Kilmar Abrego Garcia becomes symbol of mistaken deportations

The case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia captured national headlines last year as part of a wave of criticism against the second Trump administration’s aggressive immigration enforcement.

It was the speed of his deportation — from working in Maryland one week, to getting whisked off to a notorious prison in El Salvador the next. But it was also because it was a mistake: something a government lawyer admitted in court.

Immigration lawyers said Abrego Garcia’s landmark case highlights the challenges with the speed and scale of the Trump administration’s goal of mass deportations.

“We really thought this was going to be one of a kind,” said Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, one of Abrego Garcia’s lawyers. “If anything, it was just the tip of the spear. There have been countless illegal deportation cases since then. If anything, the problem is getting worse and not better.”

Sandoval-Moshenberg said he alone has a dozen other plaintiffs like Abrego Garcia. It’s impossible to quantify how many such mistaken deportations are happening — as only a small subset of immigrants have lawyers to argue for their return. But judges have stepped in with other cases.

For example, last April — the same month a Maryland judge told the government to bring Abrego Garcia back to the U.S. — another judge in the state asked for the return of Daniel Lozano-Camargo, a 20-year-old Venezuelan man, identified in court documents as “Cristian.”

And in July, a New York appeals panel ordered immigration officials to return Jordin Melgar-Salmeron, a 31-year-old Salvadoran.

All three were held at a notorious prison in El Salvador that has since been described by detainees as unsanitary and violent. Judges said that these removals violated court orders.

Meeting deportation targets

Advocates warn that the speed at which the administration is removing some people increases the possibility of errors. President Trump has set a target of one million deportations a year, and administration officials have often set daily quotas for removals.

In some cases, people have been in custody for just days before they’re deported — either to their home countries or to third countries that agree to take in deportees from the U.S.

“They are errors that result when different parts of the system aren’t communicating well or when things are moving too fast. And things moving too fast is really where we’ve seen this administration lean in,” said Dara Lind, a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council.

Some people get sent to countries where judges have specifically prohibited it. That’s what happened with Abrego Garcia’s deportation to El Salvador, even after an administrative judge agreed he had a credible fear of being tortured there.

Other people are deported while they’re still pursuing legal processes to stay in the U.S., such as asylum cases.

“The question is really, is the government making sure that an individual person is removable and doing the things it’s legally obligated to do to remove them? Not, ‘Does somebody have legal status or not?'” Lind said.

For its part, the Department of Homeland Security declined to comment on Abrego Garcia’s specific case this week, but has argued that judges erred in their decisions, and that anyone who’s in the U.S. illegally should be deported. It’s also said it complies with all court orders.

Deportation errors not new, but appear more frequent

The administration’s spotlight on immigration has resulted in more cases coming across the radar of attorneys, said Lind. But she said it is difficult to say whether these kinds of incidents are happening more frequently than they have under prior administrations.

For example, a 2021 Government Accountability Office report found that over a five year period, U.S. citizens had encounters with immigration officers that could lead to their arrest and even deportation.

“Wrongful deportations have taken place under all different administrations, so this is not novel,” echoed Trina Realmuto, executive director of the National Immigration Litigation Alliance, which is a nonprofit that provides legal assistance to organizations and immigrants. But she said she has noticed an uptick in these cases coming to her organization over the past year.

Sandoval-Moshenberg, one of Abrego Garcia’s lawyers, said he currently has about a dozen similar cases of wrongful deportations — with more people likely turning to him after he gained a reputation for defending such cases.

“It’s been lots of people who were deported precisely to the country that they were not allowed to be deported to,” Sandoval-Moshenberg said. “And it’s amazing to me because usually it used to be that when the government gets in trouble for doing something, they would at least tighten up and make an effort not to do it again. And that just doesn’t seem to be the case here.”

The Trump administration has, without evidence, accused Abrego Garcia of being a member of the Salvadoran-affiliated gang MS-13 and a terrorist and dubbed him a “wife beater” and “child predator.” They also charged him with human smuggling after bringing him back to the country — something he’s denied.

Generally, the Trump administration in public statements has defended its deportations, often arguing that anyone without legal status is subject to removal – even if government lawyers admit the mistake in court.

Another case involved a plaintiff who goes by O.C.G., a Guatemalan man wrongfully deported to Mexico despite a legal order prohibiting his deportation there. Mexico turned around and sent O.C.G. to Guatemala, even though a judge had issued an order of protection blocking him from deportation to his homeland. His lawyers say he then went into hiding.

