By removing invasive bullfrogs, scientists help Yosemite’s native turtles recover

Sidney Woodruff has spent multiple summers hiking six or seven miles to a remote corner of Yosemite National Park where she has camped out next to ponds and lakes.

“At night,” Woodruff says, “you look out, it’s pitch black, but you have the moon reflecting off the water.”

Soon, however, the dark quiet would be broken by the telltale sound of an American bullfrog. “Once one starts, another one starts, and then it becomes this big deafening chorus of bullfrog calls happening at once,” she says.

And when Woodruff, who’s an ecology PhD candidate at UC Davis, flashed her headlamp over the water, she says a constellation of eyes blinked back at her, reflecting the light.

“The bullfrogs were there by the thousands upon thousands at just one given site,” she recalls.

These frogs, however, were not supposed to be there. Beginning in the late 1800s, they were introduced outside of their native range in eastern North America, often as a food source for people. The result has been a global explosion of the bullfrog — with dire consequences for local wildlife.

But in new research published in the journal Biological Conservation, Woodruff and her colleagues propose a possible — though intensive — countermeasure: a near-total eradication of the bullfrog from habitats that it has invaded. The result was the striking recovery of the Northwestern pond turtle, California’s only native freshwater pond turtle species, at a couple of remote bodies of water within Yosemite National Park.

Giant froggy mouths

The American bullfrog is massive — “maybe the size of a grapefruit in your hand,” says Woodruff. “And they will literally just feed on anything that fits into their mouth.”

That includes salamanders, snakes, frogs, small birds and rodents, and pond turtle hatchlings, which Woodruff and her labmates sometimes refer to as “‘little cookies,’ because they’re so cute.”

The Northwestern pond turtle is a species that has nearly vanished from much of its historic range up and down the West Coast due to habitat loss, climate change, pollution — and of course, the American bullfrog.

The national park previously conducted a massive bullfrog eradication effort in Yosemite Valley — in part to save the pond turtles — but it was too late. The turtles couldn’t stage a comeback.

At the remote bodies of water that Woodruff was studying, though, the situation was different. There were still some older, larger turtles, but no smaller individuals — none that were alive, anyway.

sludge

“The only time that we are coming across young, small turtles is when they are popping up in these bullfrog stomachs,” says Woodruff. “So you have no younger individuals coming up through the ranks.”

Woodruff wanted to know: If the bullfrogs from these backcountry ponds were removed while there were still older turtles present, might the population show signs of recovery?

Resurrecting a food web

To answer that question, Woodruff and her colleagues conducted a combination of night surveys to remove the adults and day surveys to go after bullfrog egg masses. Across two sites, she estimates they removed some 16,000 bullfrogs, amounting to a near-complete eradication.

And after several years of removal, “we came across our first couple of small pond turtle hatchlings and juveniles swimming out in the environment,” says Woodruff. “So once we removed that heavy bullfrog presence, those younger turtles were free from that predation and able to grow up.”

It wasn’t just the pond turtles. The researchers also spotted certain types of snakes and newts making a comeback.

“You see what the food web looks like and how it should look like,” says Woodruff. “All of these native species that have evolved with each other to kind of keep each other in check, with no one species really dominating out.”

Woodruff says the study offers a potential tool for reversing the decline of certain species and restoring freshwater ecosystems — under certain circumstances. “This isn’t something that will be a one size fits all solution,” she allows.

“This work is really important in that it documents the success of invasive species removal efforts, which can be difficult and time-consuming,” says Caren Goldberg, a research geneticist with the US Geological Survey who didn’t contribute to the research. “Turtles live a long time, and populations can appear to be persisting without any juveniles surviving, so understanding how to increase juvenile survival is important work.”

Kaili Gregory, a PhD student in wildlife conservation at the University of Georgia who wasn’t involved in the study, agrees that the results are encouraging. “But,” she adds, “this Northwestern pond turtle goes from central California up to Washington. That’s a lot of area to remove bullfrogs.”

And Gregory says keeping bullfrogs from reinvading an area requires near constant vigilance, which means wildlife managers will have to be strategic.

