From gifting a hat to tossing them onto the rink, a history of hat tricks in sports

The men’s hockey tournament at the 2026 Milan Cortina Games is underway and many fans are hoping to see the exciting feat of scoring three goals in a single game, better known as a hat trick.

“ I’m curious to see over in Italy for the Olympics, if we’ll see a hat trick to begin with, and then second will people throw their hats?” said Ty Di Lello, a hockey historian based in Winnipeg, Canada.

The international sporting event will mark the return of National Hockey League players after a 12 year absence. It comes as the NHL set a new record for the most hat tricks in a single month this January.

Hat tricks have a rich history in the world of hockey, but it didn’t start there. In fact, the phrase originated in cricket and spread to many sports, including soccer, darts and horse racing.

In this installment of NPR’s Word of the Week series, we trace hat trick’s some 150-year-history and why it’s particularly special on a hockey rink.

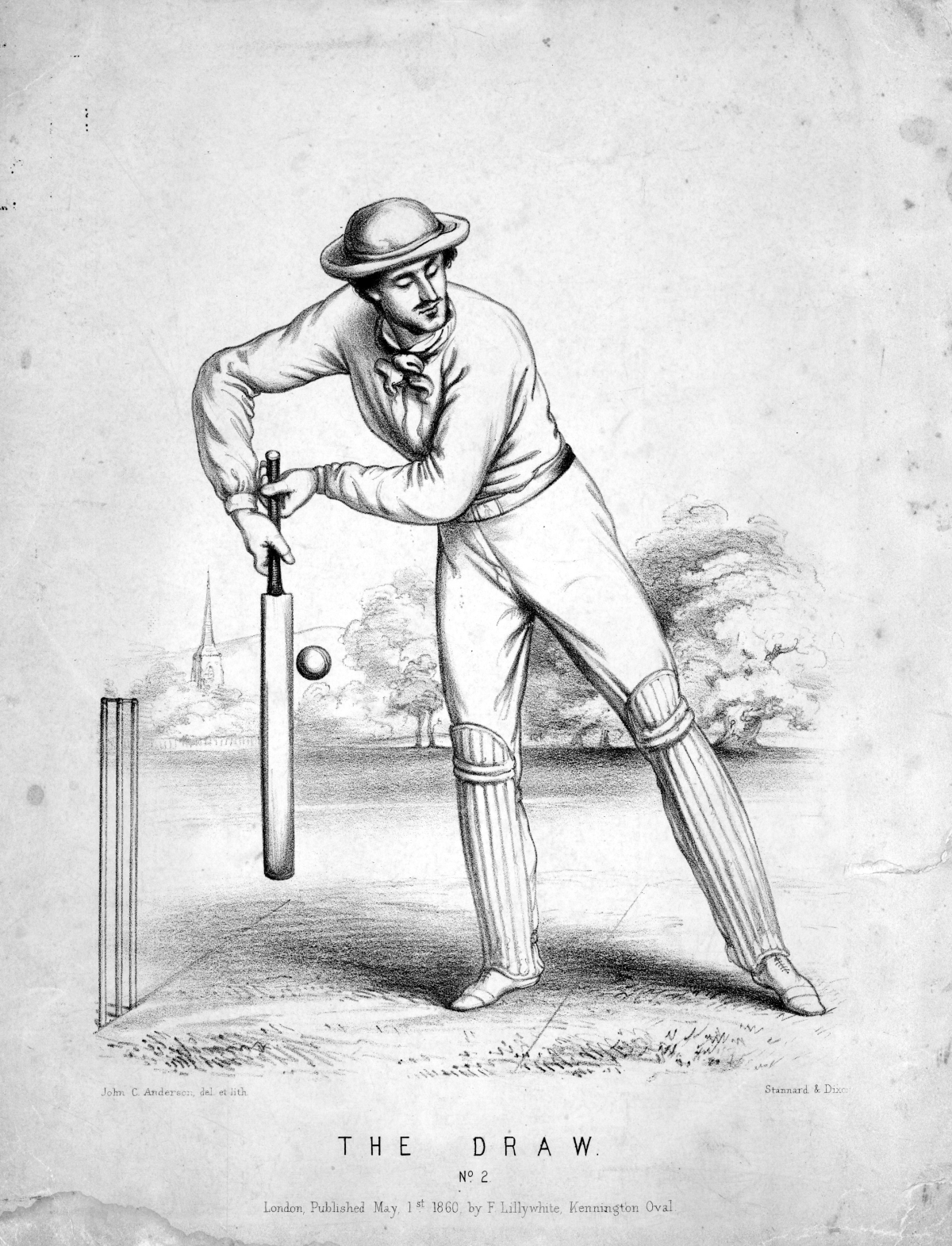

How ‘hat trick’ was coined in cricket

In cricket, a hat trick refers to the dismissal of three batters by the same baller with three successive balls. Rodney Ulyate, a spokesperson for the Association of Cricket Statisticians and Historians, compares it to when a pitcher in baseball gets three consecutive strikeouts.

“I gather it’s a very common thing in baseball. I think you call it a no hit inning,” he said. “But in cricket, trust me, it is vanishingly rare.”

Now, it remains unclear who coined hat trick, but its origin did indeed involve headwear.

