Children in a mental health crisis can spend days languishing in the ER

Children who go to emergency departments in a mental health crisis and need to be hospitalized often end up stuck there for days, a new study finds. That happens in roughly one in ten of all mental health emergency visits for children enrolled in Medicaid across the country.

The most common mental health crises that led to such extended stays, or boarding, were depressive disorders and suicidal thoughts and attempts, according to the study published in JAMA Health Forum.

“So a child shows up at an emergency department with a mental health condition, [and] about one in ten times, they’re staying for three days or longer,” says lead study author John McConnell, director of the Center for Health Systems Effectiveness at Oregon Health and Science University.

McConnell and his colleagues also found that in a handful of states, including North Carolina, Florida and Maine, as many as 25% of mental health visits led to kids boarding at the emergency department for 3-7 days.

The findings aren’t surprising, says Dr. Jennifer Havens, chair of the department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

“But having data like this is very important to see the effect across the country,” she adds. Havens was not involved in the study.

Boarding in the emergency department has been a growing issue across the nation for decades, but the rise has been particularly dramatic in recent years for pediatric mental health cases.

“As the children’s behavioral health crisis nationwide has increased, states have not been able to keep up with behavioral health systems,” says Dr. Rebecca Marshall, an associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at OHSU, who also wasn’t involved in the new study.

Though the study looked only at Medicaid claims, the problem happens for children on private health insurance, as well.

“We really have struggled to build capacity over time to increase the number of inpatient beds,” she says. “And so often what happens is kids will come into the hospital, they need an inpatient psychiatric bed and there isn’t one available. So then they wait until a child in one of the psychiatric units discharges and a bed becomes available.”

Many states have a shockingly low number of psychiatric beds for kids, says Marshall. For example, Oregon has only 38 beds for highest need pediatric psychiatric cases. “And then we have less than 200 residential beds, and that’s a lower acuity treatment program that tends to be longer term.”

“There’s an enormous problem across the country with a lack of access to mental health services, both on the [inpatient and] outpatient side,” says Havens. Adequate outpatient services can prevent kids with mental health conditions from reaching a crisis point.

Without adequate outpatient and inpatient mental health care options, families are more likely to take their child to an ER if the child is in a mental health crisis.

But “what they find when they go to the emergency department is that there often isn’t any available care,” says Marshall. “There’s nothing immediate.”

Most ERs don’t even have a child and adolescent psychiatrist, says Havens, “because we’ve just never invested in the resources to have this kind of service for kids.”

And when children in mental health crises end up stuck in ERs for days, their symptoms can worsen even if there’s a psychiatrist on staff.

Most of these children boarding in an ER end up stuck in “one small room,” says Marshall, sometimes a windowless room. “They’re not able to leave the room. They can’t exercise. They’re not able to interact with other kids, which is a really important part of development. And often there are not any kind of additional therapeutic activities that you would find in an inpatient unit.”

“I’m not sure what the right words are, but, [it’s] really challenging, heartbreaking situation for families that have a child and they’re trying to kind of find a place to stabilize them, and they’re stuck in the emergency department,” says McConnell.

Tuskegee men’s basketball coach handcuffed after intervening in postgame incident

A statement from civil rights attorney Harry Daniels' office said Benjy Taylor was concerned about Morehouse football players who “were acting aggressively” toward Tuskegee players and their parents during postgame handshakes on Saturday.

U.S. sledder Katie Uhlaender appeal denied, won’t race at Milan Cortina Olympics

International officials say a point-rigging scheme denied American Katie Uhlaender a shot to compete in the Milan Cortina Olympics. But a sports tribunal based in Switzerland says it can't intervene.

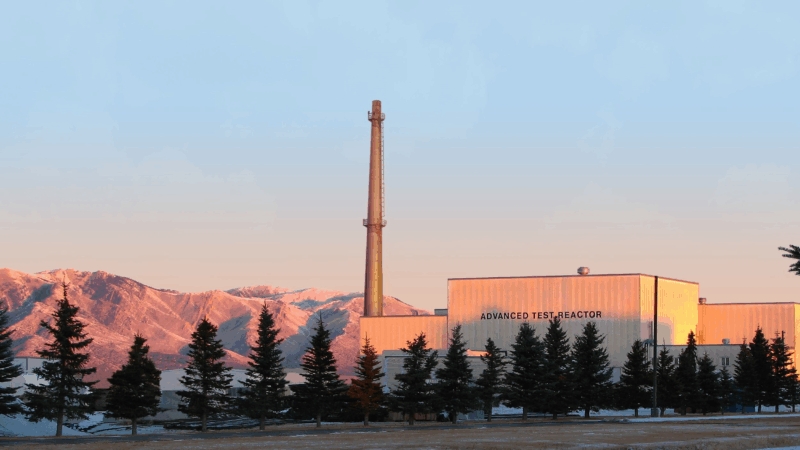

The Trump Administration exempts new nuclear reactors from environmental review

The announcement comes just days after NPR revealed the administration had secretly rewritten safety and environmental standards.

The ‘Melania’ movie audience: Older white women

The pricey Amazon documentary did well in areas like Dallas, Tampa, Phoenix, Houston, Atlanta and West Palm Beach. Amazon says a docuseries is also on the way.

Trump says he’s closing the Kennedy Center for renovations. We have questions

After President Trump announced plans for a "Complete Rebuilding" of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., what exactly did he mean, and what does it mean for the arts?

A major census test faces cutbacks — with postal workers tapped to help count

The Trump administration has shrunk the number of locations for this year's field test of the 2030 census and added plans to test replacing temporary census workers with U.S. Postal Service staff.