francisco, an endangered Mexican spider monkey leaps onto tree branches, climbs across platforms and swings on ropes in a large kennel-turned-primate playground.

Named Violeta by hospital staff, the monkey — who’s about 18 months old — was poached from the wild and smuggled into California, where it’s illegal to keep primates as pets.

Violeta came to the zoo in May after her owner surrendered her during a drug bust. For nearly two months, handlers have been teaching her how to behave like a monkey.

“We dedicate hours a day to just sitting with her, socializing, grooming, teaching her how to play correctly and interact with people in a peaceful manner,” says Amber Foley, lead hospital keeper.

If all goes well, Foley says, Violeta will be able to live out her life in a troop with other spider monkeys.

But for most pet primates in the United States, a life of chronic stress, malnutrition and illness is far more likely, despite the best intentions of private owners, says Colleen Kinzley, vice president of animal care, conservation and research at the Oakland Zoo.

Kinzley says any time a monkey is living with a human rather than with its kind, “that monkey is suffering terribly because it doesn’t have its family and it doesn’t have the opportunity to behave as a monkey.”

It’s a problem fueled by social media influencers, popular television shows and films that romanticize life with these charismatic animals, Kinzley says. That in turn helps feed a brutal pet trade that starts with the killing of countless animals as members of the family troop try to protect babies from poachers.

“What happens is a number of adults are shot out of the trees in order for poachers to get hold of the babies — literally rip the babies out of the arms of the dead and dying mothers,” Kinzley says.

An “abnormal” life

California is among the states with total bans on pet primate ownership. Others have partial bans. But in some states it remains legal for people to keep and breed them — something the proposed federal Captive Primate Safety Act is aiming to change.

If passed, the bill would make private ownership and breeding of these animals illegal in all 50 states, where zoo officials and animal welfare groups say most live in unsuitable conditions — many without ever seeing another primate.

“It’s completely abnormal for them,” says Dr. Andrea Goodnight, an Oakland Zoo veterinarian. “[The primate] has no idea what to do socially, how to function — so you can imagine the level of stress and anxiety that brings to these animals.”

Many of the stolen infants that survive the poaching raids die during the smuggling operations. Others, she says, survive trafficking only to die from malnutrition or other illnesses before their first birthday.

“Some of these animals are so traumatized that they’ll just huddle in a corner,” says Goodnight. “They won’t interact, they won’t eat and they can literally starve themselves to death because they’re just too scared.”

She says dietary deficiencies are common among the primates the Oakland Zoo has taken into its rescue program.

“These infants are still very dependent on mom, they’re nursing, they’re getting mom’s milk,” she says.

Human food, she says, is very different from their diet in the wild and often results in captive primates suffering serious calcium deficiencies.

“And then they can have what are called pathologic fractures,” says Goodnight. “So they literally will walk and break their legs.”

For those who make it to sexual maturity — about 4 years of age — life often gets exponentially worse.

“As these animals grow and become more sexually mature they become super dangerous and people aren’t able to handle them,” she says. That, she adds, is when private owners may find themselves wondering: “‘Well, what do I do with this animal?'”

At that point there are few options beyond caging them for life or euthanizing them, says Kinzley.

“If they end up coming back to a zoo or sanctuary as adults, often they are so psychologically damaged it’s difficult if not impossible to get them back in a social group,” she says.

Yet, she says, it’s easy to see the appeal of these humanlike animals — especially the babies.

“People get so attached because these babies bond to them and often it’s people who love animals [who have them],” she says. “So we really try to get the word out to people who love animals (that) it’s just absolutely the worst thing.”

A plan to protect primates

Spider monkeys, like Violeta, are now among the most-trafficked animals and are listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

A coalition of zoos and animal welfare groups say passage of the Captive Primate Safety Act, along with public education, is key to protecting primates worldwide.

For now, the bill remains stuck in the House Committee on Natural Resources, as committee Chairman Bruce Westerman, R-Ark., has not scheduled it for an initial debate. The Oakland Zoo, along with a coalition of other zoos and animal welfare organizations, is now lobbying lawmakers for support. Westerman’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

In a statement, Congressman Mike Quigley, D-Ill., who introduced the bill in early May, reiterated his “commitment to ensuring we pass this legislation and end the captive primate trade.”

While the bill has stalled for now, Violeta’s life is finally gaining traction.

After nearly two months of socialization with handlers — as well as a healthy diet that included a calcium-enriched formula to minimize the likelihood of pathologic bony fractures — the little monkey has been given a second chance for a more natural existence.

Late last month, Violeta left the Oakland Zoo hospital to try out life with a troop of spider monkeys at a different zoo, the name of which officials are withholding until the legal case involving her surrender concludes.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The demand for pet primates in the U.S. fuels a brutal underground market. But a new bill in Congress aims to change that by creating a national ban on privately owning and breeding these animals. Stephanie O’Neill has this story.

STEPHANIE O’NEILL, BYLINE: Here at the Oakland Zoo’s veterinary hospital, across the Bay from San Francisco, an endangered Mexican spider monkey leaps onto tree branches and climbs ropes in a large kennel turned into a primate playground. Her name is Violeta, and she issues these spider monkey greetings to a visitor.

(SOUNDBITE OF MONKEY CHATTERING)

O’NEILL: The young monkey, who’s about 18 months old, was poached from the wild and smuggled into California, where it’s illegal to keep primates as pets. In May, after her owner surrendered her during a drug bust, Violeta came to the zoo. And for nearly two months, handlers have been teaching her how to act like a monkey. Amber Foley is a keeper at the zoo.

