Muddy boots and AI are helping this threatened frog to make a comeback

It had been five years since the first of the frog eggs had been moved, carefully plucked from Mexico’s Baja Peninsula and transported by cooler to Southern California. Anny Peralta-Garcia was getting nervous.

The eggs belonged to California red-legged frogs, an amphibian that had been eaten, bulldozed and eventually pushed out of the state decades earlier. Peralta-Garcia, an Ensenada-based conservation biologist, had helped harvest fresh eggs from a pond in Baja. The efforts to move them back to the frogs’ historic range in California had been monumental — involving private landowners, federal agencies, conservation groups, helicopters and an international border.

And now, 87 more moved egg masses later, everyone was waiting to see if it worked. If the re-introduced frogs were breeding.

“We were like, okay, if frogs reach sexual maturity in two years, maybe three, maybe four, we should be seeing something,” Peralta-Garcia says. “But then, third year, fourth year, nothing.”

Finally this year, the scientists tried something new to listen in on the frogs: Artificial Intelligence. A customized AI model sifted through thousands of hours of audio recordings from the relocation sites and picked out the sound of mature male frogs calling – grunting more like – at their new location.

It was the first time the California red-legged frog had been heard in the wilds of San Diego County in 25 years, and a new egg mass soon followed.

It’s the latest example of how new technologies like AI are helping muddy-boot biologists and wildlife conservationists fight an ever-worsening extinction crisis.

“It’s been like an impossible dream since the 90’s to actually be able to go out and see wild frogs at these sites again,” says Robert Fisher, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

Here’s how it happened.

The celebrated jumping frog of Calaveras County

At about five inches in size, the California red-legged frog is the largest native frog species west of the Rocky Mountains. It used to be found in ponds and waterways, from northern Baja California, in Mexico, to above San Francisco Bay, with populations as far inland as the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

The frog’s prevalence made it a popular food source in the 1800s and for miners during the California Gold Rush, says Bennett Hardy, an amphibian ecologist at the San Diego Natural History Museum. “It was kind of the hot cuisine at the time,” he says.

The frog leaped to national fame with Mark Twain’s short story The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, which helped launch his writing career.

But the next 150-or-so years weren’t so great. Wetlands were drained for agriculture and homes. Streams were dammed, diseases struck and the American bullfrog, a fearsome predator and the largest native frog east of the Rocky Mountains, was introduced.

In 1996, the California red-legged frog was listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“It’s now occupying less than 70 percent of its historic range,” says Susan North, director of stewardship for The Nature Conservancy in California. That includes a stretch from Los Angeles to northern Baja California with zero populations.

“So that’s a 260-mile gap in the range of the species,” she says. “With a gap that size, you’re not going to have five-inch frogs re-colonizing their range naturally.”

A group was formed in the mid-2000s, including the Nature Conservancy,, and the decision was made to help bring them back. Genetic testing showed the frogs that used to live in Southern California most closely resembled remnant populations in Mexico.

“So in thinking about reintroducing frogs and bringing them back and restoring these ecosystems, it became clear we needed a Mexican source for the frogs,” says Fisher.

In Mexico, Peralta-Garcia and her nonprofit Fauna del Noroeste set to work preserving the Baja Peninsula’s last-remaining populations of red-legged frogs, restoring habitat and boosting their populations with the support of the U.S.-based groups.

Meanwhile, in Southern California, two sites with multiple water bodies were identified as suitable habitats in San Diego and Riverside counties. They were cleared of invasive, predatory bullfrogs.

In 2020, after a tangle of paperwork and permits, the first translocation took place.

“It was like planes, trains and automobiles,” Fisher says. “It was just a lot of different moving parts.”

An egg mass was moved by helicopter and car, down dirt roads and over the U.S. border to one of the prepared sites in Southern California. Others followed. The wait began.

Tasking AI to listen for frogs

The goal of a translocation, or assisted migration, is to either move a species back to a place it’s been extirpated from, or to a more suitable habitat. The latter is becoming more relevant as the climate warms and ecosystems change.

For a relocation to be successful, the moved species needs to be able to survive on its own in its new environment. It needs to be self-sustaining. And to self-sustain, the frogs needed to be breeding.

The easiest way to know if frogs are breeding is by listening for their calls, says Hardy. “When frogs are calling, most of the time, that’s the male of the species using those calls as an advertisement.”

But trying to listen out for occasional nocturnal mating calls is tedious work. “I’d love to be out there every night at these ponds, with my tent and camping and trying to listen for them, but it’s just not feasible,” he says.

So instead Hardy and the team set up a series of microphones around the relocation sites.