“Maybe parts of the population are really important for genetic diversity,” Gregory says. “Or it’s high-quality habitat, maybe that’s where we really focus our efforts.”

Meanwhile, in Yosemite, there’s been a partial return to an earlier soundscape.

“As the bullfrog population went down,” says Woodruff, “you started to hear some of our native chorus frogs again. They’re the ones that have this iconic Hollywood ribbit sound.”

In other words, once the bullfrogs croak, the native frogs can finally croon.

Transcript:

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

American bullfrogs, which were once confined to much of eastern North America, have exploded around the world with dire consequences for native species. Now researchers say they may have found a way to help that affected wildlife rebound. Here’s NPR’s Ari Daniel.

ARI DANIEL, BYLINE: Sidney Woodruff has spent multiple summers hiking to a remote corner of Yosemite National Park, where she’s camped out next to ponds and lakes.

SIDNEY WOODRUFF: At night, you have, you know, the moon reflecting off the water.

DANIEL: Inevitably, the dark quiet is broken by an American bullfrog.

WOODRUFF: Like, (imitating American bullfrog) kind of noise that they do. Once one starts, another one starts, and then it becomes this, like, big, deafening chorus.

DANIEL: Woodruff, who’s an ecology Ph.D. candidate at UC Davis, remembers flashing her headlamp over the water and seeing a constellation of eyes blinking back at her, reflecting the light.

WOODRUFF: The bullfrogs were there by the thousands upon thousands.

DANIEL: But these frogs were not supposed to be there. For decades, people introduced them outside their native range, including in Yosemite, where the amphibians mounted an invasion of swaths of the park. And these frogs, they’re massive.

WOODRUFF: Maybe the size of a grapefruit in your hand, and they will literally just feed on anything that fits into their mouth.

DANIEL: Like salamanders, snakes, frogs, small birds and rodents and…

WOODRUFF: Pond turtle hatchlings – we sometimes refer to them as little cookies because they’re so cute.

DANIEL: The northwestern pond turtle is California’s only native freshwater turtle, a species that’s nearly vanished from the West Coast due to several reasons, one of them being the American bullfrog. The national park previously conducted a massive bullfrog eradication effort in Yosemite Valley, in part for the pond turtles, but it was too late. The turtles couldn’t stage a comeback. At the remote bodies of water that Woodruff was studying, though, the situation was different. There were still some older, larger turtles and…

WOODRUFF: The only time that we are coming across young, small turtles is when they are popping up in these bullfrog stomachs. So you have no younger individuals coming up through the ranks.

DANIEL: Woodruff wanted to know if the bullfrogs from these backcountry ponds were removed while there were still older turtles present, might the population show signs of recovery? So she and her colleagues did a combo of night surveys to remove the adults and day surveys…

WOODRUFF: To go after those bullfrog egg masses.

DANIEL: Across two sites, Woodruff estimates they removed some 16,000 bullfrogs – a near complete eradication. And after multiple years…

WOODRUFF: We came across our first couple of small pond turtle hatchlings and juveniles swimming out in the environment. So once we removed that heavy bullfrog presence, those younger turtles were free from that predation and able to grow up.

DANIEL: The researchers also spotted certain snakes and newts making a comeback.

WOODRUFF: You see what the food web looks like and how it should look like – right? – with no one species really dominating.

DANIEL: Woodruff says the study offers a potential tool for restoring freshwater ecosystems under certain circumstances. The results are published in the journal Biological Conservation. Kaili Gregory is a Ph.D. student in wildlife conservation at the University of Georgia who wasn’t involved in the research.

KAILI GREGORY: It was encouraging to see that it’s effective, but this northwestern pond turtle goes from central California up to Washington. That’s a lot of area to remove bullfrogs.

DANIEL: And she says keeping bullfrogs out requires near constant vigilance, so wildlife managers will have to be strategic.

GREGORY: Maybe it’s parts of the population that are really important for genetic diversity, or it’s high-quality habitat. Maybe that’s where we really focus our efforts.

