By land and by sea, these new nonfiction books will carry you away

I like the country, but I wouldn’t want to live there. My husband and I are of one mind about that. Years ago, when we were house hunting, we opened the kitchen door of a little city rowhouse and surveyed, not a grassy backyard, but a concrete slab that formed a grim little patio. “No mowing!” my husband cried ecstatically. We bid on that house — still our home — the very next day.

Clearly, I’m not the target audience for Helen Whybrow’s memoir, The Salt Stones; yet, I was transported by it. Whybrow, a former editor, has lived for over 20 years with her family on Knoll Farm in Vermont. There, she tends a flock of some 90 Icelandic sheep, known for their double-ply coats and disinclination to docility.

Whybrow’s closely-observed accounts of her working life as a shepherd are filled with muck, sweat and a hard-won sense of the interconnectedness of the natural world. Here are snippets from an extended passage where Whybrow — along with her then 3-year-old daughter, Wren — release the sheep from their paddock to munch their way through a spring meadow. Even as she leads her sheep, Whybrow leads her readers into a deeper recognition of how the sublime and the sinister grow side-by-side:

Our pant legs are drenched and heavy with dew. The sheep stream ahead of us, calling to each other in the yellow buttercups . … We walk after them, as if through a light-filled doorway in a dream. …

Nearby, I show [Wren] the diminutive plant called shepherd’s purse, with its tiny white flowers . … helpful for diarrhea. Next to it I spot one of those tiny thin-skinned snails, inside which is an invisible worm that can find its way into the brain of a sheep and drive it mad.

Lobo, the farm’s guard llama who protects the flock against predators like coyotes, will later be felled by one of those worms carried in those “tiny, gleaming golden snails in the grass, deliverers of death.”

Reading about Whybrow’s life has made me more aware of the teeming environment — above and below that backyard concrete slab — that I normally don’t notice.

A Marriage at Sea, by Sophie Elmhirst, is a true story that’s part extreme adventure tale, part meditation on the mystery of a loving partnership.

Maurice and Maralyn Bailey were a lower-middle-class English couple bored with their lives in the early 1970s. Maralyn, the go-getter of the two, decided they should sell their suburban bungalow, buy a boat, and sail ’round the world.

In June 1972, the couple set off on a 31-foot wooden sloop called The Auralyn. A year later, in the middle of the Pacific, a whale breached out of the briny deep and knocked a hole in the Auralyn. It sank within minutes.

Maralyn (who couldn’t swim) and Maurice spent four months adrift on a rubber raft. They survived, barely, by catching and eating raw fish and birds, sucking water out of turtles’ eyeballs, and, in depressive Maurice’s case, fighting the temptation to tip himself overboard.

Elmhirst, who writes for The Guardian and The New Yorker, knows how to tell a perfect storm of a story, relying, in part, on Maralyn’s diary. Here, for instance is the day when the pair “woke to find themselves sunk in a hollow in the middle of the raft.” The bottom of the rubber raft had been pierced by the spines of tiny fish and needed patching. Afterwards, to stay afloat, the couple “had to pump two or three times an hour.” Elmhirst then uses poetic license to enter into Maurice’s thoughts:

Now and then, in brighter moments, Maurice liked to entertain the idea that they had become at one with the Pacific. … But times like this exposed the absurdity of such a view. … Boats, like humans are in a state of permanent decline. Every time a boat touches the water, it degrades. … They were not meant to be here.

I’m only skimming the surface of the existential depths of A Marriage at Sea. This is a tale that makes you understand the lure of the open water and why it’s best, perhaps, that most of us resist it.

In Vermont, small town meetings grapple with debate on big issues

Typically concerned with local issues, residents at town meetings in Vermont and elsewhere increasingly use the forum to debate polarizing national and international events.

Alabama man, on death row since 1990, to get new trial

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday declined to review the summer ruling from the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The decision paves the way for Michael Sockwell to receive a new trial.

Supreme Court blocks redrawing of New York congressional map, dealing a win for GOP

At issue is the mid-term redrawing of New York's 11th congressional district, including Staten Island and a small part of Brooklyn.

U.S. states take steps to guard against any potential threat from Iran

Iran has made prior attempts to launch terrorist attacks on U.S. soil, but all have been thwarted in recent years. States are bracing for a heightened threat after the war.

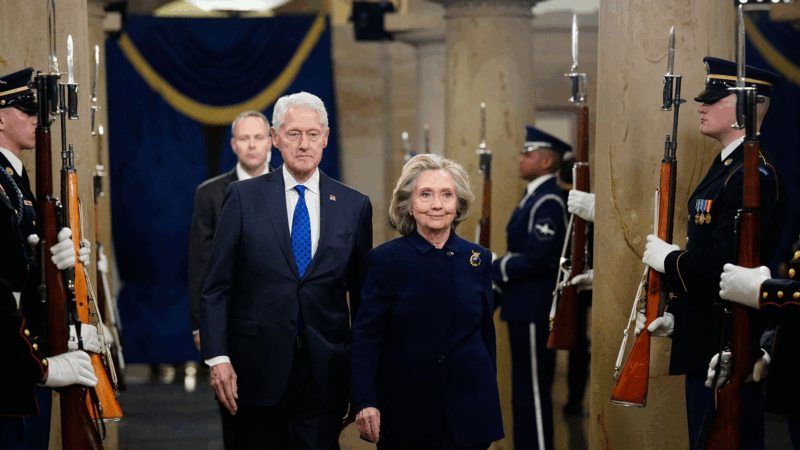

Video of Clinton depositions in Epstein investigation released by House Republicans

Over hours of testimony, the Clintons both denied knowledge of Epstein's crimes prior to his pleading guilty in 2008 to state charges in Florida for soliciting prostitution from an underage girl.

Some Middle East flights resume, but thousands of travelers are still stranded by war

Limited flights out of the Middle East resumed on Monday. But hundreds of thousands of travelers are still stranded in the region after attacks on Iran by the U.S. and Israel.