Photos: How torn pictures and trusted herbs create healing in Colombia

Stitching sutures is one way doctors treat wounds.

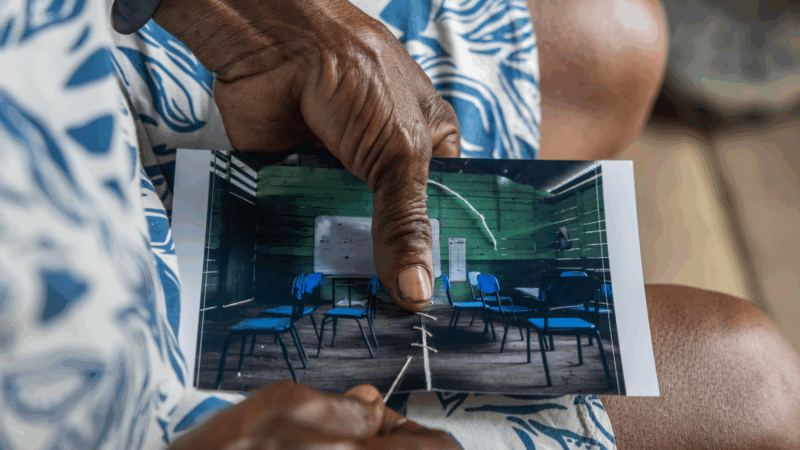

But now there’s another kind of stitching to heal psychic wounds: tearing up and then sewing back together photographs of loved ones and homes. That’s one of the rituals devised in the remote area of Alto Baudó in the western region of Colombia, where feuds between armed rebel and criminal groups have terrorized the population for years.

The photo stitching is part of a two-year project conceived of by Doctors Without Borders, working with community healers and midwives from 2022 to 2024. The goal has been to create rituals to help manage the anxiety, depression and other mental health risks posed by the area’s widespread violence.

The rending and mending of photos is a metaphor for healing, according to Colombian photographer Fernanda Pineda, who documented the project. Other rituals to reclaim memories of once peaceful places beset by violence include the use of fragrant herbs and leaves the healers traditionally employ to reduce pain and bring comfort.

The organization also brought in medical teams to train 48 people in the community as health workers and health promoters to ensure the availability of basic medical services. That’s essential because the isolated location means that it may take two to three days to reach a health center or hospital.

As Santiago Valenzuela, a communication manager for Doctors Without Borders from Colombia, said, “We created a dialogue between Western medicine and local healers.”

Seven healers and the rituals they conceived and used during the course of the project are chronicled in Pineda’s photography series, Riografias del Baudó. It’s on view at the annual Photoville Festival in Brooklyn, New York, where a sprawling array of shipping containers are converted into mini-photo galleries through June 22. The project’s title uses the Spanish word for river in a play on the Spanish word for photograph, fotografía.

“We chose to include Riografías: Women Healers of Alto Baudó because [the exhibit] exemplifies the power of visual storytelling to illuminate overlooked global health crises and the extraordinary resilience of women,” says Photoville creative director and co-founder Sam Barzilay, noting that the project depicts women as “agents of change, resilience and healing in the face of systemic neglect — stories we felt urgently needed to be seen and acknowledged.”

About 14,000 people, many of them of African descent or indigenous Embera, live in the approximately 130 communities in this rainforest area bordered by the Baudò River, Pineda said. Thousands of people have fled the region to avoid confrontations between armed groups that sometimes forcibly try to recruit them. The use of land mines by the combatants poses a constant danger. As a result of these threats, many of those who remain confine themselves for safety, unable to work or attend school.

People of all ages gather at the river in the above photograph, with family bungalow houses and immense greenery receding into the distance. “This shows their community,” Pineda says. “It’s morning, you see intimate moments with one woman holding a baby, people doing their wash, everyone is there.”

The kids at the river play with pails and balls and, as in this photo, a small canoe seen from the back. This young boy may have painted his face as a symbol of protection, Pineda said.

The peaceful river scene belies the stress that the community has suffered. “Chachajo is sick with fears. I am sure of that, because I, myself, live with that sickness,” says traditional healer Carmen Fidela Mena,

She has learned medical techniques as well. “Many years ago, a physician from Doctors Without Borders taught me how to suture wounds,” Mena says. “Sometimes, I don’t have the tools, like the needles and thread, so I have to use what I have: black thread and a well-disinfected sewing needle. And when there´s no sewing thread, we´ve had to use dental floss.”

