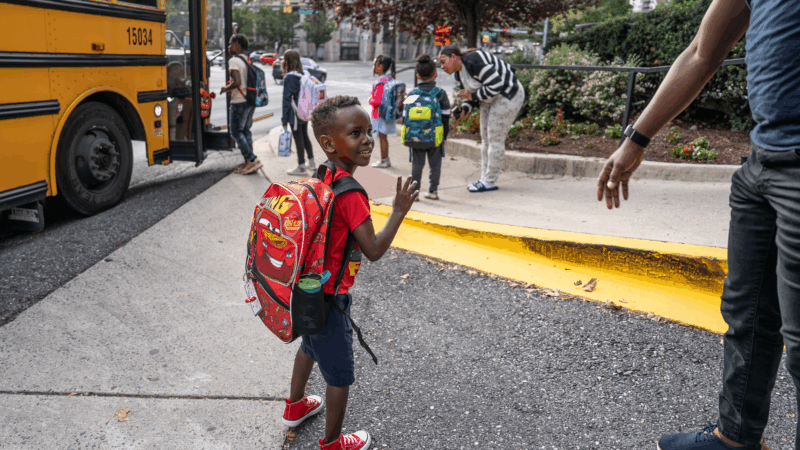

My son loved his first day of kindergarten. It brings up my own bittersweet memories

Millions of children across the United States are stepping into kindergarten for the first time. My son is one of them.

It’s emotional for any parent — watching your child take those steps into the world, into routine, into independence. For immigrant parents like my wife and me, it was overwhelming.

My son, Russell Siima, started the first year of his primary education in a public school in Montgomery County, Md. My wife and I dropped my son off, his baby brother in tow. We waved goodbye and encouraged him to be brave. His classroom has colorful posters, smart boards and cozy reading corners filled with books and comfy swivel chairs. Each child has a cubby with their name on it for storing the school supplies tucked into their backpacks.

Like every parent, I hope my child likes — no, make that loves — their teacher. That they feel welcome in school and enjoy their first step to the many years of learning ahead.

But as my son marks this milestone, I have mixed emotions. I am so excited about his schooling. Then I flash back to my own first day, in my home country of Uganda. It was a very different experience.

When I was 4, my mother sent me to another county in rural southwestern Uganda — to live with my uncle’s family, where school options were better — to begin my education in what we called “church school.” Used for Sunday mass, the building itself was a long, rectangular room with a dirt floor, iron sheet roofing, no ceiling and wooden shutters instead of glass windows. A row of concrete pillars held up the tin roof. When it rained, the noise was so deafening that classes had to pause.

On my first day at church school, my cousin Mary and her older brother walked with me the mile or so to school and dropped me off. My mother had brought me to stay with my maternal uncle’s family in a neighboring county, where school options were better. In my home county, the nearest “church school” was about 9 miles away – too great a distance for a child to walk.

I was only at that school for a year before I transferred to Katebe Primary School — the best in the county. It gave me a solid foundation for learning. But it wasn’t ideal. When I tell my American friends that our first job every morning was to sweep the classroom before we sat down, they chuckle. For me, it was serious business — it taught me to take care of the space around me, to be responsible even with very little.

Yet I dreamed of one day coming to a classroom where the only thing I had to carry was curiosity.

My dream came true in the fall of 2004. I arrived in Florida from Uganda as a 19-year-old, fresh off the plane, stepping foot into my first American classroom at Tallahassee Community College. I had been adopted by a generous Floridian couple — Russell and Cheri Rainey — who, after meeting me in Uganda and hearing about my passion for education, decided to bring me into their family. They became Mom and Dad.

I remember that first semester, wide-eyed as I walked the campus of 15,000 students, marveling at the library, the technology and the professors who deeply cared about my curiosity. I used to sit in those classrooms thinking: One day, I hope my children — indeed all kids — get to have this kind of opportunity.

I graduated top of my class, was unanimously selected to give the 2014 commencement address at the Leon Tucker Civic Center, earned a scholarship to Florida State University and, later, graduate school.

So last week, standing in a kindergarten hallway beside my wife — watching our firstborn take his first steps into formal schooling at age five — we were moved beyond words. The school had so many resources — a fully stocked library, a music room, an art room, shelves of learning materials.

