Can the prescription drug leucovorin treat autism? History says, probably not

At a press conference in late 2025, federal officials made some big claims about leucovorin, a prescription drug usually reserved for people on cancer chemotherapy.

“We’re going to change the label to make it available [to children with autism spectrum disorder],” said Dr. Marty Makary, commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration. “Hundreds of thousands of kids, in my opinion, will benefit.”

The FDA still hasn’t made that label change.

Since Makary’s remarks, though, more than 25,000 people have joined a Facebook group called Leucovorin for Autism. Most members appear to be parents seeking the drug for their autistic children.

Also since the press conference, some doctors have begun writing off-label prescriptions for autistic children, against the advice of medical groups including the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The buzz about leucovorin has led to a shortage of the drug. In response, the FDA is temporarily allowing imports of tablets that are made in Spain and sold in Canada, but not approved in the U.S.

All of this is part of a familiar cycle for Dr. Paul Offit, who directs the vaccine education center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Offit says he realized years ago that leucovorin’s popularity was far ahead of the science.

“I saw it for what it was, which was yet the next magic medicine to treat autism, in a long line of magic medicines to treat autism that haven’t worked,” Offit says.

Offit has chronicled the rise and fall of many of those products in his books and blog posts.

“First it was secretin, an intestinal hormone,” he says. “Then it was Lupron, chemical castration, antibiotics, megavitamins, nicotine patches, and my personal favorite, which is raw camel’s milk.”

Leucovorin is likely to find a place on that cautionary list, Offit says, adding that the FDA has failed to protect the public from an autism remedy that “clearly hasn’t been well tested to be effective.”

A deficiency discovered

The rationale for leucovorin’s use in autism rests on its link to a form of vitamin B called folate — and to a condition called cerebral folate deficiency.

Folate is a dietary nutrient that is critical to brain development. Children whose brains don’t get enough of it are prone to seizures, muscle weakness, cognitive impairment and — in some cases — autism.

People with cerebral folate deficiency have normal levels of folate in the bloodstream, but low levels in the brain.

One cause of cerebral folate deficiency is a group of rare genetic mutations that were discovered starting in the 1990s. These mutations disable proteins needed to take folate from the blood and carry it into the cerebrospinal fluid — the liquid that surrounds the spinal cord and the brain.

In the early 2000s, scientists began finding evidence that cerebral folate deficiency could also be caused by the body’s own immune system.

Animal studies showed that immune cells sometimes produced antibodies that acted like those rare genetic mutations to prevent folate in the bloodstream from reaching the brain.

A link to autism?

A 2005 study in The New England Journal of Medicine suggested a link between cerebral folate deficiency and autism.

The study involved 28 children being treated by a doctor in Germany for a range of developmental disorders, including autism. All of the children had low levels of folate in their cerebrospinal fluid.

The doctor in Germany initially didn’t know why the folate levels were low, says Edward Quadros, a co-author of the study and a research professor at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn.

“So he contacted us and asked, ‘Could this be an autoimmune disorder?’ ” Quadros says. In other words: Was the immune system in these children making an antibody that could prevent folate in the bloodstream from reaching the brain?

Quadros’ lab was prepared to answer that question. It had developed a test that could detect folate-blocking antibodies in blood.

Samples from the 28 children showed that 25 of them were carrying these antibodies.

“So we had an explanation why, even though they had normal circulating folate, the brain was not getting folate,” Quadros says.

They also thought they could correct the deficiency with leucovorin, a form of folate that can take “an alternative pathway into the brain,” Quadros says.

When children in the study got leucovorin, folate levels in their brains went up and, in some, their symptoms appeared to decrease.

Studies with caveats

The results with leucovorin, though highly preliminary, percolated through the autism community for more than a decade.

Then in 2018, another small study amplified interest in the drug.

The study involved 48 autistic children with language impairment. It found that those who got leucovorin during the 12-week study period showed greater improvement in communication skills.

The study’s first author was Dr. Richard Frye, a controversial figure in the medical community and a prominent advocate of leucovorin treatment for autistic children.

But even Frye says the drug is far from a cure.

“This isn’t a panacea, this isn’t the autism pill,” he says. “Some kids respond dramatically, but that’s not the norm.”

Most improve slowly over many years, he says, and require a range of therapies in addition to leucovorin.

