Final Destination still works — here’s why

Many of the fears that horror movies exploit are buried deep, because they are fears of things that probably won’t happen. You’re statistically unlikely to die in a home invasion, or at the hands of a killer in a mask, or because you angered a homicidal doll, or because you unleashed an ancient curse.

The Final Destination franchise, including the new hit Final Destination Bloodlines, is a little different. As to the specifics, sure: You probably won’t die because a sign falls on you, or because a barbecue explodes, or because you get hit by a bus while you’re in the middle of an impassioned argument. But those things are not quite the fears that the Final Destination movies are about. They’re about a different fear: You’re gonna die sooner or later, and there’s nothing you can do about it. And unlike the homicidal doll, the ancient curse, or the home invasion, that fear? Well, that one is spot on, and it’s not just likely — it’s certain in life just as much as in the movies. You don’t know exactly when or how, but it’s going to happen. Worry about it or don’t; it’s going to happen all the same.

If you’re not familiar, the basic structure of a Final Destination movie, of which there have now been six, is usually this: A group of people somehow escape a disaster that they were otherwise going to experience, often because someone has a premonition. In the first movie, for instance, a group of students gets off a plane right before it takes off and explodes. Then, they discover that Death is still looking for them, because they were “meant” to die. One by one, generally in the order they were originally supposed to die, they are picked off in various grisly ways — despite, in some cases, knowing Death (which becomes a character of sorts in this world) is coming and trying to keep it from happening.

There are complications and rules about whether it’s possible to delay Death, stop it, or be “skipped” in the order. There are rules about how it happens — it’s not that some malicious person kills you or even negligently drops something on you. It just happens. Many Final Destination deaths are Rube Goldberg machines of disaster, where one tiny event sets off another, and another, and another, until … squish. (Or boom, or splat, or crunch.)

These films have never been mega-blockbusters; they don’t make Marvel money. And there hadn’t been one since 2011 until Final Destination Bloodlines. It’s not a franchise that dominates the zeitgeist or makes its actors into instant A-listers. But it is sturdy, and it is fun. I recently watched a 40-minute YouTube video, posted by Entertainment Weekly, in which one of the producers goes through all the death scenes in the first five movies. He explains how they conceived and shot the sequences, and in some cases he even reveals how a death was described — sometimes hilariously — in the script.

I think watching that video clarified the cleverness of Final Destination’s premise for me, because a lot of these scenes are very intentionally funny. Gross-funny, like “that’s gotta hurt,” and gory-funny, like “oh look, he was bisected and his top half is still alive.” The effect on the whole is something like, “Everybody’s going to die, and bodies are weird and gross, but hey, we might as well have fun.”

In Final Destination Bloodlines, there’s an important scene with Tony Todd, who has appeared as coroner William Bludworth in several Final Destination movies and who died in November of 2024. Todd is a horror icon, most notably because he played Candyman, although he also had a long and varied career as a theater, screen and voice actor. In Bloodlines, Bludworth’s role is what it has been in these movies before: He can explain Death and how it works, and what it wants. In this final appearance, he tells the doomed kids what he’s learned about its inevitability. The directors told Variety that they asked Todd, who they knew was ill, to speak unscripted, which he did. It’s quite a scene. He spoke about making the most of the life you have, and about the unpredictability of the timing, but not the fact, of your death. It’s genuinely moving, even though the film kills people in the wacky and convoluted ways fans expect.

Maybe the best explanation I can offer for the success of Final Destination is this: It’s funny ’cause it’s true. When you die, you probably won’t go squish, but you’ll go, and so will everybody else. And somehow, that inevitability — even though it’s characterized here as otherworldly stalking by a sentient Death rather than as simple biological reality related to, again, the fact that bodies are weird and gross — becomes amusing and therefore manageable. So even knowing it’s scary: take the trip, ride the roller coaster, go to the restaurant that teeters high above the city.

Not because you can cheat death forever, but because you can’t.

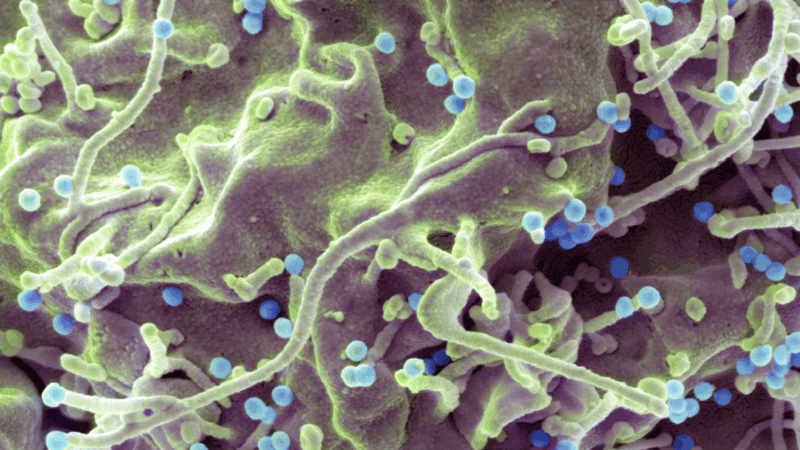

A new one-a-day-pill holds promise for HIV’s ‘forgotten population’

It's designed to take the place of complicated, multiple drug regimens that many people with HIV need to follow. And it's also beneficial because the HIV virus is always evolving.

For filmmaker Chloé Zhao, creative life was never linear

Director Chloé Zhao used meditation, somatic exercises and dance to inspire the cast and crew of this Oscar-nominated story about William Shakespeare's family.

10 new books in March offer mental vacations

March is always a big one for books – this year is no different. We call out a handful of upcoming titles for readers to put on their radars — offering a good alternative to doomscrolling.

Sen. Chris Coons, D-Del., talks about the war with Iran and upcoming war powers vote

NPR's A Martínez asks Delaware Democrat Chris Coons, a member of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, about the war with Iran.

The candy heir vs. chocolate skimpflation

The grandson of the Reese's Peanut Butter Cups creator has launched a campaign against The Hershey Company, which owns the Reese's brand. He wants them to stop skimping on ingredients.

Scientists make a pocket-sized AI brain with help from monkey neurons

A new study suggests AI systems could be a lot more efficient. Researchers were able to shrink an AI vision model to 1/1000th of its original size.