An ape, a tea party — and the ability to imagine

The ability to imagine things that aren’t real — to make believe — is a fundamental part of being human.

What starts as imaginary friends and playing pretend develops into an ability, over time, to step out of reality. To daydream and plan a summer vacation. To invent a new recipe. To put oneself in another’s shoes.

It’s long been thought that this ability to imagine is unique to humans.

But now, a series of sterile tea parties with a remarkable ape named Kanzi suggests some of our closest ancestors may have the ability too.

“It tells us, for one, that the roots of our imagination were present in the common ancestors that we share with [great apes], which lived 6 to 9 million years ago,” says Chris Krupenye, a cognitive scientist at Johns Hopkins University. “It also tells us there’s much more interesting mental life out there in the world than we previously thought.”

Krupenye is co-author of a new study, published in the journal Science, that aimed to test — for the first time in a controlled experiment — whether apes have the cognitive ability to play pretend.

The subject of the study was Kanzi, arguably the world’s most famous bonobo — an endangered species of ape that’s a smaller cousin to chimpanzees. Raised in captivity, Kanzi had an amazing ability to communicate with humans using symbols and a broad understanding of the English language. (He died last year at the age of 44.)

When asked questions, Kanzi could answer.

“And one of the ways he could respond is through pointing — and that’s not a common behavior for apes,” Krupenye says. “They don’t typically point in the way that humans do.”

That ability allowed Krupenye and his co-author, Amalia Bastos, a cognitive scientist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, to ask Kanzi questions like they would a human child.

So to test whether he had the cognitive ability to imagine, they modeled their experiments off a series of developmental psychology studies that were conducted with children in the 1980s. Those studies used a pretend tea party to see if kids could track an imaginary object, like a cup of pretend juice.

“With Kanzi, we were able to do more or less the exact same thing,” Krupenye says.

At Kanzi’s home, the Ape Initiative in Des Moines, Iowa, Krupenye and Bastos set up a series of recorded tea parties.

In one of the experiments, the researchers would set two empty, transparent cups on a table between them. They’d then take an empty, transparent pitcher and pretend to pour juice in both. They’d then pick up one cup and pretend to pour the nonexistent juice back in the pitcher.

“At that point, there’s only one bit of imaginary juice left in the remaining cup,” Krupenye says. “So [we’d] push the table forward and ask Kanzi: Where’s the juice?”

Roughly 70% of the time, Kanzi pointed at the correct place.

For decades, scientists have observed apes doing things in the wild and in captivity that look like pretend play. Young female chimpanzees have been seen carrying around a stick or log and treating it like a baby or doll. But it’s difficult to know if that’s what they’re pretending.

The new study shows that apes — or at least one, in Kanzi — could do more than just play pretend, says Kristin Andrews, a professor of philosophy at City University of New York, who was not involved in the study.

“[Kanzi’s showing] pretense and imagination, which takes it to another step,” says Andrews, who focuses on animal cognition and minds.

Pretense and imagination is the ability to hold in mind a version of the world that isn’t real, while pretending that it is. Andrews says it’s a valuable cognitive skill, in part because it allows an individual to play out different scenarios in their head before making a decision.

“It helps them make choices,” she says.

Whether bonobos and chimpanzees are actively doing this in the wild is difficult to say, she says, “But what I think the study with Kanzi tells us is that great apes have the capacity to hold these alternative representations” in their mind. And it’s possible, she adds, other animals can too.

Transcript:

AILSA CHANG, HOST:

The ability to imagine things that aren’t real is a fundamental part of the human experience. Scientists have long suspected some animals also have the ability to imagine and play pretend. NPR’s Nate Rott reports on a new study that shows at least one can.

NATE ROTT, BYLINE: It’s important to note before we really get into it that the subject of this new study is a pretty remarkable ape. This isn’t his first time on NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MONTAGE)

ADAM COLE, BYLINE: Kanzi is a bonobo, a smaller cousin of the chimpanzee. He doesn’t use hand…

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: Kanzi – he’s the world’s most famous bonobo and a bit of a show off. But Kanzi’s little sister…

ROTT: Kanzi was raised in captivity and lived that way the rest of his life. He died last year at the age of 44. But what got him full-page pictures in Time magazine and National Geographic, with an accompanying video segment for the latter, was his ability to communicate with humans using symbols and his comprehension of the English language.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED CARETAKER: Look right at the camera. Good boy. You’re doing so good. Just a couple more.

JOEL SARTORE: I realize as they talk to Kanzi, he understands almost everything they say.

ROTT: A study published in 1993 found that when Kanzi was 8 years old, he could outperform a 2-year-old human when given more than 600 spoken instructions.

