Hospitals are posting prices for patients. It’s mostly industry using the data

Republicans think patients should be shopping for better health care prices. The party has long pushed to give patients money and let consumers do the work of reducing costs. After some GOP lawmakers closed out 2025 advocating to fund health savings accounts, President Donald Trump introduced his Great Healthcare Plan, which calls for, among other policies, requiring providers and insurers to post their prices “in their place of business.”

The idea echoes a policy implemented during his first term, when Trump suggested that requiring hospitals to post their charges online could ease one of the most common gripes about the health care system — the lack of upfront prices. To anyone who’s gotten a bill three months after treatment only to find mysterious charges, the idea seemed intuitive.

“You’re able to go online and compare all of the hospitals and the doctors and the prices,” Trump said in 2019 at an event unveiling the price transparency policy.

But amid low compliance and other struggles implementing the policy since it took effect in 2021, the available price data is sparse and often confusing. And instead of patients shopping for medical services, it’s mostly health systems and insurers using the little data there is, turning it into fodder for negotiations that determine what medical professionals and facilities get paid for what services.

“We use the transparency data,” said Eric Hoag, an executive at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota, noting that the insurer wants to make sure providers aren’t being paid substantially different rates. It’s “to make sure that we are competitive, or, you know, more than competitive against other health plans.”

Poor compliance from hospitals

Not all hospitals have fallen in line with the price transparency rules, and many were slow to do so. A study conducted in the policy’s first 10 months found only about a third of facilities had complied with the regulations. The federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services notified 27 hospitals from June 2022 to May 2025 that they would be fined for lack of compliance with the rules.

The struggles to make health care prices available have prompted more federal action since Trump’s first effort. President Joe Biden took his own thwack at the dilemma, by requiring increased data standardization and toughening compliance criteria. And in early 2025, working to fulfill his promises to lower health costs, Trump tried again, signing a new executive order urging his administration to fine hospitals and doctors that didn’t post their prices.

CMS followed up with a regulation intended to up the fines and increase the level of detail required within the pricing data.

But so far, “there’s no evidence that patients use this information,” said Zack Cooper, a health economist at Yale University.

In 2021, Cooper co-authored a paper based on data from a large commercial insurer. The researchers found that, on average, patients who need a scan pass six lower-priced MRI providers on the way from their homes to an appointment for a scan. That’s because they follow their physician’s advice about where to receive care, the study showed.

Executives and researchers interviewed by KFF Health News also didn’t think opening the data would change prices in a big way. Research shows that transparency policies can have mixed effects on prices, with one 2024 study of a New York initiative finding a marginal increase in billed charges.

The policy results thus far seem to put a damper on long-held hopes, particularly from the GOP, that providing more price transparency would incentivize patients to find the best deal on their imaging or knee replacements.

Difficulties with price-shopping

These aspirations have been unfulfilled for a few reasons, researchers and industry insiders say. Some patients simply don’t compare services. And, unlike with apples — a Honeycrisp and a Red Delicious are easy to line up side by side — medical services are hard to compare.

For one thing, it’s not as simple as one price for one medical stay. Two babies might be delivered by the same obstetrician, for example, but the mothers could be charged very different amounts. One patient might be given medications to speed up contractions; another might not. Or one might need an emergency cesarean section — one of many cases in medicine where obtaining the service simply isn’t a choice.

And the data often is presented in a way that’s not useful for patients, sometimes buried in spreadsheets and requiring a deep knowledge of billing codes. In computing these costs, hospitals make “detailed assumptions about how to apply complex contracting terms and assess historic data to create a reasonable value for an expected allowed amount,” the American Hospital Association told the Trump administration in July 2025 amid efforts to boost transparency.

Costs vary because hospitals’ contracts with insurers vary, said Jamie Cleverley, president of Cleverley and Associates, which works with health care providers to help them understand the financial impacts of changing contract terms. The cost for a patient with one health plan may be very different than the cost for the next patient with another plan.