Frye studied the drug during appointments at the University of Arkansas and then Phoenix Children’s Hospital. He left both institutions after his research was questioned and now practices at a private clinic.

Frye believes that cerebral folate deficiency is present in many children with autism. But confirming the deficiency requires a spinal tap, which can be painful.

As a result, Frye says, he and other researchers typically use a less reliable measure: the presence of folate-blocking antibodies in a child’s blood.

“So we can’t say they have cerebral folate deficiency,” he says, “but we can say, okay there is some kind of block that would put them at risk.”

Another caveat is that leucovorin appears to help many children who do not have folate-blocking antibodies.

To Frye, this simply suggests that leucovorin is working in some other way.

“There’s strong data that this is really a very promising treatment,” Frye says. “Is it enough for changing of the label? That’s up to the FDA.”

Frye is working on a randomized, controlled trial that uses a purified form of leucovorin to treat children with autism. That should offer clearer results, he says.

Been there, done that

In the meantime, the FDA is relying on studies that are badly flawed, says Dr. Shafali Jeste, chair of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“These trials have been conducted without the rigor that we would really want to determine that something should be FDA approved for autism,” she says.

So Jeste doesn’t prescribe leucovorin. And when parents ask her about it, she has a standard response:

“If I had a pill that I could give your child to help them talk, or to completely reverse the core symptoms of autism, I would be the first to be prescribing it,” she says. “We don’t have one.”

At least one segment of the autism community has already tried leucovorin — and found it lacking.

Decades ago, the drug became a popular treatment for children with Fragile X syndrome, an inherited condition that affects a region of the X chromosome and is a leading cause of autism.

Until genetic tests for Fragile X arrived in the 1990s, scientists used a microscope to look for “fragile” or “broken” regions on the X chromosome. And they found that those abnormalities were easier to see in brain cells grown in a medium low in folic acid (a synthetic form of folate).

“So the very first, and most obvious theory was that Fragile X must have something to do with folic acid metabolism,” says Dr. Michael Tranfaglia, medical director of the FRAXA Research Foundation and parent of an adult child who has the disorder and severe autism.

Parents started giving folic acid to their children with Fragile X. When that didn’t work, they moved on to folinic acid — leucovorin.

“There was a lot of excitement about that, until people started doing actual clinical trials,” Tranfaglia says. Then it became clear the drug was no better than a placebo.

Now, Tranfaglia says, leucovorin is back.

“It’s not terribly surprising,” he says, “because for every supplement and every vitamin you can possibly imagine, someone has proposed some kind of link to autism.”

Usually, though, that someone is not running the FDA — the agency that determines whether a drug is safe and effective.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

A once-obscure cancer drug has become a celebrity in the autism community. The drug is called Leucovorin, and it’s been in high demand since the Trump administration endorsed it as a treatment for some children with autism. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports that the drug joins a long list of autism remedies whose popularity has outpaced the science.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: At a press conference in September, federal officials made some big claims about Leucovorin, a prescription drug usually reserved for cancer patients. Here’s Dr. Marty Makary, commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

MARTY MAKARY: We are going to change the label to make it available. Hundreds of thousands of kids, in my opinion, will benefit.

HAMILTON: Months later, the FDA has yet to make good on Makary’s promise. Since his remarks, though, nearly 25,000 people have joined a Facebook group called Leucovorin for Autism, and some doctors have started writing off-label prescriptions. That’s led to a shortage of the drug, which the FDA is trying to fix by allowing imports of a version sold in Canada. It’s all part of a familiar cycle for Dr. Paul Offit of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Offit says he realized years ago that Leucovorin was a dead end.

PAUL OFFIT: I saw it for what it was, which was yet the next magic medicine to treat autism in a long line of magic medicines to treat autism that haven’t worked.

HAMILTON: Offit has chronicled the rise and fall of many of those products in his books and blog posts.

OFFIT: First, it was Secretin, an intestinal hormone. Then it was Lupron, chemical castration, antibiotics, specifically antifungals because you just needed to control yeast in the intestine, mega vitamins, nicotine patches, and then my personal favorite, which is raw camel’s milk.

HAMILTON: Offit expects Leucovorin to find a place on that cautionary list.

OFFIT: I think the FDA has failed here to stand between the public and the pharmaceutical industry to make sure that we get drugs that are tested to be safe and effective, when this clearly hasn’t been well tested to be effective.