CHRIS KRUPENYE: We don’t know exactly what he grasped, but you could ask him a question and often he would respond in the way that he should.

ROTT: Chris Krupenye is a cognitive scientist at Johns Hopkins University and a coauthor of the new study. He worked with Kanzi before he died.

KRUPENYE: And one of the ways he could respond is through pointing, and that’s not a common behavior for apes. They don’t typically point in the way that humans do.

ROTT: Krupenye says this ability to point allowed researchers to more or less ask Kanzi questions like they would a human child. And the question Krupenye wanted to answer is whether animals also have the cognitive ability to make believe.

KRUPENYE: Kids will have tea parties with their dolls. They might have an imaginary friend. They might play house with their friends. So they’re showing these roots of imagination within the first years.

ROTT: And there’s been observations of apes in the wild and in captivity doing similar things.

KRUPENYE: Young female chimpanzees have been observed carrying around sticks or logs in ways that look like they’re treating them like a doll or a baby.

ROTT: What’s less clear is whether they’re actually playing pretend, which is why Krupenye set up a series of controlled experiments with Kanzi to test, for the first time, whether one of humanity’s closest relatives can track an imaginary object by running an experiment very similar to what psychologists have done to test imagination in kids.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

UNIDENTIFIED RESEARCHER: All right. So let’s play a game. Let’s find the juice, OK?

(SOUNDBITE OF CUP CLATTERING)

ROTT: Think of it like a really sterile tea party – Kanzi on one side of the table, a human partner, a researcher, on the other.

KRUPENYE: And on the table, the partner would put two empty, transparent cups.

ROTT: Before pretending to pour juice into them from an empty, transparent pitcher. They’d then pretend to pour the imaginary juice from one of the cups back into the pitcher.

KRUPENYE: And at that point, there’s only one bit of imaginary juice left in the remaining cup, and the partner pushed the table forward and asked Kanzi, where’s the juice?

ROTT: And roughly 70% of the time, Kanzi would pick the right one. Now, Krupenye says this is an experiment of one individual and a pretty unique one at that. So more research is needed to make a broad generalization about whether all bonobos or other apes can do this. But the fundamental question of whether only humans can imagine…

KRUPENYE: For that question, all you need is one clear demonstration to say, no, it’s not unique to humans.

ROTT: And he thinks this new study published in the journal Science is that. Nate Rott, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

FBI release photos and video of potential suspect in Guthrie disappearance

An armed, masked subject was caught on Nancy Guthrie's front doorbell camera one the morning she disappeared.

Judge rules 7-foot center Charles Bediako is no longer eligible to play for Alabama

Bediako was playing under a temporary restraining order that allowed the former NBA G League player to join Alabama in the middle of the season despite questions regarding his collegiate eligibility.

American Ben Ogden wins silver, breaking 50 year medal drought for U.S. men’s cross-country skiing

Ben Ogden of Vermont skied powerfully, finishing just behind Johannes Hoesflot Klaebo of Norway. It was the first Olympic medal for a U.S. men's cross-country skier since 1976.

How much power does the Fed chair really have?

On paper, the Fed chair is just one vote among many. In practice, the job carries far more influence. We analyze what gives the Fed chair power.

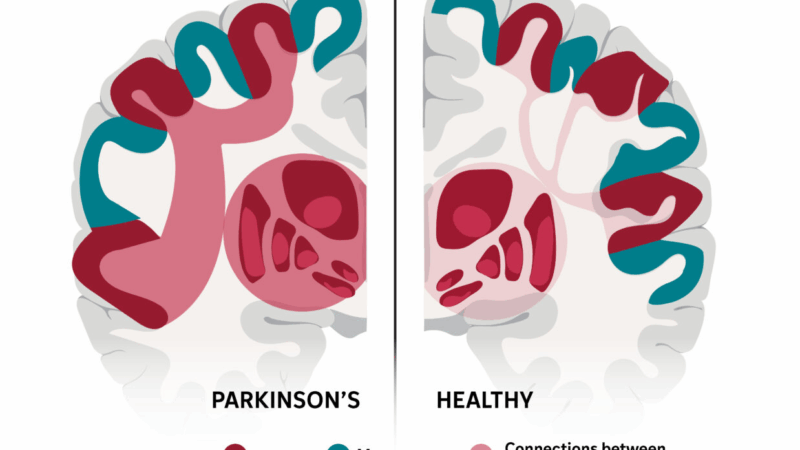

This complex brain network may explain many of Parkinson’s stranger symptoms

Parkinson's disease appears to disrupt a brain network involved in everything from movement to memory.

‘Please inform your friends’: The quest to make weather warnings universal

People in poor countries often get little or no warning about floods, storms and other deadly weather. Local efforts are changing that, and saving lives.