Fire-making materials at 400,000-year-old site are the oldest evidence of humans making fire

It’s easy to take for granted that with the flick of a lighter or the turn of a furnace knob, modern humans can conjure flames — cooking food, lighting candles or warming homes.

For much of our history, archaeologists think, early humans could only make use of fire when one started naturally, like when lightning struck a tree. They could gather burning materials, move them and sustain them. But they couldn’t start a fire on their own.

At some point, somewhere, that changed. An early human discovered that by rubbing two sticks together or striking the right kinds of rocks together, at the right angle, with the right force, they too could create fire.

Archaeologists have long wondered when that discovery happened. A new study, published in the journal Nature, provides the earliest evidence yet from a site in eastern Britain.

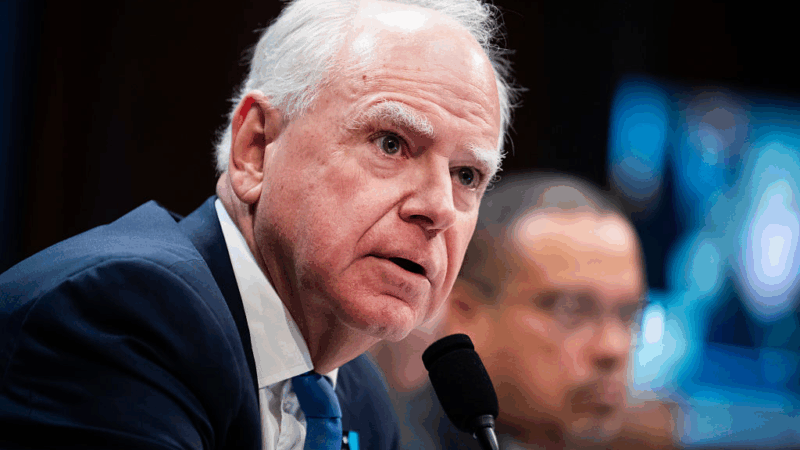

“This is a 400,000-year old site where we have the earliest evidence of [humans] making fire — not just in Britain or in Europe — but anywhere else in the world,” said Nick Ashton, an archaeologist at The British Museum and one of the study’s authors.

The discovery suggests early humans were making fire more than 350,000 years earlier than previously known.

“For me, personally, it’s the most exciting discovery of my 40-year career,” Ashton said.

What makes the site so unique is that Ashton and his colleagues found the raw materials for making fire — fragments of iron pyrite alongside fire-cracked flint handaxes in what looks like a hearth. A geological review found that pyrite is incredibly rare in the area, suggesting that early humans brought it to the site with the intention of using it to start fires.

“As far as we know, we don’t know of any other uses for pyrite other than to make sparks with flint to start fires,” said Dennis Sandgathe, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University, who was not involved in the new study. “And of all the dozens and dozens of sites across Eurasia and into Africa that we’ve excavated that have fire residues in them, nobody’s discovered a piece of pyrite before.”

The ability to make fire, archaeologists agree, is one of the most important discoveries in human history. It allowed early humans to ward off predators, to get more nutrients out of food and to settle inhospitable climates.

The ability to sit around a campfire at night would have also been a catalyst for social and behavioral evolution.

“By having fire it provides this kind of intense socialization time after dusk,” said Rob Davis, an archaeologist at The British Museum and co-author of the study. “And that’s going to be a really important thing for other developments like the development of language, development of storytelling, early belief systems. And these could have played a critical part in maintaining social relationships over bigger distances or within more complex social groups.”

Davis and his co-authors don’t know the identity of the people who used the site. But less than a hundred miles to the south, archaeologists have found fragments of a skull from roughly the same time period that could have belonged to a Neanderthal. “So we assume that the fires at [the new study’s site] were being made by early Neanderthals,” said Chris Stringer, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in the UK and one of the study’s co-authors.

It’s possible that other early humans, including Homo sapiens, had the ability to make fires too, Stringer said. But it’s difficult to say with any degree of certainty.

Sandgathe, who’s investigated early humans’ use of fire for decades, said the discovery is very significant but he cautioned it shouldn’t be used to make broad generalizations of early human fire use.

Modern humans long assumed that the discovery of how to make fire was such an important technology that once it was found, it would have spread rapidly across the Old World like, well, fire — and from then on everybody everywhere would have been using it.

“We now realize that was way too simplistic,” he said. What’s more likely, Sandgathe said, is that different groups of early humans accidentally discovered how to make fire at different times. The knowledge may have spread or it may have been lost.