AMBER FOLEY: We dedicate hours a day to just spending time sitting with her, socializing, grooming, teaching her how to play correctly and interact in a peaceful manner.

O’NEILL: The goal, she says, is to socialize Violeta well enough so she can live out her life at a zoo or sanctuary with her own kind. But for most pet primates in the United States, a life of chronic stress, malnutrition and illness is far more likely, says Colleen Kinzley.

COLLEEN KINZLEY: Anytime you see a spider monkey, a monkey, with a human, the monkey is suffering terribly because it doesn’t have its family. And it doesn’t have the opportunity, you know, to behave as a monkey.

O’NEILL: Kinzley is vice president of animal care, conservation and research at the Oakland Zoo. She says social media influencers, popular TV shows and films romanticize life with primates, escalating demand. This fuels a brutal trade, one in which countless animals are killed while trying to protect babies from poachers.

KINZLEY: What happens is a number of adults are shot out of the trees in order for the poachers to get hold of the babies, literally rip the babies out of the arms of the dead and dying mothers.

O’NEILL: Yet many states still allow people to keep them as pets, something the proposed Federal Captive Primate Safety Act is aiming to change. If passed, it would ban primate pet ownership in all 50 states. Dr. Andrea Goodnight is a veterinarian at the Oakland Zoo who says keeping primates as private pets is bad for their mental and physical health.

ANDREA GOODNIGHT: It’s completely abnormal for them. It has no idea what to do socially, how to function, so you can imagine the level of stress and anxiety that brings to these animals.

O’NEILL: Many of the stolen infants who survive the poaching raids die during smuggling operations. Others, Goodnight says, survive the trafficking only to die from malnutrition or other illnesses before their first birthday.

GOODNIGHT: Some of these animals are so traumatized that they’ll just huddle in a corner. And they won’t come out, they won’t interact, they won’t eat. And they can literally starve themselves to death because they’re just too scared.

O’NEILL: For those who make it to maturity, about four years of age, she says life often gets exponentially worse.

GOODNIGHT: As these animals grow and become more sexually mature, then they become super dangerous, and people aren’t able to handle them. And then a lot of times, then you’re stuck with this, well, what do I do with this animal?

O’NEILL: And at that point, says Kinzley, there are few options beyond caging them for life or euthanizing them.

KINZLEY: Coming to a zoo or a sanctuary as adults, often they’re so psychologically damaged, you know, it’s difficult if not impossible to get them back in a social group.

O’NEILL: Colleen Kinzley says passage of the Captive Primate Safety Act and educating the public are key to protecting these animals. But since its May 5 introduction, the bill has remained stalled in the House Committee on Natural Resources, which has yet to bring it up for debate. Violeta’s life, on the other hand, is gaining traction. Late last month, she left the Oakland Zoo hospital and is now trying out a new life with a family of spider monkeys.

(SOUNDBITE OF MONKEY CHATTERING)

O’NEILL: For NPR News, I’m Stephanie O’Neill in Oakland, California.

(SOUNDBITE OF I.AM.TRU.STARR SONG, “(ETC.)”)

Where patients live matters for access to gene therapy

Gene therapies have the potential to cure some diseases, but they are extraordinarily expensive. Location can also be a big hurdle for patients seeking this specialized care.

Democrats tap Spanberger and Padilla to respond to State of the Union

Virginia Gov. Abigail Spanberger will deliver Democrats' response on Tuesday following President Trump's State of the Union address.

Is the YIMBY movement doomed?

For decades, rising home prices have been an engine for middle-class wealth. Now a growing movement wants to slow — or even reverse — that trend. Are the politics around new housing development inherently stacked against them?

What you need to know as Russia’s full-scale war on Ukraine enters its 5th year

Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine four years ago, and the fighting continues. Here's a look at where the war stands today.

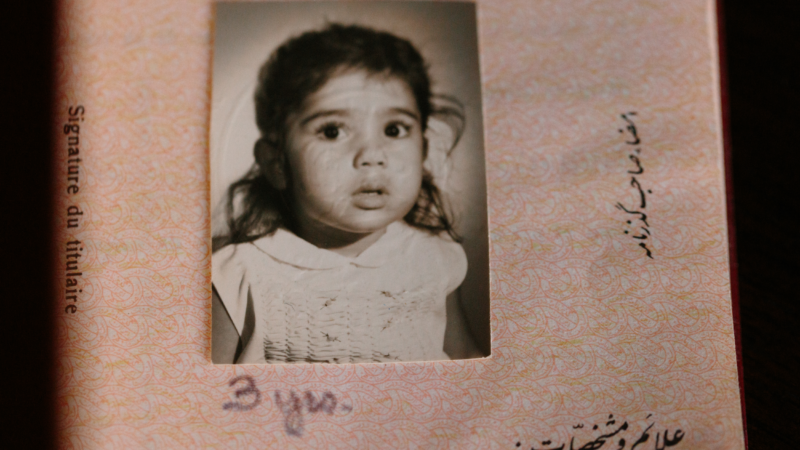

A U.S. veteran adopted an orphan from Iran. Decades later, ICE is trying to deport her

The woman has no criminal record and is unsure what prompted the threat of removal. She fears being deported to Iran given her father's military service and her Christian faith.

What you need to know about tonight’s State of the Union address

The prime-time address is a chance for the president to tout his record ahead of this year's midterm elections. But it comes at a moment when Trump has seen his agenda complicated on multiple fronts.