The fact that hospital prices might be confusing for patients is a consequence of the lack of standardization in contracts and presentation, Cleverley said. “They’re not being nefarious.”

“Until we kind of align as an industry, there’s going to continue to be this variation in terms of how people look at the data and the utility of it,” he said.

How industry uses the data

Instead of aiding shoppers, the federally mandated data has become the foundation for negotiations — or sometimes lawsuits — over the proper level of compensation.

The top use for the pricing data for health care providers and payers, such as insurers, is “to use that in their contract negotiations,” said Marcus Dorstel, an executive at price transparency startup Turquoise Health.

Turquoise Health assembles price data by grouping codes for services together using machine learning, a type of artificial intelligence. It is just one example in a cottage industry of startups offering insights into prices. And, online, the startups’ advertisements hawking their wares often focus on hospitals and their periodic jousts with insurers. Turquoise has payers and providers as clients, Dorstel said.

“I think nine times out of 10 you will hear them say that the price transparency data is a vital piece of the contract negotiation now,” he said.

Of course, prices aren’t the only variable that negotiations hinge on. Hoag said Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota also considers quality of care, rates of unnecessary treatments, and other factors. And sometimes negotiators feel as if they have to keep up with their peers — claiming a need for more revenue to match competitors’ salaries, for example.

Hoag said doctors and other providers often look at the data from comparable health systems and say, “‘I need to be paid more.'”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF.

Paul McCartney’s decade of transformation: From Beatles breakup to John Lennon’s murder

Man on the Run shows McCartney's effort to define himself outside The Beatles' shadow: "Paul making this documentary was a way of coming to terms with that whole period," says director Morgan Neville.

A Biden-era rule sought to stabilize child care. Why Trump wants it gone

The Trump administration has proposed repealing a Biden-era rule that required states to change how they pay out child care subsidies, citing the potential for fraud.

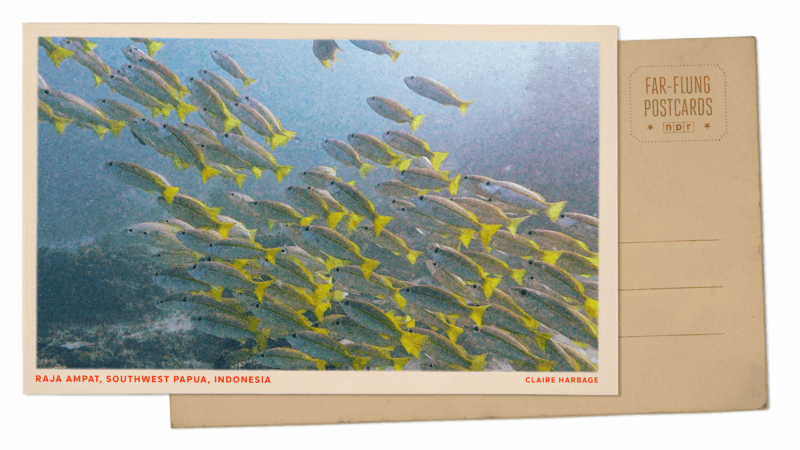

Greetings from Southwest Papua, which has some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity

The Raja Ampat islands in Indonesia's Southwest Papua province are a marine biodiversity hotspot and a divers' paradise.

Families remember U.S. reservists killed in Kuwait, members of an Iowa logistics unit

Four U.S. soldiers were killed in the Iran war on Sunday and IDed Tuesday by the Pentagon; two soldiers haven't yet been publicly identified. Their unit kept troops supplied with food and equipment.

Why supporting a shelter for women is now ‘kind of radioactive’

That's how researcher Beatriz Garcia Nice describes the new U.S. stance under the Trump administration to programs addressing gender-based violence.

Telehealth abortion is in the courts. Share your experience.

Mifepristone is facing another major legal challenge.