Many farmers are going into 2026 on the brink

EDITOR’S NOTE: This year, NPR’s American Voices series has told the stories of people directly affected by President Trump’s policies since his return to the White House. Trump has said farmers would feel short term pain as he shakes up American trade. The White House now says 2026 will be a lot better for them. But optimism was hard to find on a recent road trip across South Dakota.

MITCHELL, S.D. – 2025 brought another unprofitable harvest in the Heartland, where soybean farmers were already dealing with high equipment and fertilizer costs due to inflation and tariffs.

Kevin Deinert farms the same land his great-great-grandfather did near Mitchell, South Dakota, about 80 miles from the Iowa state line.

“I’d be probably the fifth generation, I’ve got sons, that’d be the sixth that possibly would want to take over the farm,” Deinert says over the hum of his tractor.

Lately it’s a fight to just stay in business one year to the next, never mind legacies. Deinert is 38, in a thick, worn hoodie, his brown hair cut short. He climbs out of his tractor and onto the slush in front of four-story high grain bins.

They’re still full of soybeans.

“Too full,” he says.

Deinert is hoping to store them a few more months, hang on until maybe prices go up and there’s a new trade deal with China, historically the Dakotas’ biggest buyer.

“We haven’t seen anything in writing, and until we do it’s hard to get overly excited, we’re optimistic,” he says.

The White House says China agreed to buy 12 million bushels of soybeans this year and about double that next year. That would be roughly what they bought from here before Trump’s trade war, in which China stopped buying any U.S. soybeans in retaliation for tariffs of up to 145 percent he imposed on their exports to America. In farm country, there are growing questions about whether this was all this even worth it.

Deinert isn’t eager to get into the heated politics.

“I understand why they did it and how they did it,” he says. “It’s unfortunate that usually the American farmer and specifically the soybean farmer is used on the tip of the spear.”

Heartland states went big for Trump in 2024. He racked up bigger gains in rural counties than in his two previous runs. The president’s recent $12 billion aid package to farmers reeling from his trade war is billed as a “bridge payment,” to buy more time for negotiations.

Running out of time and patience

Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins has insisted farmers will get the certainty they’ve been asking for in the coming weeks so they can go to their banker and get loans. In Aberdeen, South Dakota, about 130 miles north of Deinert’s farm, John Kippley is skeptical of federal promises, and says farmers needed the money yesterday.

“You can’t take that to the bank and tell ’em that, you’re gonna get this bridge payment and they’ll ask you how much, [well] nobody knows,” he says.

Kippley runs a tax firm here. Many of his clients went to harvest in the red this year and bankers are now telling some to sell out. The government lending firm Farmer Mac predicts more than half of farmers won’t turn a profit next year.

“If they don’t have a dad or a grandpa or an uncle that’s got everything paid for to work with, you’re most likely not going to be able to stay farming,” Kippley says

Kippley is eighty. His farm just barely made it through the crash of the 1980s, which caused huge rural flight. People are worried 2026 could bring another bust, maybe worse, with ripple effects like more small town hospitals and schools closing.

Farmers are still wondering what the end game is

The anxiety was palpable at the 115th meeting of the South Dakota Farmers Union in Huron.

Farmers unions historically have leaned Democrat. But even more conservative groups like the Farm Bureau have been more muted than usual in their praise for Trump on the $12 billion aid package, calling it “a good first step.”

In an interview between sessions, South Dakota Farmers Union president Doug Sombke isn’t sure what the end game is.

“I mean he’s back at the fire trying to put it out with a garden hose,” Sombke says. “And it’s an inferno.”

Sombke says the tariffs are just compounding problems that have been building since that farm economy crash in the 1980s. Later, in the ’90s, those who stayed in business were told to get big and export to become profitable and survive. Sombke says it’s hard to get back to just growing for America like Trump has said he wants.

“This time it’s even going to be worse for the simple fact that farmers today have so much leveraged,” Sombke says. “I mean, the borrowing amount that they have, it’s not just tens of thousands anymore, it’s hundreds of thousands and somewhere in the millions.”

It’s not all doom and gloom in the Ag sector though

(Kirk Siegler | NPR)

An early season blizzard is whipping a brutal wind across the prairie, which can feel bleak especially this time of year when daylight is so precious. Country highways weave through farms, the occasional abandoned homestead stands eerily in the frozen stubble of corn fields.

Finally, 150 miles later, the massive Missouri River and the unofficial line where the row crops of the lush Midwest start to give way to the rangeland of the arid West.

This is cattle country.

“The old rule always was always the 100th Meridian, the 100th to the 101st Meridian,” says Kory Bierle, with a warm handshake as he jumps out of his pickup.

Bierle’s family has ranched here along the rugged, shale-carved banks of the Bad River for more than a century.

