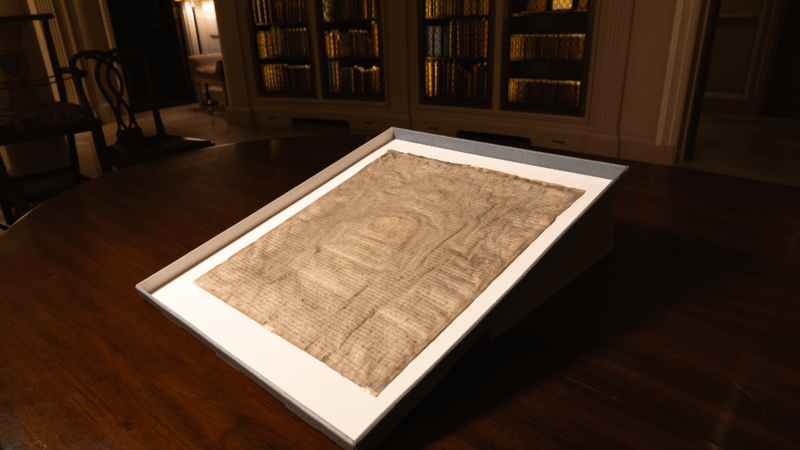

Harvard learned it has an authentic Magna Carta. In 1946, it paid less than $28 for it

It wasn’t exactly like the big reveal on the Antiques Roadshow. But one day in December 2023, David Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King’s College London, was searching through the digital archives of the Harvard Law Library when he clicked on a document that would become the biggest discovery of his career.

It had been labeled as a 1327 copy of the Magna Carta, “somewhat rubbed and damp-stained,” according to the archive’s description. But Carpenter knew almost immediately when he opened the document that it wasn’t as advertised: “What do I see before my eyes? For all the world [it] seemed to me an original of the 1300 Magna Carta.” He immediately thought, “Oh, my God, this isn’t known at all.”

It was a remarkable find not only for Carpenter, but for Harvard — especially since the university had paid a London bookseller just $27.50 (about $460 adjusted for inflation) for the document in 1946. An authentic Magna Carta sold in 2007 for $21.3 million.

The Magna Carta is one of the most important documents in history and deeply influenced the framers of the U.S. Constitution. First signed by England’s King John in 1215, it aimed to circumscribe the king’s power and establish the principle that even the monarchy is not above the law. It also guaranteed certain rights such as protections from arbitrary imprisonment and the right to due process.

But the document went through six different iterations throughout the 13th Century, the final one dating to 1300. “It is, in a way, the last Magna Carta … the final emphatic Magna Carta,” Carpenter says.

Searching through Harvard’s digital archives, there were a few giveaways that tipped Carpenter off that he was looking at an authentic copy. “In particular, the letter E of the ‘Eduardus,’ the king confirming the charter … looked very similar to the letter in the other originals” of the famous document, Carpenter says. “It clearly was Edward I confirming Magna Carta. And the date at the end was 1300.”

But his intuition still needed scholarly backing. Carpenter brought in a colleague, Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia and a fellow Magna Carta expert. “We combined forces to try and prove that we were right because, you know, first impressions can be misleading,” Carpenter says.

They contacted Harvard, requesting an ultraviolet scan so they could examine the document more closely. That’s when Jonathan Zittrain, head of the Harvard Law School library, first learned there was some interest in the document.

“There’s not always a ‘eureka’ moment, where it’s like ‘Ah, yes,’ ” Zittrain says. “You’ve got to tie together a number of threads to figure out the authenticity of something.”

“We were very fortunate that our British colleagues were in a position with their deep, deep expertise on exactly this topic, to look at a digitized copy of our holding,” he adds. “They could then do a bunch of preliminary work from their desks.”

Carpenter says while copies of the Magna Carta are abundant, originals are quite rare — with only about two dozen known to exist. There are only six other known copies of the 1300 version of the document like the one at Harvard.

Zittrain says it’s serendipity that the document’s authenticity was ever discovered — one that “nobody might have thought was in the cards.”

He credits not only Carpenter and Vincent, but Harvard’s decision to digitize their archives so that the public at large can access them. “And of course,” Zittrain adds, “it makes you wonder, gosh, what else do we have between the couch cushions?”

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

U.S. states take steps to guard against any potential threat from Iran

Iran has made prior attempts to launch terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, but all have been thwarted in recent years. States are bracing for a heightened threat after the war.

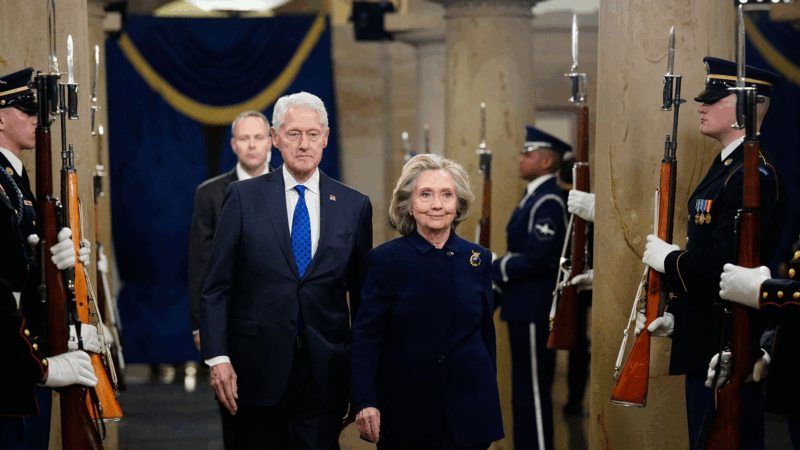

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.