AI’s getting better at faking crowds. Here’s why that’s cause for concern

A Will Smith concert video tore through the internet recently — not for his performance, but for the crowd. Eagle-eyed viewers noticed odd fingers and faces, in the audience, among other visual glitches, and suspected AI manipulation.

Crowd scenes present a particular technological challenge for AI image creation tools – especially video. (Smith’s team hasn’t publicly commented on – or responded to a request from NPR about – how the video was made.) “You’re managing so many intricate details,” said San Francisco-based visual artist and researcher kyt janae, an expert on AI image creation. “You have each individual human being in the crowd. They’re all moving independently and have unique features – their hair, their face, their hat, their phone, their shirt.”

But the latest AI video generation models such as Google’s Veo 3 and OpenAI’s Sora 2 are getting pretty good. “We’re moving into a world where in a generous time estimate of a year, the lines of reality are going to get really blurry,” janae said. “And verifying what is real and what isn’t real is going to almost have to become like a practice.”

Why crowd images matter

This observation could potentially have serious consequences in a society where images of big, engaged crowds at public events like rock concerts, protests and political rallies have major currency. “We want a visual metric, a way to determine whether somebody is succeeding or not,” said Thomas Smith, CEO of Gado Images, a company that uses AI to help manage visual archives. “And crowd size is often a good indicator of that.”

A report from the global consulting firm Capgemini shows nearly three-quarters of images shared on social media in 2023 were generated using AI. With the technology becoming increasingly adept at creating convincing crowd scenes, manipulating visuals has never been easier. With this comes both a creative opportunity – and a societal hazard. “AI is a good way to cheat and kind of inflate the size of your crowd,” Smith said.

He added there’s also a flip side to this phenomenon. “If there’s a real image that surfaces and it shows something that’s politically inconvenient or damaging, there’s also going to be a tendency to say, ‘no, that’s an AI fake.'”

One example of this occurred in August 2024, when then-Republican Party nominee Donald Trump spread false claims that Democratic rival Kamala Harris’s team used AI to create an image of a big crowd of supporters.

Chapman University lecturer Charlie Fink, who writes about AI and other emerging technologies for Forbes, said it’s especially easy to dupe people into believing a fake crowd scene is real or a real crowd scene is fake because of how the images are delivered. “The challenge is that most people are watching content on a small screen, and most people are not terribly critical of what they see and hear. ” Fink said. “If it looks real, it is real.”

Balancing creativity with public safety

For the technology companies behind the AI image generators and social media platforms where AI-generated stills and videos land, there’s a delicate balance to be struck between enabling users to create ever-more realistic and believable content – including detailed crowd scenes – and mitigating potential harms.

“The more realistic and believable we can create the results, the more options it gives people for creative expression,” said Oliver Wang, a principal scientist at Google DeepMind who co-leads the company’s image-generation efforts. “But misinformation is something that we do take very seriously. So we are stamping all the images that we generate with a visible watermark and an invisible watermark.”

However, the visible – that is, public-facing – watermark currently displayed on videos created using Google’s Veo3 is tiny and easy to miss, tucked away in the corner of the screen. (Invisible watermarks, like Google’s SynthID, are not visible to regular users’ eyes; they help tech companies monitor AI content behind the scenes.)

And AI labeling systems are still being applied rather unevenly across platforms. There are as yet no industry-wide standards, though companies NPR spoke with for this story said they are motivated to develop them.

Meta, Instagram’s parent company, currently labels uploaded AI-generated content when users disclose it or when their systems detect it. Google videos created using its own generative AI tools on YouTube automatically have a label in the description. It asks those who create media using other tools to self-disclose when AI is used. TikTok requires creators to label AI-generated or significantly edited content that shows realistic-looking scenes or people. Unlabeled content may be removed, restricted, or labeled by our team, depending on the harm it could cause.

Meanwhile, Will Smith has been having more fun with AI since that controversial concert video came out. He posted a playful followup in which the camera pans from footage of the singer performing energetically on stage to reveal an audience packed with fist-pumping cats. Smith included a comment: “Crowd was poppin’ tonite!!”

Transcript:

SCOTT DETROW, HOST:

This Will Smith video tore through the internet recently…

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

WILL SMITH: (Rapping) So dry your eyes and then you’ll find a way.

DETROW: …Not for his performance, but for the crowd. Eagle-eyed viewers noticed odd fingers and faces among the fans and suspected AI manipulation. Crowd scenes, like at concerts, rallies and protests, have long tripped up AI systems, but buckle up because the tech is getting better. NPR’s Chloe Veltman has more.

CHLOE VELTMAN, BYLINE: Will Smith’s team hasn’t publicly commented on how the video was made, but San Francisco-based visual artist and researcher Kyt Janae, an expert on AI image creation, says AI was used in places. She dropped by recently to point out where.

KYT JANAE: That woman’s real. That reaction’s real. That’s not real.

VELTMAN: Janae pauses the video when she comes across glitches in the audience footage.

JANAE: We’ve got these very long fingers sort of melting into this woman’s face. And then it seems like there’s – maybe her neck is meshing into somebody’s hair.