HAMILTON: The rationale for Leucovorin’s use in autism rests on its link to a form of vitamin B called folate and to a condition called Cerebral Folate Deficiency. The deficiency affects brain development. Children who have it are prone to seizures, muscle weakness, cognitive impairment and, in some cases, autism. One cause of Cerebral Folate Deficiency is a rare genetic mutation that blocks folate in the bloodstream from reaching the brain. Another cause was proposed about 20 years ago by scientists, including Edward Quadros of Suny-Downstate Medical Center.

EDWARD QUADROS: I’ve been researching folate for almost three decades.

HAMILTON: Quadros suggested that Cerebral Folate Deficiency could also be caused by the body’s own immune system. How? By making an antibody that acted like that rare genetic mutation to prevent folate in the bloodstream from reaching the brain. In 2005, Quadros coauthored a study suggesting a link between this deficiency and autism. The study involved 28 children being treated by a doctor in Germany for a range of developmental disorders. All of these kids had low levels of folate in their cerebrospinal fluid, the liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. But Quadros says the doctor in Germany didn’t know why.

QUADROS: So he contacted us and asked, could this be an autoimmune disorder? Would you look at it?

HAMILTON: Quadros says blood samples from the 28 children showed that 25 of them were carrying antibodies capable of blocking folate.

QUADROS: So we had an explanation why even though they had normal circulating folate, the brain was not getting folate.

HAMILTON: Quadros says his team thought they could correct the deficiency with Leucovorin.

QUADROS: It’s basically a derivative of folate, which can bypass and go through an alternative pathway into the brain.

HAMILTON: When children in the study got Leucovorin, folate levels in their brains went up and some kids even appeared to get better. The results percolated through the autism community for more than a decade. Then in 2018, another small study amplified interest in the drug. It found that among 48 autistic children with language impairment, those who got Leucovorin for 12 weeks showed greater improvement in verbal skill. Dr. Richard Frye was the lead author and remains a prominent advocate for Leucovorin treatment. But even Frye says it’s no cure.

RICHARD FRYE: This isn’t a panacea. This isn’t the autism pill. It definitely can help some kids. Some kids, you know, respond dramatically, but that’s not the norm.

HAMILTON: Most improve slowly over many years, he says, and require a range of therapies in addition to Leucovorin. Frye studied the drug during appointments at the University of Arkansas and then the University of Arizona. He left both institutions after they questioned his research and now practices at a private clinic. Frye believes many children with autism do have Cerebral Folate Deficiency, but confirming the deficiency requires a spinal tap, which can be painful. As a result, Frye says he and other researchers typically use a less reliable measure, the presence of folate-blocking antibodies in a child’s blood.

FRYE: So we can’t say they have Cerebral Folate Deficiency, which is specifically defined as a level below normal. But we can say, OK, there’s some type of block that would put them at risk for having Cerebral Folate Deficiency.

HAMILTON: Another caveat is that Leucovorin appears to help many children who do not even have the folate-blocking antibodies. Frye says this suggests that Leucovorin is working in other ways.

FRYE: There’s strong data that this is really a very promising treatment. Is it enough for changing of the label? That’s up to the FDA.

HAMILTON: Frye says he’s working on a randomized controlled trial of a purified form of Leucovorin that should offer clearer results. In the meantime, the FDA is relying on studies that are badly flawed, says Dr. Shafali Jeste, the chair of pediatrics at the University of California, Los Angeles.

SHAFALI JESTE: These trials have been conducted without the rigor that we would really want to determine that something should be FDA approved for autism more broadly.

HAMILTON: So Jeste doesn’t prescribe Leucovorin. And when parents ask her about it, she has a standard response.

JESTE: If I had a pill that I could give your child to help them talk or to completely reverse the core symptoms of autism, I would be the first to be prescribing it because we would love to have a treatment like that, right? We don’t have one.

HAMILTON: At least one segment of the autism community has already tried Leucovorin and found it lacking. Decades ago, the drug became a popular treatment for children with Fragile X Syndrome, a leading inherited cause of autism. Dr. Michael Tranfaglia is the parent of an adult child with Fragile X and severe autism. Tranfaglia is also the medical director of FRAXA, a foundation that funds research on the genetic condition. He says early on, scientists realized that the chromosomal differences found in Fragile X were visible only in cells deprived of folate.

MICHAEL TRANFAGLIA: So the very first and most obvious theory was that Fragile X must have something to do with folic acid metabolism.