There are a lot of headwinds in the ag economy right now. But Bierle, 60, still has hope going into 2026. He recounts fondly a story he heard from another rancher who visited the White House for a ceremony. A staffer asked them to hang back because the President wanted to meet them after.

“And Trump brought the cowboys back in and said, ‘these guys, these guys are what make America great,'” Bierle says.

Bierle’s also optimistic because high beef prices are one of the few bright spots in the farm economy right now. Ranchers are getting a reprieve after years of drought and the pandemic.

“We’re not partying yet but you know, you feel for them [the farmers], because at the same time we know exactly what it’s like,” he says.

He’s finally got enough money coming in to pay off some debts. But he’ll keep budgeting conservatively. He won’t expand his cattle herd anytime soon. It feels like there’s always another shock no one sees coming, that Black Swan event, just around the next bend.

Transcript:

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

NPR’s American Voices series tells the stories of people affected by President Trump’s policy since his return to the White House. That includes farmers. Trump himself said they would feel short-term pain as he shakes up American trade policies. The White House now says 2026 will be better for them. NPR’s Kirk Siegler took a road trip across South Dakota farm country to check in.

KIRK SIEGLER, BYLINE: 2025 was another unprofitable harvest in the heartland, where soybean farmers were already dealing with high equipment and fertilizer costs due to inflation and tariffs.

KEVIN DEINERT: Parking brake on.

SIEGLER: Kevin Deinert farms the same land his great-great-grandfather did near Mitchell, South Dakota, about 80 miles from the Iowa state line.

DEINERT: Yeah. You know, a lot of generations. I consider I’d be probably the fifth generation. I got sons. That’d be the sixth that possibly will want to take over the farm.

SIEGLER: Lately, it’s just a fight to stay in business one year to the next. Never mind legacies. Deinert is 38 in a thick, worn hoodie, his brown hair cut short. He climbs out of his tractor and onto the slush in front of two four-story-high grain bins.

DEINERT: Get rid of some of the ice.

SIEGLER: They’re still full of soybeans. Deinert is hoping to store them a few more month. Hang on until maybe prices go up and there’s a new trade deal with China, historically, the Dakotas’ biggest buyer.

DEINERT: We haven’t seen anything in writing. And until we do, it’s hard to get overly excited. We’re optimistic.

SIEGLER: The White House says China agreed to buy 12 million bushels of soybeans this year and about double that next year, which would be roughly what they bought from here before Trump’s trade war. So what’s this all even worth it? Deinert isn’t eager to answer that.

DEINERT: No, I understand why they did it and how they did it. It’s unfortunate that usually the American farmer, and specifically the soybean farmer, is used on the tip of the spear.

SIEGLER: Farmers as negotiating chips. The heartland states went big for Trump. In 2024, he racked up bigger gains in rural counties than in his two previous runs. Trump’s recent $12 billion aid package to farmers reeling from his trade war is billed as a bridge payment to buy more time for negotiations.

(SOUNDBITE OF ENGINE RUNNING)

SIEGLER: This agriculture secretary, Brooke Rollins, insists farmers will get the certainty they’ve been asking for in the coming weeks so they can go to their banker and get loans. John Kippley says farmers needed the money yesterday.

JOHN KIPPLEY: You can’t take that to the bank and tell them that you’re going to get this bridge payment. And they’ll ask you how much? Nobody knows.

SIEGLER: Kippley runs a tax firm in the town of Aberdeen. Many of his clients went to harvest in the red this year, and bankers are now telling some to sell out. The government lending firm Farmer Mac predicts more than half of farmers won’t turn a profit next year.

KIPPLEY: If they don’t have a dad or a grandpa or an uncle that’s got everything paid for to work with you, you’re most likely not going to be able to stay farming.

SIEGLER: Kippley is 80. His farm just barely made it through the crash of the 1980s, which caused huge rural flight. People are worried 2026 could bring another bust, maybe worse, with ripple effects like more small-town hospitals and schools closing.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Good afternoon, everybody. Welcome to the 110th annual South Dakota Farmers Union Convention.

SIEGLER: This anxiety was palpable at the Crossroads Hotel in Huron. The next speaker at the podium was Governor Larry Rhoden, who took over when Kristi Noem became Homeland Security secretary. He tried to reassure the crowd, saying Trump’s Cabinet, especially Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, gets farmers and what they’re going through.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

LARRY RHODEN: Brooke understands the implications of some of the unfortunate things that can come out of their boss’s mouth.

SIEGLER: That got some chuckles and head nods. Farmers’ unions historically have leaned Democrat. But even more conservative groups like the Farm Bureau have called the $12 billion aid package a good first step, with praise for Trump more muted than usual. South Dakota Farmers Union president Doug Sombke isn’t sure what the endgame is.

DOUG SOMBKE: I mean, he’s back at the fire trying to put it out with a garden hose. And it’s an inferno.

