Amputees often feel disconnected from their bionic hands. AI could bridge the gap

Researchers have built a prosthetic hand that, with the help of artificial intelligence, can act a lot more like a natural one.

The key is to have the hand recognize when the user wants to do something, then share control of the motions needed to complete the task.

The approach, which combined AI with special sensors, helped four people missing a hand simulate drinking from a cup, says Marshall Trout, a researcher at the University of Utah and the study’s lead author.

When the sensors and AI were helping, the participants could “very reliably” grasp a cup and pretend to take a sip, Trout says. But without this shared control of the bionic hand, he says, they “crushed it or dropped it every single time.”

The success, described in the journal Nature Communications, is notable because “the ability to exert grasp force is one of the things we really struggle with in prosthetics right now,” says John Downey, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the research.

Problems like that cause many amputees to grow frustrated with their bionic hands and stop using them, he says.

A helping hand

The latest bionic hands have motors that allow them to swivel, move individual fingers, and manipulate objects. They can also detect electrical signals coming from the muscles that are used to control those actions.

But as bionic hands have become more capable, they have also become more difficult for users to control, Trout says.

“The person has to sit there and really focus on what they’re doing,” he says, “which is really not how an intact hand behaves.”

A natural hand, for example, requires very little cognitive effort to carry out routine tasks like reaching for an object or tying a shoelace. That’s because once a person puts the task in motion, most of the work is done by specialized circuits in the brain and spine that take over.

These circuits allow many tasks to be accomplished efficiently and automatically. Our conscious mind only intervenes if, say, a shoelace breaks, or an object is moved unexpectedly.

So Trout and a team of scientists set out to make a smart prosthetic that would act more like a person’s own hand.

“I just know where my coffee cup is, and my hand will just naturally squeeze and make contact with it,” he says. “That’s what we wanted to recreate with this system.”

The team turned to AI to take on some of these subconscious functions. This meant detecting not just the signal coming from a muscle, but the intention behind it.

For example, the AI control system learned to detect the tiniest twitch in a muscle that flexes the hand.

“That’s when the machine controller kicks on, saying, ‘Oh, I’m trying to grasp something, I’m not just sitting still,'” Trout says.

To make the approach work, the scientists modified a bionic hand by adding proximity and pressure sensors. That allows the AI system to gauge the distance to an object and assess its shape.

Meanwhile, the pressure sensors on the fingertips tell the user how firmly their prosthetic hand is holding the object.

Sharing control

The idea of sharing control of a bionic hand addresses a reaction many people have when they use a prosthetic with superhuman abilities, says Jacob George, a professor at the University of Utah and director of the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab.

“You can make a robotic hand that can do tasks better than a human user,” he says. “But when you actually give that to someone, they don’t like it.”

That’s because the device feels foreign and out of their control, he says.

John Downey says that one reason we feel connected to our own hands is that they are controlled jointly by our thoughts and by reflexes in the brain stem and spinal cord.

That means the thinking part of our brain doesn’t have to worry about the details of every motion.

“All of our motor control involves reflexes that are subconscious,” Downey says, “so providing robotic imitations of those reflex loops is going to be important.”

George says the smart bionic hand solves for that issue.

“The machine is doing something and the human is doing something, and we’re combining those two together,” he says.

That’s a critical step toward creating prosthetic limbs that feel like an extension of the person’s own body.

“Ultimately, when you create an embodied robotic hand, it becomes a part of that user’s experience, it becomes a part of themselves and not just a tool,” George says.

Even the most advanced bionic hands still need some help from a human brain, Downey says.

For example, a person can use the same natural hand to gently thread a needle, then firmly lift up a child.

“The dynamic range on that is far beyond what robots typically handle,” Downey says.

That is likely to change, as bionic limbs become increasingly versatile and capable. What won’t change, scientists say, is humans’ desire to retain a sense of control over their artificial appendages.

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

Scientists are using artificial intelligence to help bionic limbs act more like natural ones. NPR’s Jon Hamilton reports on an experimental hand that shares control with the user to carry out tricky tasks like holding up a Styrofoam coffee cup.

JON HAMILTON, BYLINE: The latest bionic hands can swivel, move individual fingers and manipulate objects. They can also detect electrical signals coming from the muscles that used to control those actions. But Marshall Trout, a researcher at the University of Utah, says most prosthetic hands still aren’t very smart.

MARSHALL TROUT: The person has to sit there and really focus on what they’re doing. They have to maintain, like, line of sight with whatever it is they’re trying to handle, which is really not at all how a intact hand behaves.

HAMILTON: Which is one reason that many people who get a fancy prosthetic hand stop using it. So Trout and a team of scientists set out to make a smarter prosthetic that would act more like a person’s own hand.

TROUT: I just know where my coffee cup is and I can reach without having to pay too much attention. And as my hand gets closer, I can kind of feel where it is, and my hand will just naturally squeeze and make contact with it. And that’s kind of what we wanted to try to recreate with the system.