The administration eventually brought him back to the U.S. and he was granted bond to stay out of detention while his case is adjudicated.

“America’s asylum system was never intended to be used as a de facto amnesty program or a catch-all, get-out-of-deportation-free card,” said Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary for public affairs at the Department of Homeland Security.

“Yet, this federal activist judge ordered us to bring him back, so he can have an opportunity to prove why he should be granted asylum to a country that he has had no past connection to.”

Immigration lawyers said that O.C.G’s case exemplifies one of the reasons why mistakes can happen more frequently: the expanded use of “third country” removals.

“Those countries are then turning around and deporting people to countries where a U.S. immigration judge has said they will be persecuted or tortured,” Realmuto with the National Immigration Litigation Alliance said.

Caught in the grind of immigration bureaucracy

Immigration enforcement is generally decentralized.

People are shuffled around various detention centers in the U.S. They might have cases within the Justice Department’s immigration court system, or in federal courts.

Various legal protections from deportation, including deferred action and humanitarian parole programs, are administered by different agencies than those that are detaining people.

That means immigrants who should have protection from deportation are sometimes caught in the crosshairs.

For example, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals or DACA program grants people who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children protection from deportation.

But in March, officials deported Evenezer Cortez Martinez, a DACA recipient in Missouri, to Mexico. He was allowed to return after two weeks.

The advocacy coalition Home is Here has tracked at least 22 instances of people with valid DACA status getting swept up in arrests, placed in detention or deported. In 2025, it also found additional instances of people waiting for their DACA renewal who were deported.

Speed of deportations

The speed of immigration enforcement compounds the problems. Lawyers have cited numerous instances of court orders or protections from removal being issued minutes before someone is supposed to be on a flight, or already in the air.

Federico Reyes Vasquez was deported to Mexico four days after he was first detained in December, and after a federal district judge in Utah issued a stay in his removal.

“It is nearly impossible to get information from the Department of Homeland Security when an individual is detained. We didn’t know where he was. His status on the detainee locator showed that he wasn’t in their custody when we knew that he, in fact, was,” said Alec Bracken, the immigration attorney representing Reyes Vasquez.

He said he was trying to release Reyes Vasquez from detention when he suddenly learned his client was in Mexico.

Utah District Court Judge Jill Parrish ordered the administration to facilitate Reyes Vasquez’s return. According to court records, the administration admitted that the removal was in violation of the court order and that information on the stay had not been correctly communicated to the people deporting him.

“At a hearing on this issue held on December 31, counsel for Respondents acknowledged the removal was in violation of the court’s Order and asserted Respondents are working with petitioner’s counsel to facilitate petitioner’s return to the United States,” according to Parrish’s order. It notes the government said ICE was made aware of the order not to remove Reyes Vasquez — but the agency’s Enforcement and Removal Operations division wasn’t aware of it before they transferred and deported him.

Still, McLaughlin, the DHS spokesperson, said “there was no mistake,” in response to NPR’s questions about the case.

“This [temporary restraining order] was not served to ICE until after the criminal illegal alien was removed,” she said, noting that Reyes Vasquez has a conviction for driving under the influence.

“Under President Trump and Secretary Noem, if you break the law, you will face the consequences. Criminal illegal aliens are not welcome in the U.S.”

Bracken argued that he never got information from the Homeland Security Department about why they wanted to deport his client in the first place. When he was deported, lawyers on both sides were in the early stages of litigating whether he should even be detained.

“The U.S. government has 90 days to execute [a removal] order. They didn’t have to do it so quickly,” Bracken said. “Instead, they wanted to circumvent the law and do it faster.”

DHS has a new deadline of Feb. 5 to bring Reyes Vasquez back to the U.S.

Where are they now?

Lawyers for Reyes Vasquez remain in contact with him while he’s in Mexico.

Other people whom judges have said were wrongly deported face a more uncertain fate.

Lozano Camargo, the Venezuelan man sent to El Salvador, was later returned to Venezuela as a part of a broader prisoner exchange.

According to court documents, DOJ lawyers said that should he be returned to the U.S. — he would be placed in indefinite detention while his asylum case played out. Lawyers representing Lozano Camargo said their client was apprehensive to return to the U.S. given his four-months-long incarceration in the El Salvador prison; he was afraid of being detained again or sent to another third country.

