New Orleans brings back the house call, sending nurses to visit newborns and moms

When Lisa Bonfield gave birth to her daughter Adele in late November, she was thrust into the new world of parenting, and faced an onslaught of challenges and skills she had to learn: breastfeeding, diapering, sleep routines, colic and crying and all the little warning signs that something could be wrong with the baby.

But unlike parents in most of the U.S., she had a kind of extra help that used to be much more common: house calls.

Bonfield’s daughter Adele was only a few weeks old when a registered nurse showed up at her door on Dec. 10 to check on them and offer hands-on help and advice.

As a city resident who had just given birth, she was eligible for up to three of these home visits from Family Connects New Orleans, a program of the city health department.

She didn’t need to feed and change the baby, and pack everything up for a car trip to the pediatrician or a clinic.

It was a relief; Bonfield was exhausted, and was still trying to figure out how to use the infant car seat.

“Everything is so abstract before you have a baby,” said Bonfield. “You are going to have questions you never even thought about.”

Bonfield lives in Louisiana, one of the worst-performing states when it comes to health outcomes of mothers and new babies. Now, New Orleans is trying to catch health issues early — and get families off to an easier start — by adding extra health visits during the crucial first months of life.

The hope is that health outcomes can be improved by returning to the old-fashioned medical practice of bringing the nurse to the family.

The Family Connects model has been tried in communities across 20 states. It began in Durham, North Carolina in 2008, as a partnership with Duke University. In 2023, New Orleans’ health director, Dr. Jennifer Avegno, helped launch a version of the program locally.

Avegno was concerned by Louisiana’s particularly grim statistics for maternal and infant health.

The state has some of the highest rates of pre-term births, unnecessary C-sections, and maternal and infant deaths, according to the March of Dimes. A recent analysis from the United Health Foundation found Louisiana was the “least healthy” state for women and children.

“We got to do some real things, real differently, unless you like being number 50 all the time,” Avegno said.

Bringing back the home visits of the past

The home visits are free, available to any person who has just given birth in a New Orleans hospital, no matter their insurance status or income level.

Avegno describes the home visits as going “back to the future,” replicating a practice that was far more common a hundred years ago.

“There is no more critical time and vulnerable time than right at birth and in the few weeks to months following birth,” Avegno said.

The nurses arrive with diaper bags filled with newborn essentials, from diapers to nipple cream.

They weigh and measure and examine the babies, and check in with the mothers about their health and well-being. They offer referrals to other programs across the city.

They ask if the family has enough food, and whether there are guns in the house and how they’re stored, said Avegno.

In Bonfield’s case, the nurse stayed for over two hours. Bonfield especially liked their conversation about how to store breastmilk safely.

“I’ve never felt so well taken care of and listened to,” she said.

A reproductive health care intervention with broad support

Louisiana has struggled for a long time with poor maternal and infant health outcomes, but the problem has been complicated by the state’s strict abortion ban.

The 2022 law led to risky medical delays and unnecessary surgeries in obstetrical care, and confusion among doctors about what’s allowed in ending dangerous pregnancies or treating miscarriages.

Avegno opposes the state’s abortion policies, believing they are harmful for women’s health. But she says that Family Connects offers other ways to preserve and expand care for women’s health. For example, the visiting nurse can check in with the mother about if she needs help with birth control.

“We can’t give them abortion access,” she said. “That’s not the goal of this program, and that wouldn’t be possible anyway, but we can make sure they’re healthy and understand what their options are for reproductive health care.”

Abortion politics aside, the postpartum home visits seem to have bipartisan support in Louisiana, and state lawmakers want to expand access.

In 2025, the Republican-dominated legislature passed a law requiring private insurance plans to cover the visits.

The new law is another way that Louisiana officials can be “pro-life,” said state Rep. Mike Bayham (R), an abortion opponent who sponsored the new law.

“One of the slings used against advocates against abortion is that we’re pro-birth, and not truly pro-life,” Bayham said, “And this bill is proof that we care about the overall well-being of our mothers and our newborns.”

Improving health and help for postpartum depression

Two years in, there are already promising signs that the program is improving health.

Early data analyzed by researchers at Tulane University found that families who got the visits were more likely to stick to the recommended schedule of pediatric and postpartum checkups. Moms and babies were also less likely to need hospitalization, and overall healthcare spending was down among families insured by Medicaid.

Research on Family Connects programs elsewhere in the country has found similar results. In North Carolina, one study showed it reduced E-R visits by 50% in the year before a baby turned one.

But the statistic that most excited Avegno related to the program’s role in screening mothers for postpartum depression.

