Black bear populations are bouncing back. Here’s how these Texas towns are coping

ALPINE, Texas — In one of the most remote corners of Texas, Matt Hewitt is unlocking the door to a giant steel trap he’s hoping will catch a black bear.

“It’s completely empty,” Hewitt says, as he reaches for a bucket with bait – days-old glazed donuts and frozen cantaloupe.

Hewitt, a researcher at the Borderlands Research Institute, affiliated with Sul Ross State University, leads a group that captures and collars black bears to try and get an idea of just how many are roaming the mountains and desert stretches of Far West Texas. And although it’s too soon to say exactly how many bears there are, Hewitt believes “there’s more than people realize.”

Historically, black bears were once the biggest predator to travel the region in large numbers, but overhunting and habitat loss led to their decline over several decades.

But in recent years, the number of black bears in West Texas have been on the rise: sightings in the state have jumped from nearly 80 in 2020 to at least 130 so far this year, according to state data. And in other states, researchers believe black bear populations are growing too.

But in West Texas, for all the celebration of the bears’ return to the wilderness, there are challenges and concerns as bears have ventured into neighborhoods, gotten into yards and posed a threat to livestock and pets.

“I don’t mind the bears coming back, we don’t want them wiped out, that’s for sure,” said Pam Clouse, who lives in Alpine, an area that’s seen a number of bear encounters in recent years. “You know, they were almost extinct.”

Clouse and her husband, Ken, both grew up in West Texas, and consider themselves wildlife enthusiasts. During drought years, the couple would sprinkle buckets full of corn on their yard and keep troughs of water on their property for wandering wildlife like deer and javelina.

Recently, they removed the food and water at the suggestion of state officials, and have even electrified their fence, too — all in effort of keeping the bears away.

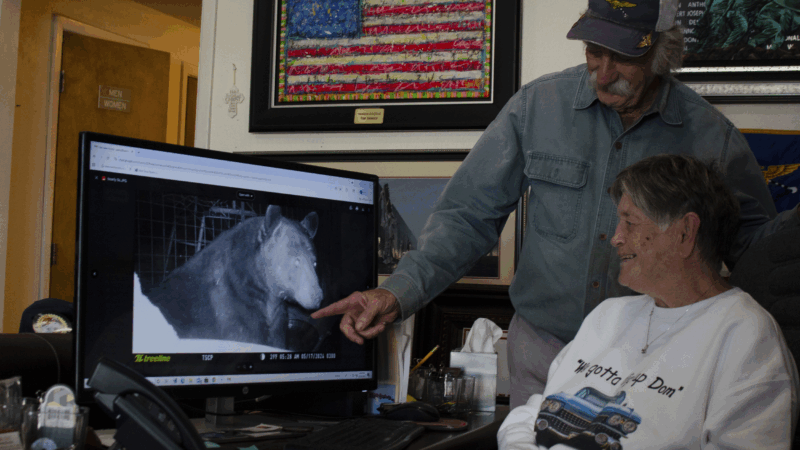

But the bears are still coming, they say. “These bears are pretty large,” said Pam Clouse, as she pulled up an image of a bear from a trail camera at their house. “They’re probably about 4, 500 pounds if I had to guess.”

The Clouses feel like more can be done to ease residents’ concerns over bears wandering onto their property. “I’m not promoting a hunting season for the black bears,” said Ken Clouse. “But there’s got to be some type of control.”

Learning to live with bears

In states like Montana and Colorado, residents have adapted to living with bears by installing bear-resistant dumpsters and trash bins and, in some cases, installing alarm systems or sprinklers — things to try and startle bears.

But of all the measures, wildlife biologists stress removing food and anything that might attract a hungry bear.

During the late summer and fall months, as black bears prepare to den, they’re looking to eat as much as possible, and they’ll go through great lengths to consume the 20,000 daily calories they’re after.

“They have a great sense of smell, much better than our own,” said Raymond Skiles, former wildlife biologist at Big Bend National Park in West Texas. “So, number one, they can smell food when you and I would never have a clue.”

Skiles was at Big Bend National Park when black bears made their return there in the late 1980s. He said it took time and work at the park, but they were able to adapt to the return of bears there. The park brought in dumpsters that were hard for bears to get into, educated visitors about the animal, and put into place rules that ensured food wasn’t being left out.

Today, Skiles said, those measures have gone a long way in reducing the possibility of bear-human conflict in the Chisos Mountains, one of the most popular corners of the park. Now, Skiles wonders if the same can happen in cities and towns across West Texas.

From the national park, an expansive stretch of desert land roughly the size of Rhode Island, the bears are now pushing north. Wildlife conservationists here say it’s likely because the land has reached what they call “carrying capacity.”

“And when you’re over carrying capacity, there’s not [enough] resources on the natural landscape for those animals,” explained Krysta Demere, a wildlife biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “So, then they begin to move out and search for new food sources.”

Part of Demere’s job is to help people across West Texas get ready to live with bears, something they haven’t experienced in well over 80 years.

“And that’s a long time,” said Demere. “That means there’s not a generation alive today that’s had to live with [the] black bear before.”

But the next generation in Alpine and the ones after that will likely grow up knowing this place, once again, as bear country.

HUD proposes time limits and work requirements for rental aid

The rule would allow housing agencies and landlords to impose such requirements "to encourage self-sufficiency." Critics say most who can work already do, but their wages are low.

Paramount and Warner Bros’ deal is about merging studios, and a whole lot more

The nearly $111 billion marriage would unite Paramount and Warner film studios, streamers and television properties — including CNN — under the control of the wealthy Ellison family.

A new film follows Paul McCartney’s 2nd act after The Beatles’ breakup

While previous documentaries captured the frenzy of Beatlemania, Man on the Run focuses on McCartney in the years between the band's breakup and John Lennon's death.

An aspiring dancer. A wealthy benefactor. And ‘Dreams’ turned to nightmare

A new psychological drama from Mexican filmmaker Michel Franco centers on the torrid affair between a wealthy San Francisco philanthropist and an undocumented immigrant who aspires to be a dancer.

Bill making the Public Service Commission an appointed board is dead for the session

Usually when discussing legislative action, the focus is on what's moving forward. But plenty of bills in a legislature stall or even die. Leaders in the Alabama legislature say a bill involving the Public Service Commission is dead for the session. We get details on that from Todd Stacy, host of Capitol Journal on Alabama Public Television.

My doctor keeps focusing on my weight. What other health metrics matter more?

Our Real Talk with a Doc columnist explains how to push back if your doctor's obsessed with weight loss. And what other health metrics matter more instead.