“It’s just not a linear story,” he said. “It’s a complex story of many fits and starts, over here and over there — and many millennia where nobody knew how to make fire until it was discovered again.”

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

Billy Joel famously sang, we didn’t start the fire – it was always burning since the world’s been turning. But that’s not entirely true. Humans do start fires to cook, to heat, to gather around. Scientists have long wondered when we first learned how. NPR’s Nate Rott reports archaeologists have found the earliest example yet.

NATE ROTT, BYLINE: It’s easy to take for granted that with the flick of a thumb…

(SOUNDBITE OF LIGHTER SPARKING)

ROTT: …Or the turn of a knob…

(SOUNDBITE OF STOVETOP IGNITING)

ROTT: …You, a five-fingered mammal, can create flames, providing…

ROB DAVIS: Warmth, protection from predators, light, the ability to cook food.

ROTT: Rob Davis is an archaeologist at the British Museum.

DAVIS: It provides time after dusk, so extends the waking day.

ROTT: …Giving people today and millennia ago – Davis’s specialty – more time to sit around communally to tell tales, share ideas or beliefs.

DAVIS: So a really important development for human evolution.

ROTT: Archaeologists believe that humans and our ancestors have used fire for more than a million years, but for most of that time, early humans couldn’t create it. They depended on nature to start one, like lightning striking a tree.

DAVIS: But it’s not something you could have relied upon. Wildfires are seasonal. They’re not necessarily predictable. So it’s only once you can actually make fire that it can become kind of a, you know, a daily part of the routine.

ROTT: Which is why Davis and his co-authors – including Nick Ashton, from the British Museum – were so excited to find fragments of iron pyrite at a site in Britain where early humans were using fire more than 400,000 years ago. Iron pyrite – for you non-Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts out there – can be used with flint to make sparks. And Ashton says, It’s incredibly rare near the location they looked at. So…

NICK ASHTON: We think humans brought pyrite to the site with the intention of making fire.

ROTT: Which would make the site described in the journal Nature the earliest known example of early humans making fire anywhere in the world. And they suspect it was Neanderthals.

ASHTON: For me, personally, it’s the most exciting discovery of my 40-year career.

DENNIS SANDGATHE: We don’t know of any other uses for pyrite other than to make sparks with flint to start fires.

ROTT: Dennis Sandgathe, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University, was not involved in the new study.

SANDGATHE: And of all the dozens and dozens of sites across Eurasia and into Africa that we’ve excavated that have fire residues in them, nobody’s ever found a piece of pyrite before.

ROTT: Sandgathe says it’s hard to make broad generalizations about early humans’ knowledge of fire based off of one site. It might have just been one group or one individual that knocked rocks together and accidentally discovered fire.

SANDGATHE: But then glacier comes along and populations collapse, and that technology is lost.

ROTT: …Only for it to be discovered again. The point is, the story of humans and fire is not linear, Sandgathe says, but it’s one that we continue to benefit from today. Nate Rott, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF SONG, “WE DIDN’T START THE FIRE”)

BILLY JOEL: (Singing) We didn’t start the fire. It was always burning since the world’s been turning. We didn’t start the fire.

U.S-Israeli strikes continue across Iran, Iranian drones hit Azerbaijan

The U.S. and Israel said they conducted new strikes inside Iran overnight, targeting ballistic missile launchers. Iran claimed it struck a U.S. oil tanker in the northern Persian Gulf.

In lawsuit, Minnesota accuses Trump administration of ‘weaponizing’ Medicaid funding

The federal government said the state should do more to fight fraud and is holding back funds. Minnesota officials say the attack is unfair as the state's fraud rate is well below national averages.

Wall Street is betting on tariff refunds after Supreme Court ruling

When the Supreme Court struck down many of President Trump's tariffs, it left importers wondering how long they'd have to wait to get their money back. Hedge funds are offering to help out.

A run for their money: Young candidates rival older incumbents in midterm fundraising

As a growing crop of young candidates challenge longtime Democratic incumbents, some are not just breaking through in the money race, but outraising their opponents altogether.

Announcing the 2025 NPR College Podcast Challenge Honorable Mentions

Here are some of the best entries in NPR's 2025 College Podcast Challenge.

When ICE came, Minneapolis created underground health networks. Should other cities?

The Trump administration's immigration crackdown in Minneapolis forced some families into hiding and catalyzed informal medical networks to deliver critical health care services inside homes.