How safe is the food supply after federal cutbacks? Experts are worried

Paula Soldner inspected meat and poultry plants around southern Wisconsin for 38 years: “I’m talking brats, hot dogs, summer sausage, pizza.”

Her Department of Agriculture job required daily check-ups on factories to ensure slicers were cleaned on schedule, for example. Her signoff allowed plants to put red-white-and-blue “USDA inspected” stickers on grocery-store packages.

Last month, Soldner took the Trump administration up on its offer of early retirement, joining an exodus from the Food Safety and Inspection Service that began under President Biden’s reorganization of the agency last year. Soldner, who also chairs the National Joint Council of Food Inspection Locals, says remaining inspectors must now visit eight facilities — double the usual number — each day.

That’s not possible, she says, so it’s unclear how much food is legitimately earning that stamp of approval.

“Did that plant receive that daily inspection from inspection personnel? In my mind, that’s a huge question mark,” Soldner says.

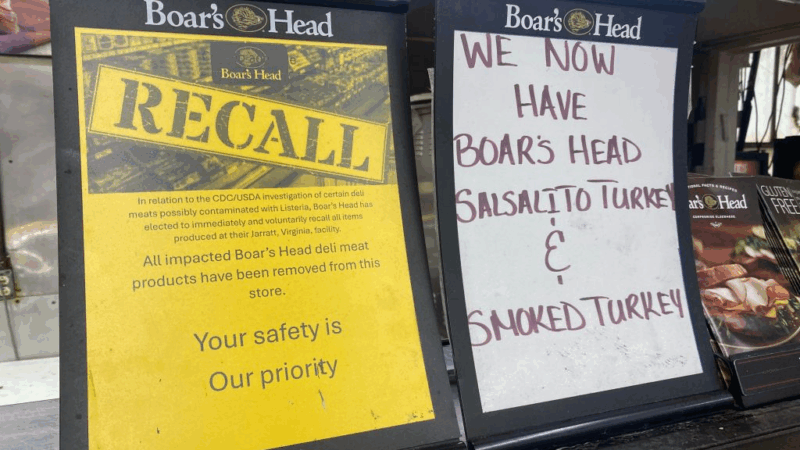

She says further staff retirements, hostility toward federal workers, and plummeting morale are creating conditions that make consumers more vulnerable to outbreaks of foodborne illness, like the deadly listeria contamination that hit Boar’s Head deli meats last year, killing 10 people and hospitalizing dozens.

“Do I foresee another Boar’s Head situation? Absolutely,” she says. “I worry about the public.”

Experts who study the nation’s food supply say the safety of everything we eat — from milk and macaroni to meat and lettuce — is called into question because of massive cuts by the Trump administration to the three federal agencies charged with monitoring it: the Food and Drug Administration, the Department of Agriculture, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Those three agencies coordinate and fund a lot of the complex work that makes up the country’s food safety surveillance system, while state and local regulators and inspectors conduct a lot of work on the ground.

Most produce is inspected by states, for example, though select samples are sent to one of the FDA’s national labs to test for pathogens like salmonella or E.coli. When a consumer falls ill, it’s often the local health officials who are first to know and then report cases to the CDC, which in turn traces the contamination to its sources and compiles data.

“Our federal food safety system is teetering on the brink of a collapse,” says Sarah Sorscher, a policy expert at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. She’s most concerned about the loss of expertise from recent job cuts.

But she also worries about policy moves like the administration’s rollback of new USDA food-safety rules set last August that would have limited the amount of salmonella in poultry in order for it to be sold. Instead, the agency said it is reevaluating the issue and whether salmonella regulations need updating at all.

In statements emailed to NPR, FDA and USDA said recent streamlining of their operations will not alter their commitment to food safety. USDA announced Tuesday that it boosted funds to reimburse states for food safety inspections by $14.5 million.

In a separate emailed statement, the USDA called its inspectors’ work “critical,” and said therefore inspectors were exempt from its hiring freeze, and its “front-line inspectors and veterinarians were not offered the opportunity to participate” in the agency’s second early retirement offer in April “because of the essential nature of their work.”

However, NPR reviewed emails sent from USDA officials urging inspectors to take the early retirement deal and confirming their eligibility for it, as well as a document listing eligible job categories, including consumer safety inspector and slaughterhouses inspectors.

Last month, the Trump administration also abruptly shuttered two of the FDA’s seven food testing labs in San Francisco and Chicago, according to several FDA staffers who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

The ensuing chaos delayed seafood inspections and routine produce testing, the FDA staffers, including microbiologists working in different labs, told NPR. Samples of lettuce or fruit had to be shipped in ice-packed containers to redirect them to other labs, where a shortage of staff and basic lab supplies such as plastic pipettes and other testing supplies, makes it difficult to triage the workload.

This month, the administration reopened the two labs, but Sorscher, who leads regulatory affairs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest, says damage has been done. “It’s as if you took a chainsaw and started cutting holes out of the walls of a house,” she says. “You can’t really point to the fact that the doors or windows are still there and say, ‘Don’t worry, the house is secure.'”

The CDC said in an emailed statement that its lab, surveillance and data collection work continues and that the agency “remains prepared to respond to, and work with states on those outbreaks.”

But many of the state and local food-safety programs historically funded by the CDC are at risk, says Steven Mandernach, executive director of the Association of Food and Drug Officials. Budgets and staffing have been cut at CDC, which affects how it supports local programs. The CDC, for example, typically funded staff to notify the public in the event of outbreaks, or to help remove dangerous products from shelves, as they did with lead-contaminated apple sauce pouches in 2023.

Mandernach says many states can no longer afford staff dedicated to public communications. So he worries about delayed warnings and less robust local tracking of cases that would affect national data.

“It could artificially make it look like, ‘Hey, food safety is great here,’ when the reality is we’re not looking for it as much,” he says.

Mideast clashes breach Olympic truce as athletes gather for Winter Paralympic Games

Fighting intensified in the Middle East during the Olympic truce, in effect through March 15. Flights are being disrupted as athletes and families converge on Italy for the Winter Paralympics.

A U.S. scholarship thrills a teacher in India. Then came the soul-crushing questions

She was thrilled to become the first teacher from a government-sponsored school in India to get a Fulbright exchange award to learn from U.S. schools. People asked two questions that clouded her joy.

Sunday Puzzle: Sandwiched

NPR's Ayesha Rascoe plays the puzzle with WXXI listener Jonathan Black and Weekend Edition Puzzlemaster Will Shortz.

U.S.-Israeli strikes in Iran continue into 2nd day, as the region faces turmoil

Israel said on Sunday it had launched more attacks on Iran, while the Iranian government continued strikes on Israel and on U.S. targets in Gulf states, Iraq and Jordan.

Trump warns Iran not to retaliate after Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is killed

The Iranian government has announced 40 days of mourning. The country's supreme leader was killed following an attack launched by the U.S. and Israel on Saturday against Iran.

Iran fires missiles at Israel and Gulf states after U.S.-Israeli strike kills Khamenei

Iran fired missiles at targets in Israel and Gulf Arab states Sunday after vowing massive retaliation for the killing of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei by the United States and Israel.