HAMILTON: The team turned to artificial intelligence to take on some of these subconscious functions. This meant detecting not just the signal coming from a muscle, but the intention behind it. For example, Trout says, the AI control system learned to detect the tiniest twitch in a muscle that flexes the hand.

TROUT: The moment we detect that small amount of flexion, that’s when the machine controller kicks on, saying, oh, I’m trying to grasp something. I’m not just sitting still.

HAMILTON: To make the approach work, the scientists modified a bionic hand by adding sensors that see and feel, that allowed the AI system to gauge the distance to an object and assess its shape. Meanwhile, pressure sensors on the fingertips told the user how firmly their prosthetic hand was holding the object. To test the system, Trout’s team asked four people missing a natural hand to use the bionic version to drink from a cup with and without help from AI.

TROUT: With machine assistance, they could very reliably pick up these cups and mime drinking a sip of water out of the cup. And then without the machine assistance, the person just crushed it or dropped it every single time.

HAMILTON: The results appear in the journal Nature Communications. And Jacob George, who oversaw the research at the Utah NeuroRobotics Lab, says they address a problem that people often encounter when they use superhuman technology.

JACOB GEORGE: You can make a robotic hand that can do tasks better than a human user. But when you actually give that to someone, they don’t like it. You know, they actually hate this.

HAMILTON: Because they feel like it’s not a part of them and it’s out of their control. George says this artificial intelligence system shares control with the user.

GEORGE: The machine is doing something and the human is doing something, and we’re combining those two together.

HAMILTON: George says that’s a critical step toward prosthetic limbs that feel like an extension of the person’s own body.

GEORGE: Ultimately, when you create an embodied robotic hand, it becomes a part of that user’s experience. It becomes a part of themselves and not just a tool.

HAMILTON: One reason we feel that way about our own hands is that they’re controlled in part by reflexes in the brain stem and spinal cord. John Downey of the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study, says that means the thinking part of our brain doesn’t have to worry about the details of every motion.

JOHN DOWNEY: All of our motor control involves reflexes that are subconscious. And so providing robotic imitations of those reflex loops is going to be important.

HAMILTON: But Downey says sometimes a human brain is needed to do things artificial intelligence still can’t.

DOWNEY: We can very finely manipulate things like putting a thread through needle and things like that, which take almost no force at all, all the way up to, you know, grabbing a child and lifting them. The dynamic range on that is far beyond what robots typically handle.

HAMILTON: For now, anyway.

Jon Hamilton, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

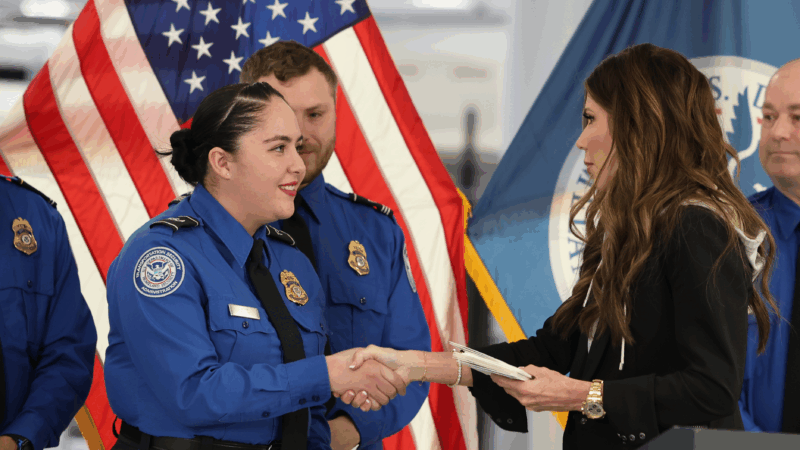

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

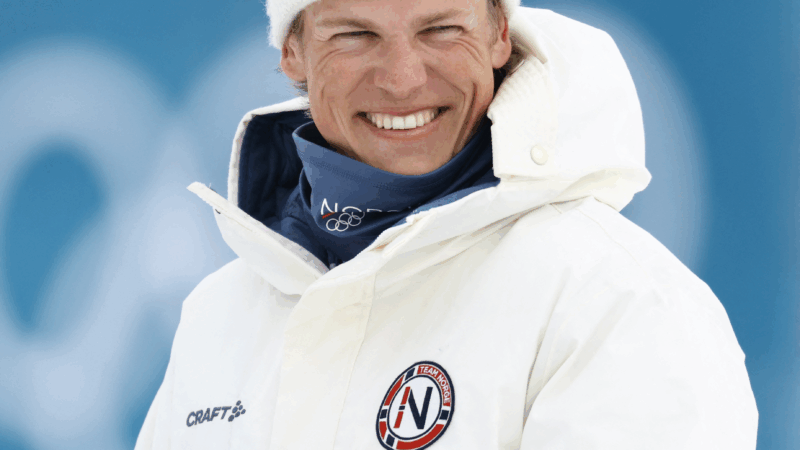

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.