Is Edinburgh’s Fringe still fringe, or has it — gasp — gone mainstream?

EDINBURGH, Scotland — For decades, devotees repeated rumors in hushed reverence about starving artists sleeping in bathtubs, out of dedication to the Fringe — one of the world’s biggest theater and comedy festivals.

Now they deride corporate sponsors and local residents for cashing in and renting out those mythical bathtubs.

Fringe dates back to 1947, when eight theater groups turned up at the Edinburgh International Festival uninvited. They staged their shows on the fringe – the edgy margins – of that more rarefied festival. Their vibe was alternative, weird, experimental — anything goes.

It’s since become where eccentric theater kids find kindred spirits — and sometimes, fame.

Robin Williams performed in the early 1970s. In 2005, before writing Hamilton, Lin-Manuel Miranda busked at Fringe, calling it “the best summer of our lives.” It’s where the Netflix stalker hit Baby Reindeer originated, where Phoebe Waller-Bridge developed Fleabag, and where the 90s percussion group STOMP won an early following.

Fringe has long since eclipsed the original festival it was founded alongside. It typically sells upwards of 2.5 million tickets a year. But 80 years on, performers and spectators alike say rising costs threaten the Fringe’s free-for-all vibe.

“It’s put me off coming next year,” says Liz Holland, a repeat visitor from Yorkshire, England, who only managed to come this year because she locked in an off-the-books Airbnb rental three years ago. It’s a 45-minute walk from Fringe venues. “I used to see so many shows back-to-back. But tickets cost two or three pounds ($2.70 to $4) [per show] more than they used to. So I’m having to be more selective about what I go and see.”

Tickets are still a steal compared to Broadway or the West End; most cost £10 or £15 British pounds ($13.50 to $20), but some cost more.

Unlike some other festivals that invite big name performers and might pay for their travel, the open-to-all nature of Fringe means artists themselves have to foot the bill.

For comedians and actors, “it costs so much to do the festival now, it’s a high-risk undertaking as a performer,” says Marjolein Robertson, a Scottish storyteller and comedian who’s been coming to Fringe since 2011 and performing since 2016. “A lot of people will leave thousands of pounds poorer.”

Robertson lives in London and says she can only afford to perform at Fringe because she’s able to crash — for a month — on an Edinburgh friend’s couch.

One of the world’s biggest events, but artists pay their own way

Every August, Edinburgh’s streets fill with acrobats, mimes, and people in all sorts of costumes. On a single day this month, NPR spotted two men in bridal gowns, a giraffe and a whole family dressed as bananas.

This year’s festival ran Aug. 1-25. The last night of performances is Monday.

Fringe coincides with the Edinburgh Book Festival and several other events. Police say the Scottish capital’s population nearly doubles. Fringe organizers say their event alone is exceeded in size only by the Olympics or soccer’s World Cup.

All those people drive up demand. Taxis and hotels jack their prices. Crowds are getting older, more affluent.

“I think it’s just about how badly you want to come!” says Zainab Johnson, a writer, actor and comedian who was raised in New York City and now lives in Los Angeles.

She’s had her own Amazon Prime Video standup special, called Hijabs Off, and played a recurring role on the sci-fi comedy show Upload. But this is her first Fringe.

“It’s made me feel like I was back in my open mic days, you know?” Johnson says. “Other big festivals around the world that I’ve done, they’ve flown me out, they’ve put us up in like really nice accommodations, even provide a meal per diem. This was drastically different. This, you’re footing the cost of everything.”

She says she wanted to see what all the hype is about. She also wants to be what she calls an “ambassador” for America, at a time when people abroad are really curious about U.S. politics.

“You know what America’s like? It’s like that family member, they drunk, and they knockin’ s*** over,” Johnson jokes. “But you like, ‘No, my uncle, he’s a good uncle.'”

The opening line of her comedy show Toxically Optimistic is: “I’ve got a gun.” Throughout the one-hour show, Johnson explains why she feels like she needs it, as a Black Muslim woman in America — and how she’s not giving up on her country.

Performers say it’s still worth it

Robertson, the Scottish comedian, grew up on the far-north Shetland Islands, a 12-hour boat ride from any comedy club. But her father, who first attended Fringe in 1959, raised her on Fringe lore. She recounts one particular show her father told her he saw in the 1970s or 80s.

“The show was meant to start and nothing happened, and then this man started eating cream crackers incredibly messily and noisily in the front row. The man was like, ‘Well, if no one else is going to do anything, I’ll get up,’ and this man got up on stage! And dad said he’d never seen anything like it. He felt so awkward and cringe and embarrassment for this man,” Robertson recalls. “And then all of a sudden he realized, this is the bit! This is the joke.”