DANIEL: Meanwhile, in Yosemite, Sidney Woodruff says there’s been a partial return to an earlier soundscape.

WOODRUFF: As the bullfrog population went down, you started to hear some of our native chorus frogs again.

DANIEL: In other words, once the bullfrogs croak, the native frogs can finally croon.

Ari Daniel, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

‘Scarpetta’ is a captivating murder mystery — and a high-wire balancing act

Based on a series of novels by best-selling author Patricia Cornwell, Scarpetta follows two different mysteries from two different timelines. It's structurally complicated — but it all holds up.

‘Derry Girls’ creator returns with a gleeful riff on the murder mystery

In the hilarious Netflix series How to Get to Heaven from Belfast, three women learn that a long estranged school friend has died in a suspicious manner — and take it upon themselves to investigate.

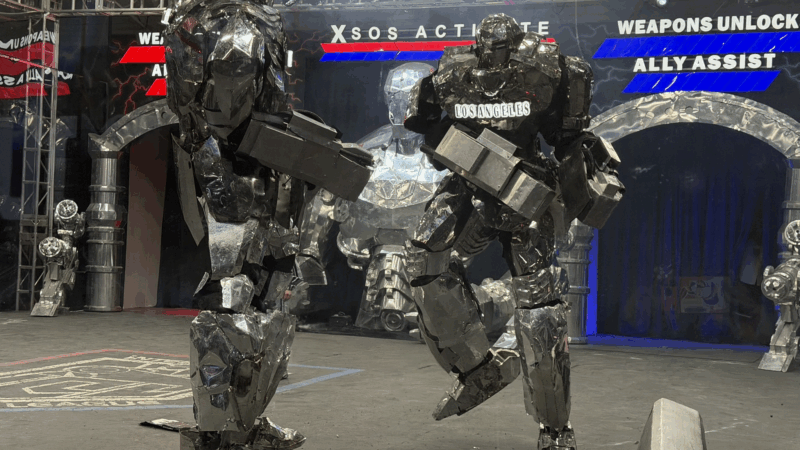

Giant robots battle it out in Detroit’s Robowar

Fighting robots is a cultural fantasy going back at least to Richard Matheson's 1956 story "Steel." One Detroit impresario is now bringing the idea to the stage — and real audiences.

Bill would move Alabama to closed primaries

Right now, any Alabama voter can participate in a primary election. Lawmakers in Montgomery took up a bill this week that would change that system.

Why ‘Sinners’ should win best picture (but probably won’t) — and more Oscar predictions

NPR critics share their hopes and predictions for the 2026 Academy Awards, which air on Sunday.

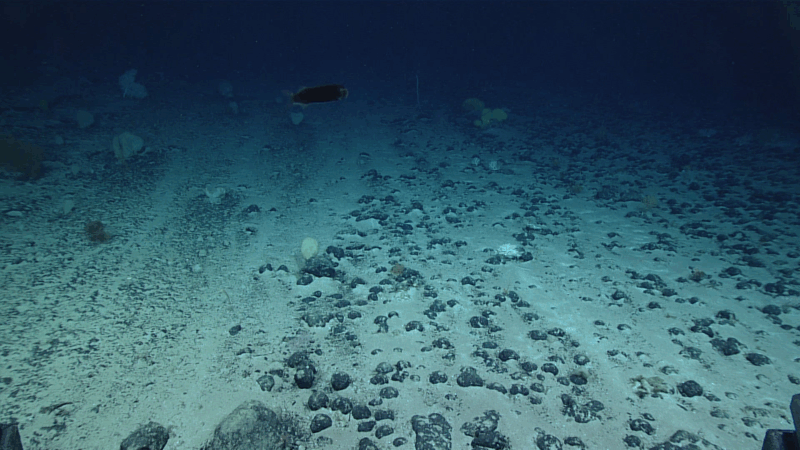

Countries are negotiating rules to mine the deep sea. The U.S. is pushing ahead alone

With growing interest in mining critical metals from the seafloor, countries are now negotiating international rules. The Trump administration is forging ahead on its own, speeding up environmental review for mining the fragile ecosystem.