SIEGLER: Sombke says the tariffs are just compounding problems that have been building since the farm economy crash in the ’80s. Those who stayed in business were told to get big and export to survive. So it’s hard to get back to just growing for America like Trump said he wants.

SOMBKE: And I think this time it’s even going to be worse for the simple fact that farmers today have so much leverage. I mean, the borrowing amount that they have to – I mean, it’s not just tens of thousands anymore. There’s just hundreds of thousands and somewhere in the millions.

(SOUNDBITE OF WIND HOWLING)

SIEGLER: An early-season blizzard is whipping a brutal wind across the prairie, which can feel bleak, especially this time of year when daylight is so precious. Country highways weave through farms. The occasional abandoned homestead stands eerily in the frozen stubble of cornfields. Finally, 150 miles later, the massive Missouri River and the unofficial line where the row crops of the lush Midwest start to give way to the rangeland of the arid West.

KORY BIERLE: The old rule was always the 100th meridian, the 100th through the 101st meridian.

SIEGLER: Yeah.

BIERLE: And you…

SIEGLER: So I just crossed it?

BIERLE: You did. Yep.

(LAUGHTER)

SIEGLER: This is cattle country near the town of Midland. Kory Bierle’s family has ranched here along the rugged, shale-carved banks of the Bad River for more than a century.

BIERLE: It’s a bad river because – Wakpa-Sica is what the Lakota and the natives called it. It floods so easily.

SIEGLER: There are a lot of headwinds in the ag economy right now, but Bierle, who’s 60, still has hope going into 2026. He recounts fondly a story he heard from another rancher who visited the White House for a ceremony. A staffer asked them to hang back because the president wanted to meet them after.

BIERLE: And Trump brought them – brought the cowboys back in, ranchers back in and said, these guys are what make America great.

SIEGLER: Bierle is also optimistic because high beef prices are one of the few bright spots in the farm economy right now. Ranchers are getting a reprieve after years of drought and the pandemic.

BIERLE: Yeah. We’re not partying yet, but, you know, you feel for them because, at the same time, we know exactly what it’s like.

SIEGLER: He’s finally got enough money coming in to pay off some debts, but he’ll keep budgeting conservatively.

BIERLE: Especially equipment costs. You know, there’s a reason I’m driving a 2012 old pickup. They’re just – they’re so dang expensive.

SIEGLER: He won’t expand his cattle herd anytime soon, though. He says it feels like there’s always another shock no one sees coming, that black swan event just around the next bend.

Kirk Siegler, NPR News, Midland, South Dakota.

(SOUNDBITE OF RENA JONES’ “OPEN ME SLOWLY”)

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.

Baz Luhrmann will make you fall in love with Elvis Presley

The new movie is made up of footage originally shot in the early 1970s, which Luhrmann found in storage in a Kansas salt mine.

Forget the State of the Union. What’s the state of your quiz score?

What's the state of your union, quiz-wise? Find out!

As the U.S. celebrates its 250th birthday, many Latinos question whether they belong

Many U.S.-born Latinos feel afraid and anxious amid the political rhetoric. Still, others wouldn't miss celebrating their country

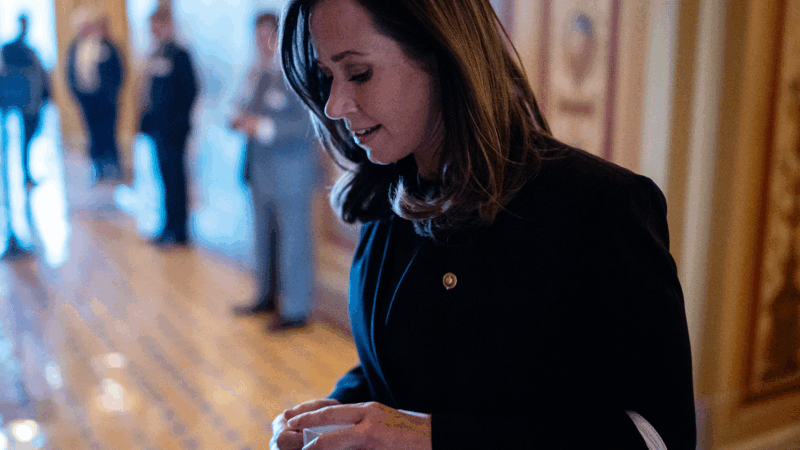

SNL mocked her as a ‘scary mom.’ In the Senate, Katie Britt is an emerging dealmaker

Sen. Katie Britt, Republican of Alabama, is a budding bipartisan dealmaker. Her latest assignment: helping negotiate changes to immigration enforcement tactics.

A team of midlife cheerleaders in Ukraine refuses to let war defeat them

Ukrainian women in their 50s and 60s say they've embraced cheerleading as a way to cope with the extreme stress and anxiety of four years of Russia's full-scale invasion.