Court records show attorneys lost touch with their client in August “and are concerned about his safety and well-being.”

“The President and Secretary Noem will not allow a foreign terrorist organization to operate on American soil,” McLaughlin said in response to NPR’s questions about this case.

Melgar-Salmeron, a native of El Salvador, remains in the notorious prison there. Despite a court ordering that communication between Melgar-Salmeron and his lawyers be facilitated by El Salvador, court records show his attorneys have struggled to get back in contact with him.

Melgar-Salmeron was removed due to a “confluence of errors” minutes after a judge ordered the government to keep him in the U.S., according to court records. McLaughlin said he had a final order for removal in 2023.

As for Abrego Garcia, he’s out of detention for now. The judge in his case is still weighing whether to allow immigration officers to detain him again while his criminal and immigration cases play out.

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

Kilmar Abrego Garcia was living and working in Maryland when the Trump administration detained him and deported him to El Salvador last spring. They later admitted the deportation was a mistake. A judge ordered him returned to the U.S., which did happen eventually, and the case has become a symbol for the problems of immigration enforcement over the past year. Immigration attorneys and advocates say Abrego Garcia’s case is not the only time that someone was mistakenly deported. NPR’s Ximena Bustillo is here to explain. Hi, Ximena.

XIMENA BUSTILLO, BYLINE: Hey, Scott.

DETROW: Remind us what happened here.

BUSTILLO: So an immigration judge had previously provided a protection from deportation specifically to El Salvador, and Abrego Garcia quickly became a symbol for the Trump administration’s clashes with the courts and the pitfalls of a quickly implemented mass deportation agenda. Here’s one of his lawyers, Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg.

SIMON SANDOVAL-MOSHENBERG: The government, since Day 1, has really tried to use this case to make the point that they can do whatever they want, whenever they want to whomever they want, and specifically the federal courts don’t have the power to stop them.

BUSTILLO: The Trump administration did return him to the U.S. and immediately charged him with human smuggling. Abrego Garcia is now out of detention and awaiting trial in Maryland, and he denies those allegations.

DETROW: I mentioned this is not the only time something like this has happened. You’ve covered similar cases.

BUSTILLO: Right. The administration has admitted to deporting others in error. Two other men were wrongfully deported to El Salvador and neither has returned, according to court documents. Another man, also known in court documents as OCG, had a similar protection from deportation, specifically to Guatemala. He was deported to Mexico and then sent to Guatemala after that anyways. His lawyers tell me that he was in hiding there until immigration officials from the U.S. facilitated his return back here. I spoke with Dara Lind of the American Immigration Council, and she said wrongful deportations happen across administrations regardless of political parties.

DARA LIND: There are errors that happen when different parts of the system aren’t communicating well or when things are moving too fast. And things moving too fast is really where we’ve seen this administration lean in.

DETROW: Walk me through the legal definition here of a wrongful deportation.

BUSTILLO: Right. Lawyers tend to break down about three types of wrongful deportations. First, we have people with some form of protection from deportation. An example of this could be a person with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. That’s a program for some people brought to the U.S. illegally as children. Second is people who are deportable but are sent to countries that immigration judges had agreed they would face danger or torture, and they’re sent there against those legal orders anyways, so like Abrego Garcia.

DETROW: And then, sometimes people have due process claims – right? – but then they’re deported before they can argue the cases?

BUSTILLO: Right. That’s the third way. And sometimes it’s happened even after federal judges have made it clear that they should not be deported yet.

DETROW: So this has happened over time. What stands out to you about what is different with the mistakes that are happening under the Trump administration?

BUSTILLO: So this administration, lawyers told me, is shining a bigger spotlight on immigration and trying to act as quickly as possible. So both those things make mistakes more likely and also more noticeable. Now, in some instances, the Trump administration has facilitated the return of people removed, but not always. Lawyers have lost touch with their clients, deadlines are pushed for weeks and accountability seems limited. Here’s Lind again.

LIND: However, what we’ve seen in the cases that have come up – like, Kilmar Abrego Garcia is a great example of this – right? – like, the government could respond to the revelation of the error by saying, oh, wow, this is our screw-up. We violated the law. We’re going to take responsibility to get that person back in the U.S. or to get that person out of the country where they shouldn’t have been deported to. And they have not taken that attitude.