In the 19th century, there were reports in British newspapers of cricketers being given a hat after achieving what is now known as a hat trick. Ulyate said at the time, cricketers earned very little for competing, so their pay was often supplemented with material prizes like bats, balls and watches.

By 1874, hat trick was the common term for taking three wickets in three consecutive balls — beating out expressions “hat feat” and “bowling a gallon.” The latter stemmed from some cricketers being awarded a gallon of beer.

“ I must say that given the quantities of beer that cricketers are notorious for drinking … it’s surprising that ‘bowling a gallon’ didn’t take off,” Ulyate said.

It’s also a mystery why “cap trick” didn’t catch on since cricket players commonly wore caps, Ulyate added.

Over the years, cricketers were gifted all kinds of headwear, from a straw hat to a green felt, feathered Tyrolean hat. While the phrase hat trick remains in cricket, hat prizes themselves began to disappear in the early 1900s, during the interwar period.

“It’s pretty hard to imagine today that any millionaire cricketer would be very impressed by the gift of a hat,” Ulyate said.

Hat trick’s special place in hockey

In hockey, a hat trick not only refers to scoring three goals or more in a single game, but it’s often followed by spectators hurling their beanies, caps and other headwear onto the rink.

Like in cricket, the phrase hat trick in hockey also began with a free hat. But who exactly introduced the term? Well, that’s up for debate between two hat shops in Canada — Sammy Taft: World Famous Hatter store in Toronto and Henri Henri in Montreal. In both origin stories, the owners began gifting hockey players a hat from their store as a marketing opportunity.

“Once that connection between three goals and hats was established, fans basically took it over themselves,” said Di Lello who has written about hat tricks.

“That probably started happening gradually in the late ’40s and ’50s as hockey crowds got bigger and traditions started forming,” he added.

Marie Lansiaux, assistant hatter at Henri Henri, said at the time, spectators who flung their hats onto the ice would go retrieve their headwear at a counter after the game.

That gave the owner of Henri Henri another idea: hand out cards that can be tucked into a hat’s sweatband. On one side, the card listed the schedule of the Montreal Canadiens games, while the other side read “Like Hell it’s yours! Put it back and try another.”

“And you could write your name on the card and prove that it was your hat, so that way nobody could pinch your hat out of the boxes,” Lansiaux said.

Nowadays, the tossed hats are given to the player who scored the hat trick, or they are put on a display in the foyer of the arena, according to Philip Pritchard, vice president and curator of the Hockey Hall of Fame.

“It’s a great unwritten rule in the game of hockey,” he said.

Pritchard added that while other sports have abandoned the free hat tradition, the fact that hockey fans have kept it alive speaks to what he loves most about the game: its reverence to tradition.

“The hat trick is just another part of it and another story on why the human side of the game really shows in the game of ice hockey,” he said.

Paul McCartney’s decade of transformation: From Beatles breakup to John Lennon’s murder

Man on the Run shows McCartney's effort to define himself outside The Beatles' shadow: "Paul making this documentary was a way of coming to terms with that whole period," says director Morgan Neville.

A Biden-era rule sought to stabilize child care. Why Trump wants it gone

The Trump administration has proposed repealing a Biden-era rule that required states to change how they pay out child care subsidies, citing the potential for fraud.

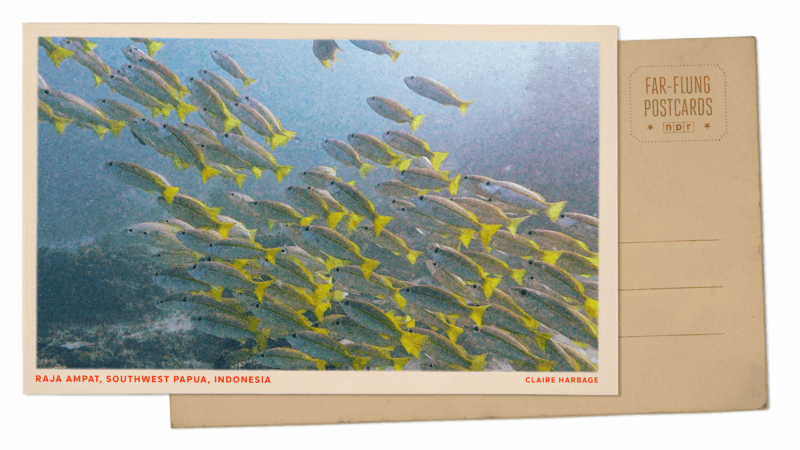

Greetings from Southwest Papua, which has some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity

The Raja Ampat islands in Indonesia's Southwest Papua province are a marine biodiversity hotspot and a divers' paradise.

Families remember U.S. reservists killed in Kuwait, members of an Iowa logistics unit

Four U.S. soldiers were killed in the Iran war on Sunday and IDed Tuesday by the Pentagon; two soldiers haven't yet been publicly identified. Their unit kept troops supplied with food and equipment.

Why supporting a shelter for women is now ‘kind of radioactive’

That's how researcher Beatriz Garcia Nice describes the new U.S. stance under the Trump administration to programs addressing gender-based violence.

Telehealth abortion is in the courts. Share your experience.

Mifepristone is facing another major legal challenge.