Congress moves to loosen toxic air pollution rules

Congress has voted to undo a Clean Air Act regulation that strictly controls the amount of toxic air pollutants emitted by many industrial facilities like oil refineries, chemical plants, and steel mills.

The decision represents the first time since the creation of the landmark environmental law that Congress has rolled back its environmental protections.

Environmental groups and public health advocates condemned the vote, saying the rollback could cause higher pollution and harm human health.

“What that will mean for Americans is more hazardous air pollution across the country,” says John Walke, an environmental health expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group.

“These are pollutants that cause cancer and birth defects and brain damage,” Walke says.

The vote targets a rule finalized late in the Biden administration, which re-imposed tight regulations on facilities that emit seven so-called “super pollutants” like mercury, a dangerous form of lead, and dioxins. The rules regulating those seven pollutants, along with more than 180 others, were first imposed in the 1990s, but were rolled back during the first Trump administration.

The House approved the resolution early Thursday morning, following a Senate vote in favor of changing the rule earlier this month. Under the Congressional Review Act, lawmakers can review EPA regulations within a short window after their implementation and reverse them with a simple majority vote. President Trump has signaled he is likely to sign the bill when it arrives on his desk.

The move is part of a larger effort by the Trump administration to roll back environmental and public health regulations. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin announced in March that he intends to re-evaluate other regulations like the one Congress just voted to change, which is related to a section of the Clean Air Act that deals with Hazardous Air Pollutants.

The agency, Zeldin says, is embarking on the “biggest deregulatory action in U.S. history,” which he says is meant to lower the cost of operating businesses in the U.S. while fulfilling the agency’s core mission of protecting the environment. Zeldin also aims to target other parts of the Clean Air Act, like the rules regulating mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants and the National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

Industry groups like the National Association of Manufacturers welcomed Congress’s decision. In a December open letter to president-elect Trump, the group had called for a review of EPA’s rules regarding hazardous air pollutants, calling them “technically unachievable and economically infeasible.”

“By eliminating the misguided “Once-in, Always-in” rule, we can reduce compliance costs for manufacturers while incentivizing better environmental outcomes,” says Chris Phalen, vice president of domestic policy at NAM.

But environmental and public health experts warn the change could result in higher pollution levels in communities that neighbor industrial facilities like “oil refineries, chemical plants, coke ovens, aluminum plants, lead smelters, things of that nature. We call it the worst of the worst list,” says Walke. The facilities are largely concentrated in parts of the country with high industrial activity, like the Gulf Coast and parts of Appalachia.

“Once in, always in”

The rule concerns the regulation of seven particularly hazardous air pollutants like dioxins and mercury. Such pollutants move through the air but also accumulate in soil, dust, and people’s bodies; several are known to cause cancer, neurological issues, and birth defects even at very low exposure levels.

Rules regulating those seven air toxic pollutants, along with more than 180 others, have been in place since 1990 when Congress passed a major amendment to the Clean Air Act that greatly increased its specific regulatory powers. It tasked EPA with tightly regulating what it called “major sources” of dangerous air pollutants—facilities that emitted more than 25 tons (50,000 pounds) of the hazardous pollutants a year, or 10 tons of any single one. Facilities that emitted less pollution, called “area sources,” would be much more lightly controlled.

The regulation Congress targeted concerns which facilities count as “major sources.”

Since the 1990s, EPA’s policy has stipulated that any “major source” would remain categorized as such, even if it cut pollution levels to below the certain thresholds—a policy known as “Once in, always in.” The policy intended to keep toxic air pollution levels not just lower, but as low as possible.

But under the first Trump administration, the EPA allowed major sources to re-categorize if they had reduced their dangerous emissions. Last year, the EPA under Biden undid part of that change, once again expanding the number of facilities covered.

Since the rule change is relatively recent, Republicans in Congress could now challenge it using the Congressional Review Act. The result would be a more durable change to the law. Under the rules of the CRA, “EPA can no longer do a similar rule or a rule that is substantially similar,” says Carrie Jenks, an environmental law expert at Harvard University. To revisit the HAP rule once again, EPA would have to come up with a new, different argument for why to keep major sources classified as major.

The advocacy group EarthJustice estimated that the change would allow roughly 1,800 industrial facilities, like steel mills or chemical factories, to apply to be taken off the “major sources” list.

Pollution risks

Exposure to even small levels of the seven super-toxins is so dangerous, say environmental and public health experts, that releasing major sources from the strict regulations and controls under the “major sources” framework could lead to higher levels of pollution exposure in nearby communities.

“Picture some of the communities in the industrial Midwest, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio or along the Gulf in Texas and Louisiana,” where there are many emitters of toxic air pollutants concentrated in one area, says former Biden-era assistant EPA administrator Joseph Goffman.

Even if each of them were below their individual emissions limit, the total amount of pollution in the air nearby would be high, he explains. The more stringent regulations, he says, help to keep that total amount of pollution low — and safer for people nearby.

Ultimately, what matters to human health is not how much each facility emits but how much is released altogether in a specific region, Goffman says — and the EPA’s more strict regulations intended to keep that overall level low.

“It’s so important to keep a focus on the total amount of toxic air pollution that the people who live there are breathing, and not just on the individual sources level of pollution,” he says.

PHOTOS: Your car has a lot to say about who you are

Photographer Martin Roemer visited 22 countries — from the U.S. to Senegal to India — to show how our identities are connected to our mode of transportation.

Looking for life purpose? Start with building social ties

Research shows that having a sense of purpose can lower stress levels and boost our mental health. Finding meaning may not have to be an ambitious project.

Danish military evacuates US submariner who needed urgent medical care off Greenland

Denmark's military says its arctic command forces evacuated a crew member of a U.S. submarine off the coast of Greenland for urgent medical treatment.

Only a fraction of House seats are competitive. Redistricting is driving that lower

Primary voters in a small number of districts play an outsized role in deciding who wins Congress. The Trump-initiated mid-decade redistricting is driving that number of competitive seats even lower.

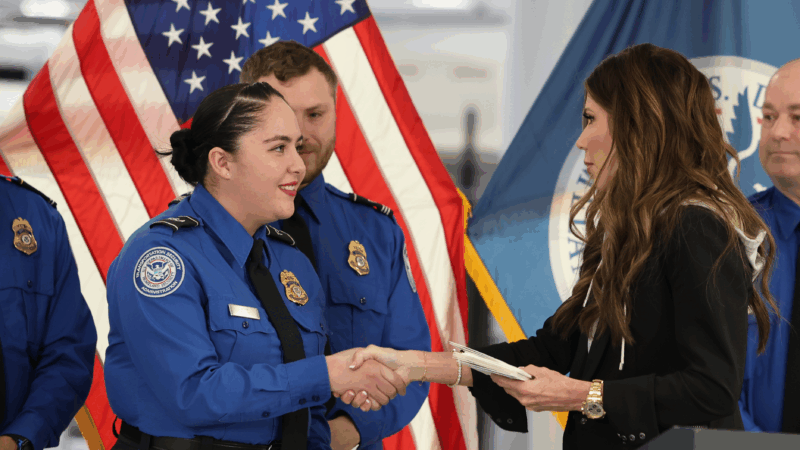

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."