HAMILTON: Parents started giving folic acid to their kids with Fragile X. When that didn’t work, they moved on to folinic acid, or Leucovorin.

TRANFAGLIA: People tried it, and that seemed to work better than the regular folic acid. And there was a lot of excitement about that until people started doing actual clinical trials, and then they realized it was pretty hard to show that it was any more effective than placebo.

HAMILTON: Now Tranfaglia says Leucovorin is back.

TRANFAGLIA: It’s not terribly surprising because for every supplement and every vitamin you can possibly imagine, someone has proposed some kind of link to autism.

HAMILTON: Usually, though, that someone is not running the FDA, the agency that determines whether a drug is safe and effective. Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

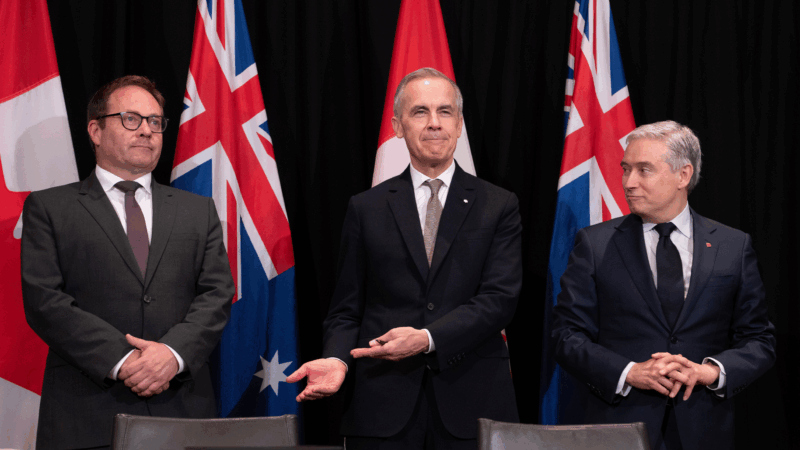

Carney says he backs strikes on Iran ‘with some regret’ as world order frays

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney says he supports the strikes on Iran "with some regret" as they represent an extreme example of a rupturing world order.

Iranian civilians are now fleeing the relentless bombing for neighboring Turkey

As the U.S. military broadens its strikes in Iran, traumatized Iranians are reaching the border with Turkey.

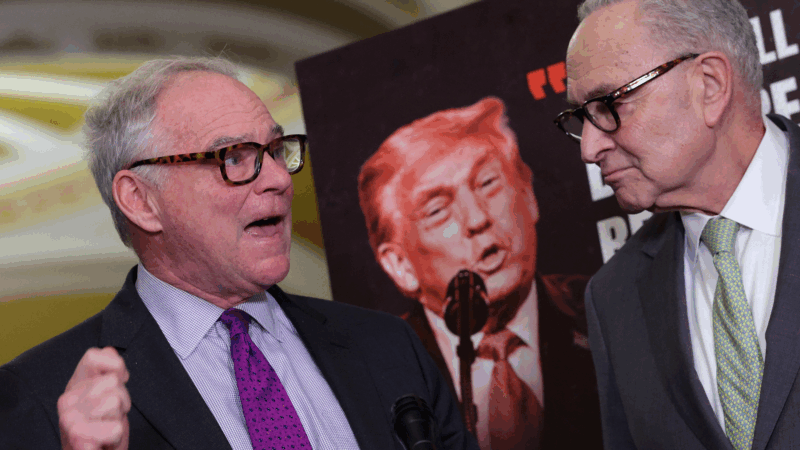

A split Senate votes against measure to constrain Trump’s authorities in Iran

Democrats in the Senate were facing an uphill climb Wednesday in their push to restrain President Trump's ability to wage war against Iran.

WATCH: How traffic dried up in the Strait of Hormuz since the Iran war began

The effective closure of the Strait of Hormuz is "about as wrong as things could go" for global oil markets. Iran achieved it not with a naval blockade, but with cheap drones.

As Mississippi waits to spend opioid settlement funds, children and families suffer

Mississippi will receive more than $400M to fight the opioid epidemic. So far, officials haven't directed it toward programs that support addiction recovery.

Alabama’s new state climatologist takes the reins

The controversial John Christy is retiring as Alabama’s state climatologist. Lee Ellenburg now assumes the role and is already making a few changes, including declaring that climate change is real and caused by humans.