This photo is overlain with dried, preserved leaves. Healer Teolinda Castro, from the community of Mojaudó, is quoted as saying: “At the Mojaudó school, there was a confrontation that left bullet holes in the walls and ceiling. The resucito plant is used to cure pain. If my child tells me ‘Oh, mom, my head hurts,’ I get some resucito and wash their little head with it. The day [the confrontation at the] school happened, I got under the bed because I thought: ‘Am I going to die? If my blood pressure rises, I die here.’ So I stayed still.”

These new rituals do bring a sense of hope, the healers say — even as the fighting continues.

Diane Cole writes for many publications, including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. She is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges. Her website is DianeJoyceCole.com

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

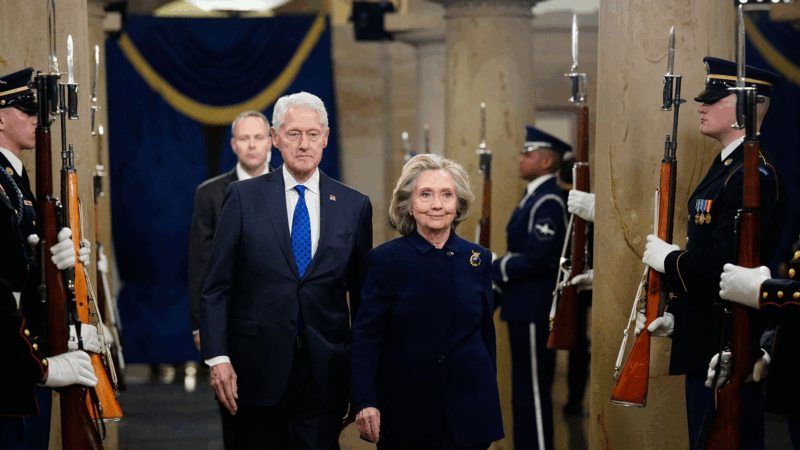

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

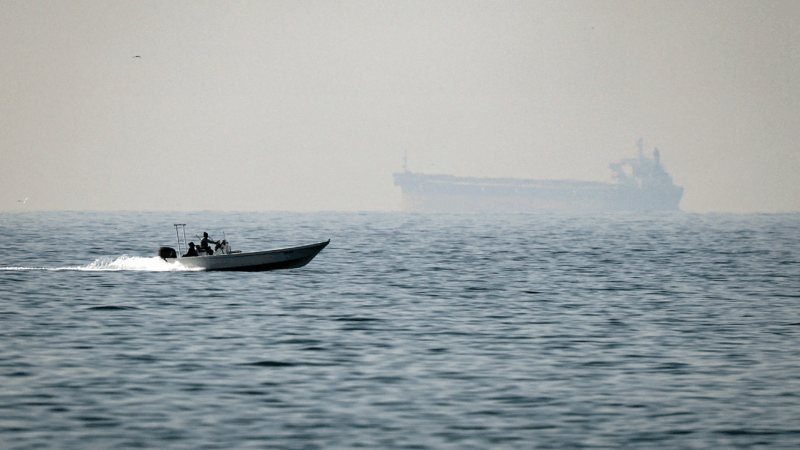

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.

‘Hamnet’ star Jessie Buckley looks for the ‘shadowy bits’ of her characters

Buckley has been nominated for a best actress Oscar for her portrayal of William Shakespeare's wife in Hamnet. The film "brought me into this next chapter of my life as a mother," Buckley says.

How, who, and why: NPR flips its famous letters to defend the right to be curious

NPR is standing up for the public's right to ask hard questions in a national campaign dubbed "For your right to be curious." At NPR's headquarters, on billboards in New York City, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., and across social media, NPR's three iconic letters transform into "how," "who," and "why" — a bold declaration of its commitment to fight for Americans' right to ask questions both big and small.

Oil prices surge, but no panic yet, as Iran war continues

Global oil prices are in the high $70s as traffic through Strait of Hormuz comes to a halt. Some analysts have warned they could top $100 a barrel if the stoppage is prolonged.