The microphones recorded audio from dusk to dawn, day after day, week after week, collecting thousands of hours of audio during the frog’s winter mating season.

But that led to a new problem. Hardy says they’d need an army of ears “to be able to sort through all these files and find where the frogs are.”

To help reduce the time and effort, the team partnered with outside engineers to create a custom machine learning model – similar to the popular birding app Merlin – trained to sort through the data and detect the calls of two species: the California red-legged frog and their competitor, the non-native American Bullfrog.

It wasn’t perfect at first. Hardy says that early on, the model flagged a call that it thought was a frog but was in fact a hooded merganser, a bird that’s also known as the frog duck because its mating calls sound so similar to a frog’s. But with time, they’ve been able to refine the model and are now working on a real-time alert system that will let biologists know instantaneously when a Bullfrog or red-legged frog is detected.

For Clark Winchell, a long-time muddy boot biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the technology has been revelatory.

“I spent countless hours by myself in a kayak listening for bullfrogs. It’s not the most efficient use of time,” he says. “What they’ve done with AI on this project is incredible. It’s systematic monitoring of two species.”

Using the model, earlier this winter, they were able to identify the grunts of a California red-legged frog. Soon after, a survey found a new gelatinous ball of fresh eggs near the microphone that recorded it.

North, who’d helped spearhead the effort for more than a decade, says it brought tears to her eyes. There’s still work to do, she says. There’s still a lot of gaps in the species’ historic range.

But in some parts of Southern California, for the first time in decades, she says, “We’re hearing them again.”

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

Put a microphone outside overnight in Southern California not far from the urban sprawl, and you might be surprised how much you can hear.

(SOUNDBITE OF ANIMAL HOWLING)

SUMMERS: But for scientists listening for the grunts of a federally threatened frog, all that sound is a problem. NPR’s Nate Rott has the story of how artificial intelligence is helping cut through the noise.

NATE ROTT, BYLINE: All right. Before we get to the fancy frog-finding technology part of this whole thing, there’s a pretty wild border-hopping backstory to tell about why scientists are so keen to hear these frogs.

SUSAN NORTH: The California red-legged frog is the largest native frog in the western United States.

ROTT: This is Susan North, the director of stewardship for The Nature Conservancy in California. And historically, she says, the California red-legged frog used to be found in ponds and waterways from Baja, California, all the way up through the U.S. state. They were so prolific that they were a food source for the forty-niners during the gold rush. The short story that launched Mark Twain’s writing career, “The Celebrated Jumping Frog Of Calaveras County” – a California red-legged frog. Today, though?

NORTH: Unfortunately, over the last, like, 150 years, it has really declined, and it’s now occupying less than 70% of its range.

ROTT: Habitat loss, disease, overconsumption and invasive species like bullfrogs have killed off populations, creating a 250-mile long gap in the frog’s historic range – an area where none are left, centered over Southern California.

NORTH: And with a gap that size, you know, you’re not going to have 5-inch frogs recolonizing their range naturally.

ROTT: So North and a group of other scientists and conservationists decided to help bring them back – translocating them, if you want to be technical – from a site in Mexico. Robert Fisher is a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

ROBERT FISHER: It was like “Planes, Trains and Automobiles.” It was just a lot of different moving parts.

ROTT: A paperwork and permitting nightmare, as he puts it. But in 2020, the first egg masses were put in coolers and transported by cars and – no, not planes or trains – but helicopters to a pair of sites in Southern California…

(SOUNDBITE OF FROGS CROAKING)

ROTT: …That had been cleared of invasive bullfrogs which would otherwise eat them. Which brings us to now, many translocations and years later and the acoustic challenge of figuring out if their efforts worked – if the frogs are breeding. Bennett Hardy is a biologist with the San Diego Natural History Museum.

BENNETT HARDY: We want to listen for their calls.

(SOUNDBITE OF FROGS CROAKING)

HARDY: So when frogs are calling, most of the time, that’s the male of the species.

ROTT: Either telling other males to bug off or saying to females the frog equivalent of ‘sup. Those ribbits you’re hearing, by the way, are tree frogs, not the reintroduced frogs we’re listening for.

HARDY: I’d love to be out there every night at these ponds and – with my tent and camping and being up every night and trying to listen for them, but it’s just not feasible.

ROTT: So the researchers put microphones around the ponds, collecting thousands of hours of audio files like the ones we’re listening to.

HARDY: Now we need thousands of hours of ears to be able to sort through all of that data, which is a huge task. And that’s where advancements in technology through AI have become really helpful for us.