The visiting nurses are helping spot more cases of postpartum depression, earlier, so that new moms can get treatment. About 10% of moms participating in the program were eventually diagnosed with postpartum depression, compared to 6% of moms who did not get the visits.

Timely diagnosis is important to prevent depression symptoms from worsening, or leading to more severe outcomes such suicidal thoughts, thoughts of harming the baby, or problems bonding with their newborn.

Lizzie Frederick was one of the mothers whose postpartum symptoms were caught early by a visiting nurse.

When she was pregnant, she and her husband took all the childbirth and new baby classes they could. They hired a doula to help with the birth. But Frederick still wasn’t prepared for the stresses of the postpartum period, she said.

“I don’t think there are enough classes out there to prepare you for all the different scenarios,” said Frederick.

When her son James was born in May, he had trouble breastfeeding. He was only sleeping for 90-minute stretches at night.

When the nurse arrived for the first visit a few weeks later, Frederick was busy trying to feed James. But the nurse reassured her that there was no rush. She could wait.

“I am here to support you and take care of you,” Frederick recalled the nurse saying.

The nurse weighed James, and Frederick was relieved to learn he was gaining weight. But for most of the visit, the nurse focused on Frederick’s needs. She was exhausted, anxious, and had started hearing what she called phantom cries.

The nurse walked her through a mental health questionnaire. Then she recommended that Frederick see a counsellor and consider attending group therapy sessions for perinatal women.

Frederick followed up on these suggestions, and was eventually diagnosed with postpartum depression.

“I think that I would have felt a lot more alone if I hadn’t had this visit, and struggled in other ways without the resources that the nurse provided,” Frederick said.

Home visits save money

Melissa Evans, an assistant professor at Tulane’s School of Public Health, helped interview over 90 participating families.

“It was overwhelmingly positive experiences,” she said. “This is like a gold standard public health project, in my opinion.”

To operate Family Connects costs the city about $1.5 million a year, or $700 per birth, according to Avegno.

But the program also has the potential to save money: Research on North Carolina’s program found that every $1 invested in the program saved $3.17 in healthcare billing before the child turned two.

That’s another reason to require the visits statewide, according to state Rep. Bayham.

“The nurses and medical practitioners will be able to monitor potential problems on the front end, so that they could be handled without a trip to the emergency room or something even more drastic,” he said.

Dr. Avegno is advocating that the program be included in Louisiana’s Medicaid program, since more than 60% of births are covered by Medicaid. A recent legislative report made the same recommendation.

This story comes from NPR’s health reporting partnership with WWNO and KFF Health News.

Transcript:

SACHA PFEIFFER, HOST:

For a long time, Louisiana has struggled with the health of new mothers and babies. Now New Orleans is tackling that problem with a return to an old-fashioned medical practice – the house call. Rosemary Westwood at member station WWNO explains.

ROSEMARY WESTWOOD, BYLINE: Lisa Bonfield is cradling her new baby girl on the couch. She’s named Adele (ph), and she has the hiccups.

LISA BONFIELD: I think it’s the – she hates the hiccups.

WESTWOOD: Oh, who would like them (laughter)?

BONFIELD: She used to get them all the time in my stomach, and it’s just funny that she gets them now. It’s just – I know she’s mine.

WESTWOOD: Lisa is 43 and a single mom. Adele was born in late November. Soon after, the nurse dropped by. First, they went over Lisa’s health.

BONFIELD: Then she did a visit on the baby. She checked her heartbeat, her lungs.

WESTWOOD: Family Connects New Orleans provides up to three home visits for new families in the city, and they’re free. No need to feed and change the baby and pack everything up for the bus or the car.

BONFIELD: When you’re still learning how the heck a car seat works.

WESTWOOD: Instead, Bonfield could relax in her own living room. When the nurse arrived, she had extra diapers and cream and tips about breastfeeding and what to do when the baby just won’t stop crying. Lizzie Frederick also got a home visit, and she was surprised how much she needed it. She had taken all the childbirth classes and even had a doula, but after James (ph) arrived in May…

LIZZIE FREDERICK: I was not prepared for postpartum. I don’t think that there are enough classes out there to prepare you for all the different scenarios.

WESTWOOD: Breastfeeding was a struggle, and James wasn’t a great sleeper.

FREDERICK: He was sleeping roughly for 90 minutes at a time and then waking up.

WESTWOOD: When the nurse arrived for the home visit, Frederick was busy feeding James. But the nurse said, no problem. She could wait.

FREDERICK: You are a new mom. Like, do what you need to do. I’m here to support you and take care of you.