DETROW: What does this all say about the broader immigration system?

BUSTILLO: It tells us that it’s a really confusing system. DHS told me in response to these cases that, you know, it’s still going to deport people who should be deported, and they dispute the facts in judges’ decisions. At the same time, there are many different people who can decide an immigrant’s fate at different levels and parts of government, and these parts are not always talking to each other. So the space for mistakes just gets bigger.

DETROW: NPR’s Ximena Bustillo, thanks so much.

BUSTILLO: Thank you.

How Rupert Murdoch created a media empire — and ‘broke’ his own family

Journalist Gabriel Sherman has covered the Murdoch family for nearly two decades. In his new book, Bonfire of the Murdochs, he chronicles the protracted public battle for control the family business.

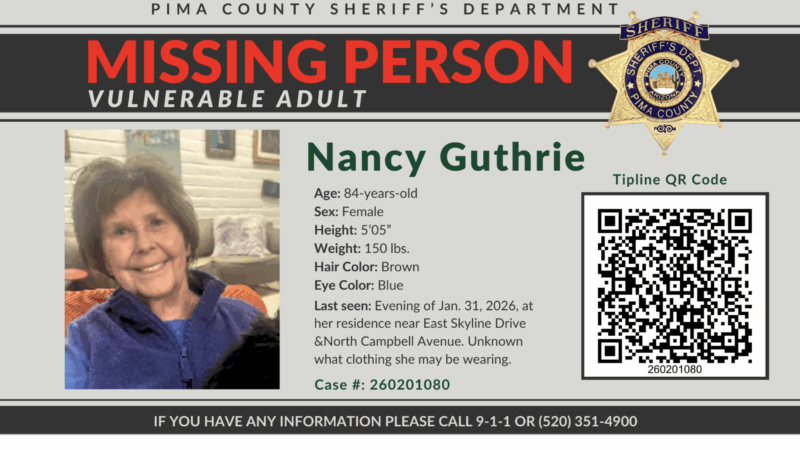

What we know about Savannah Guthrie’s missing mother

Nancy Guthrie is 84 and has mobility issues, but she is mentally sharp, Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos said. She was last seen Saturday evening.

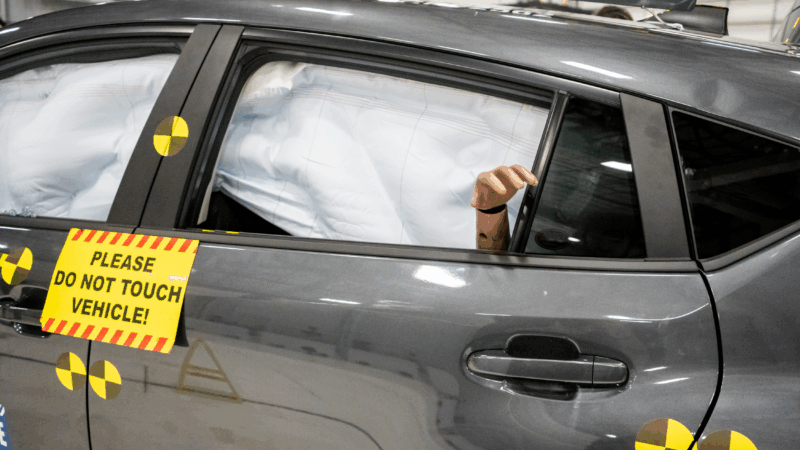

Back seats aren’t as safe as they should be. A crash test is trying to help

Better engineering has made the front seat much safer in head-on collisions. But the back seat hasn't kept pace. It's a problem one vehicle safety group is trying to solve.

A new generation revives ‘The Muppet Show’ and it’s as delightful as ever

This isn't the first reincarnation of Jim Henson's crew, but it's one of the best in a very long time. Seth Rogen is an executive producer, and Maya Rudolph and Sabrina Carpenter guest star.

House votes to end partial government shutdown, setting up contentious talks on ICE

The House has approved a spending bill to end a short-lived partial government shutdown. Now lawmakers will begin contentious negotiations over new guardrails for immigration enforcement.

Despite a ‘ruptured’ knee ligament, Lindsey Vonn says she will compete in the Olympics

The 41-year-old's remarkable comeback from retirement was thrown into jeopardy after she hurt her knee during a crash in competition last week. But that won't keep her from racing in the Olympics.