In Uganda, schools with these kinds of resources are virtually inaccessible to the average child. They’re reserved for maybe two percent of the population — mostly the children of wealthy families, high-earning businesspeople or government elites.

To us, it felt like witnessing a dream we’d carried quietly for years — one we wish every child, not just our own, could one day live.

In that moment, we knew: every sacrifice we’ve made, every mile we’ve walked — literally and figuratively — had led to this. And it was worth it.

Life, sometimes, comes full circle.

This moment reminded me of something deeply personal: that showing up as a father, being present, is a quiet miracle many take for granted. I never had my dad there for school drop-off.

My father was alive during my early years but mostly absent in my life — working far from home, present only on holidays. By the time I was ten, he had died. Between 1988 and 1992, I lost both my parents and three siblings. I was part of a generation of Ugandan children left behind by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, raised by my grandmother.

On my son’s first day in kindergarten, I got to be there.

I also remembered those who made this possible — my Ugandan mother, who sent me away so I could learn; my grandmother, who raised me when no one else could; and the Raineys, whose act of kindness unlocked a future I once thought impossible. There’s a saying from Africa: One act of generosity can unlock a thousand doors. I’m living proof. And now, so is my son.

Too many children around the world don’t get this chance. Children in refugee camps, war zones and neglected communities.

I pray every child gets a first day like this — full of love, nerves, curiosity and hope. I pray that every parent, no matter where they come from, gets the chance to witness it.

Because those first steps? They’re everything.

James Kassaga Arinaitwe is Senior Director of Emerging Leaders and Public Engagement at Teach For All and co-founder and former CEO of Teach For Uganda. He lives in Silver Spring, Md., with his wife and two sons. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, NPR, Devex and Al Jazeera.

Pregnant migrant girls are being sent to a Texas shelter flagged as medically risky

Government officials and advocates for the children worry the goal is to concentrate them in Texas, where abortion is banned.

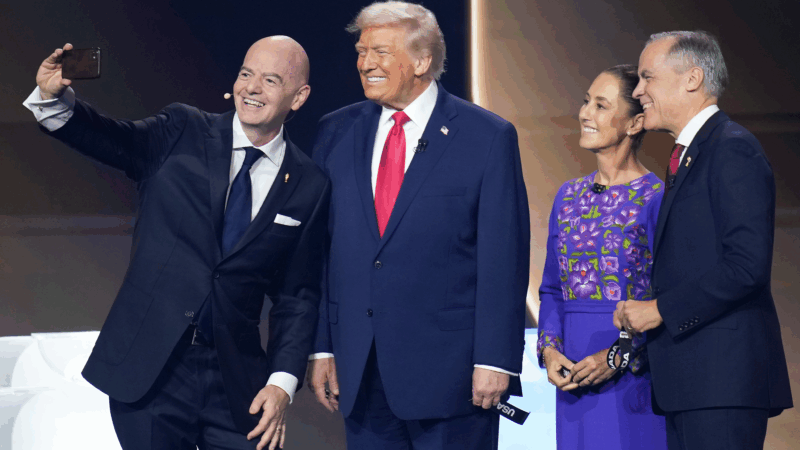

The 2026 World Cup faces big challenges with only 100 days to go

Will Iran compete? Will violence in Mexico flare up? And what about funding for host cities in the U.S.? With only 100 days left before it beings, the 2026 World Cup in North America is facing a lot of uncertainty.

A glimpse of Iran, through the eyes of its artists and journalists

Understanding one of the world's oldest civilizations can't be achieved through a single film or book. But recent works of literature, journalism, music and film by Iranians are a powerful starting point.

Mitski comes undone

She may be indie rock's queen of precisely rendered emotion, but on Mitski's latest album, Nothing's About to Happen to Me, warped perspectives, questionable motives and possible hauntings abound.

This quiet epic is the top-grossing Japanese live action film of all time

The Oscar-nominated Kokuho tells a compelling story about friendship, the weight of history and the torturous road to becoming a star in Japan's Kabuki theater.

The Live Nation trial could reshape the music industry. Here’s what you need to know

On Tuesday opening statements will begin for the federal antitrust trial against Live Nation, one of the largest entertainment companies in the world.