It was performance art. And the man chomping cream crackers was Rowan Atkinson, later known as Mr. Bean.

With stories like that, Robertson was hooked. She briefly worked as a town planner on her native island — where there’s only one town — before ditching that and devoting herself to comedy. Her Fringe show this year, Lein, mixes Shetland folklore with jokes. It’s part three of a trilogy, performed in consecutive years.

“There’s nothing better for you as a performer to do a show every day for a month, because it grows and changes, and you get better, and you develop your craft,” Robertson says.

But she says she worries Fringe — which was always inclusive, open to all — is becoming out of reach for artists who are aren’t already famous, or rich.

“The Fringe is now, in many ways, the beast!” Robertson says. “What’s that classic phrase? You either die the hero, or live long enough to become the villain.”

Maybe, she says, artists just need to create a new fringe of the Fringe.

NPR producer Fatima Al-Kassab contributed to this story. Jennifer Vanasco edited for broadcast and digital.

Trump calls SCOTUS tariffs decision ‘deeply disappointing’ and lays out path forward

President Trump claimed the justices opposing his position were acting because of partisanship, though three of those ruling against his tariffs were appointed by Republican presidents.

The U.S. men’s hockey team to face Slovakia for a spot in an Olympic gold medal match

After an overtime nailbiter in the quarterfinals, the Americans return to the ice Friday in Milan to face the upstart Slovakia for a chance to play Canada in Sunday's Olympic gold medal game.

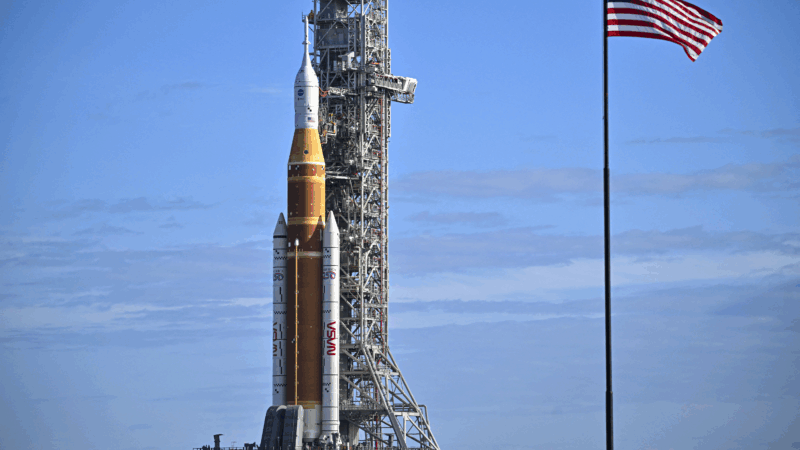

NASA eyes March 6 to launch 4 astronauts to the moon on Artemis II mission

The four astronauts heading to the moon for the lunar fly-by are the first humans to venture there since 1972. The ten-day mission will travel more than 600,000 miles.

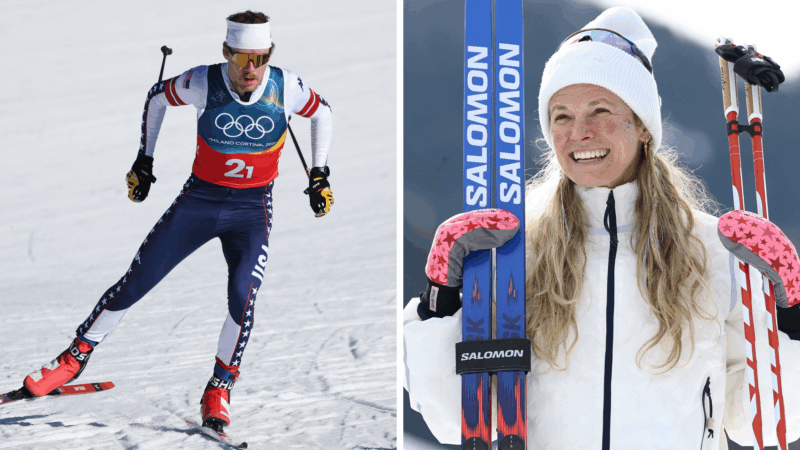

Skis? Check. Poles? Check. Knitting needles? Naturally

A number of Olympic athletes have turned to knitting during the heat of the Games, including Ben Ogden, who this week became the most decorated American male Olympic cross-country skier.

Police search former Prince Andrew’s home a day after his arrest over Epstein ties

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor, the British former prince, is being investigated on suspicion of misconduct in public office related to his friendship with the late convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Violinist Pekka Kuusisto is not afraid to ruffle a few feathers

On his new album, the violinist completely rethinks The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams, and leans into old folk songs with the help of Sam Amidon.