ROTT: The team trained an AI model to go through the sound files and find any California red-legged frog calls. It also identified bullfrog calls, letting scientists know if the predators were coming back into the area. And this winter, for the first time in decades, the California red-legged frog was heard again in Southern California.

(SOUNDBITE OF FROGS CROAKING)

ROTT: They’re that grunting sound you hear beneath the tree frogs, kind of like a finger rubbing on a balloon.

(SOUNDBITE OF FROGS CROAKING)

ROTT: Soon after, near the microphone that picked up that sound, a new egg mass was found.

HARDY: So we knew right then and there that, hey, all of our hard work over the last six years and beyond is starting to pay off.

ROTT: With time, Hardy says, the hope is that the frogs will start to naturally disperse to other areas on their own. And with funding, they’ll do more relocations to give them another hopping hand.

Nate Rott, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Iran’s president defies U.S. demands while apologizing for strikes on neighbors

President Masoud Pezeshkian said Saturday that a demand by the U.S. for an unconditional surrender is a "dream that they should take to their grave." He also apologized for Iran's attacks on regional countries.

What the Trump administration says about why it went to war with Iran

The Trump administration says it is "laser focused" and mission driven, but the messaging has been varied. The range of cited motivations for striking Iran now are sometimes at odds with each other.

Trump looks to turn attention to Western Hemisphere at Americas summit

President Trump is set to gather with Latin American leaders on Saturday at his Miami-area golf club as his administration looks to turn attention to the Western Hemisphere, at least for a moment.

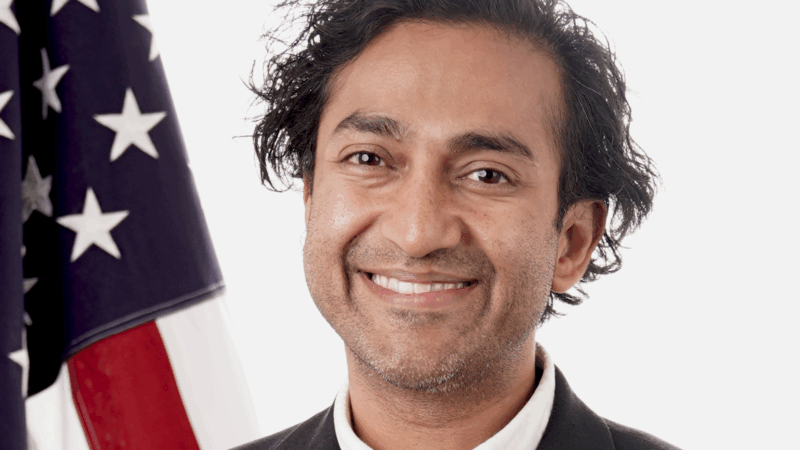

Trump administration’s embattled FDA vaccine chief is leaving for the second time

The FDA's controversial vaccine chief, Dr. Vinay Prasad, is leaving the agency. It's the second time he has abruptly departed following decisions involving the review of vaccinations and specialty drugs.

Family, former presidents and a Hall of Famer give Rev. Jesse Jackson a final sendoff

Several speakers at Jackson's funeral invoked his hallmark catchphrases: "Keep hope alive" and "I am somebody."

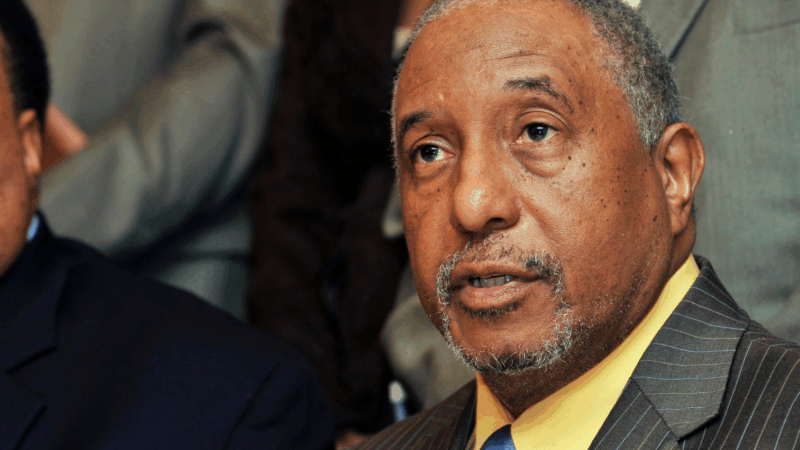

Bernard LaFayette, Selma voting rights organizer, dies at 85

Bernard LaFayette, who died Thursday, laid the foundations of the Selma, Alabama, campaign that culminated in the passage of the Voting Rights Act. He was a Freedom Rider and helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.