WESTWOOD: Afterwards, the nurse weighed James. To Frederick’s relief, he was gaining weight. Then they talked about her. Frederick was exhausted, anxious and hearing phantom cries. The nurse walked her through a mental health questionnaire. Then she recommended a counselor and group sessions for perinatal women.

FREDERICK: I think that I would have felt a lot more alone if I hadn’t had this visit.

WESTWOOD: Frederick was later diagnosed with postpartum depression.

Dr. Jennifer Avegno is the director of the New Orleans Health Department. She launched Family Connects two years ago.

JENNIFER AVEGNO: There is no more critical time and vulnerable time than sort of right at birth and in the few weeks to months following birth.

WESTWOOD: These kinds of postpartum home visits are happening in other places. Research on North Carolina’s program showed it cut ER visits for newborns in half. In New Orleans, the nurses are helping spot more cases of postpartum depression earlier so that new moms can get treatment. Frederick says that was crucial.

FREDERICK: The resources that Family Connect provided really allowed me to find a community of people where I could talk about my struggles and hear tips and not feel judged and just come as I am.

WESTWOOD: The nurses are up against some grim statistics. The state has among the highest rates of infant and maternal death. A recent report called Louisiana the least healthy state for women and children. Dr. Avegno says that’s unacceptable.

AVEGNO: We got to do some real things real differently unless you like being No. 50 all the time.

WESTWOOD: This year, state legislators passed a new law that will require private insurance to cover these home visits throughout Louisiana. Republican Representative Mike Bayham authored the new law. Given that Louisiana now has one of the country’s strictest abortion bans, Bayham says these efforts are another way Louisiana can protect life.

MIKE BAYHAM: One of the slings used against advocates against abortion is that we’re pro-birth and not truly pro-life. And this bill is proof that we are – we care about the overall well-being of our mothers and our newborns.

WESTWOOD: Bayham says the home visits will reduce trips to the hospital, and that will bring down health care costs. But Dr. Avegno wants more. Since 60% of births here are covered by Medicaid, she’s pushing state officials to add the home visits to Medicaid, too.

For NPR News, I’m Rosemary Westwood in New Orleans.

PFEIFFER: This story comes from NPR’s partnership with WWNO and KFF Health News.

AI brings Supreme Court decisions to life

Like it or not, the justices are about to see AI versions of themselves, speaking words that they spoke in court but that were not heard contemporaneously by anyone except those in the courtroom.

The airspace around El Paso is open again. Why it closed is in dispute

The Federal Aviation Administration abruptly closed the airspace around El Paso, only to reopen it hours later. The bizarre episode pointed to a lack of coordination between the FAA and the Pentagon.

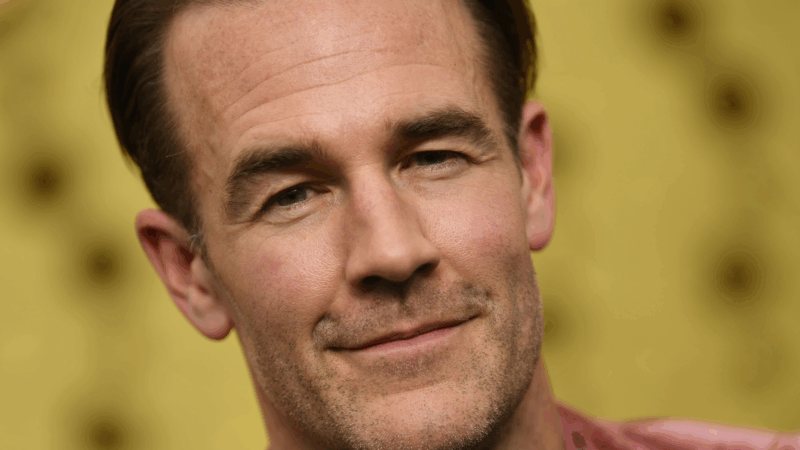

‘Dawson’s Creek’ star James Van Der Beek has died at 48

Van Der Beek played Dawson Leery on the hit show Dawson's Creek. He announced his colon cancer diagnosis in 2024.

A Jan. 6 rioter pardoned by Trump was convicted of sexually abusing children

A handyman from Florida who received a pardon from President Trump for storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, was convicted on state charges of child sex abuse and exposing himself to a child.

A country-pop newcomer’s debut is your reinvention album of 2026

August Ponthier's Everywhere Isn't Texas is as much a fully realized introduction as a complete revival. Its an existential debut that asks: How, exactly, does the artist fit in here?

U.S. unexpectedly adds 130,000 jobs in January after a weak 2025

U.S. employers added 130,000 jobs in January as the unemployment rate dipped to 4.3% from 4.4% in December. Annual revisions show that job growth last year was far weaker than initially reported.