VELTMAN: Janae says these weird effects are happening because crowd scenes present a particular technological challenge for AI image creation tools.

JANAE: You’re managing so many intricate details. You have each individual human being in the crowd.

VELTMAN: They’re all moving independently and have unique features. But Janae says AI models, such as Google’s Veo 3 and OpenAI’s Sora 2, are getting pretty good.

JANAE: We’re moving into a world where, in a generous time estimate of a year, the lines of reality are going to get really blurry, and verifying what is real and what isn’t real is going to almost have to become like a practice.

VELTMAN: And Janae’s observation could potentially have serious consequences in a society where images of big, engaged crowds at public events like rock concerts, protests and political rallies have major currency. Thomas Smith is the CEO of Gado Images. The company uses AI to help manage visual archives.

THOMAS SMITH: We want a visual metric, a way to determine whether somebody is succeeding or not. And crowd size is often a good indicator of that.

VELTMAN: A report from consulting firm Capgemini shows nearly three-quarters of images shared on social media in 2023 were generated using AI. With the technology becoming increasingly adept at creating convincing crowd scenes, manipulating visuals has never been easier. With this, Smith says, comes both a creative opportunity and a societal hazard.

T SMITH: AI is a good way to cheat and kind of inflate the size of your crowd.

VELTMAN: He adds there’s also a flip side to this phenomenon.

T SMITH: If there’s a real image that surfaces and it shows something that’s politically inconvenient or damaging, there’s also going to be a tendency to say, no, that’s an AI fake.

VELTMAN: Like in August 2024, when then-Republican Party nominee Donald Trump spread false claims that Democratic rival Kamala Harris’ team used AI to create an image of a big crowd of supporters. Chapman University emerging technologies lecturer Charlie Fink says it’s especially easy to dupe people into believing a fake crowd scene is real or a real crowd scene is fake because of the mode of delivery.

CHARLIE FINK: The challenge is that most people are watching content on a small screen. And most people are not terribly critical of what they see and hear. If it looks real, it is real.

OLIVER WANG: The more realistic and believable we can create the results, the more options it gives people for creative expression.

VELTMAN: Oliver Wang is a principal scientist at Google DeepMind. He co-leads the company’s image-generation efforts. Wang says a balance needs to be struck between enabling users to create ever more realistic and believable content, including detailed crowd scenes, and mitigating potential harms.

WANG: Misinformation is something that we do take very seriously. So we are stamping all the images that we generate with a visible watermark.

VELTMAN: However, this watermark is tiny and easy to miss. And AI labeling systems, including invisible watermarks, which Google also uses, are still being applied rather unevenly across platforms. There are still no industry-wide standards.

Meanwhile, Will Smith has been having more fun with AI since that controversial concert video came out. He posted a playful follow-up.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

W SMITH: One, two, three, go.

VELTMAN: The camera pans from footage of the singer performing energetically on stage to an audience packed with fist-pumping cats.

Chloe Veltman, NPR News.

(SOUNDBITE OF LOLA YOUNG SONG, “CONCEITED”)

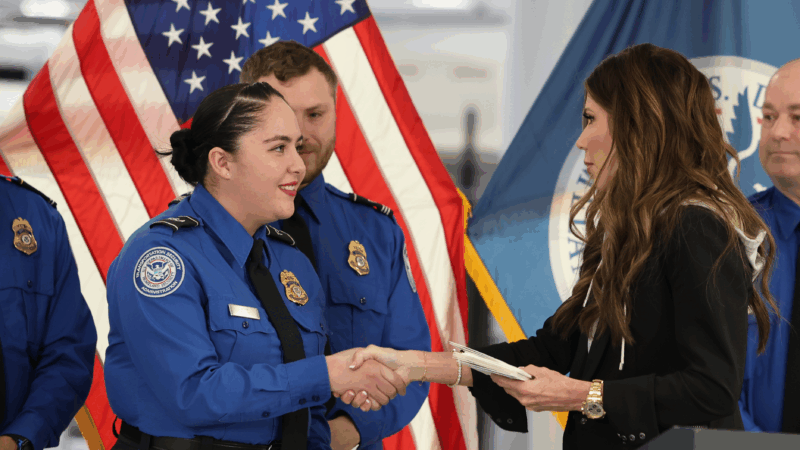

Homeland Security suspends TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is suspending the TSA PreCheck and Global Entry airport security programs as a partial government shutdown continues.

FCC calls for more ‘patriotic, pro-America’ programming in runup to 250th anniversary

The "Pledge America Campaign" urges broadcasters to focus on programming that highlights "the historic accomplishments of this great nation from our founding through the Trump Administration today."

NASA’s Artemis II lunar mission may not launch in March after all

NASA says an "interrupted flow" of helium to the rocket system could require a rollback to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If it happens, NASA says the launch to the moon would be delayed until April.

Mississippi health system shuts down clinics statewide after ransomware attack

The attack was launched on Thursday and prompted hospital officials to close all of its 35 clinics across the state.

Blizzard conditions and high winds forecast for NYC, East coast

The winter storm is expected to bring blizzard conditions and possibly up to 2 feet of snow in New York City.

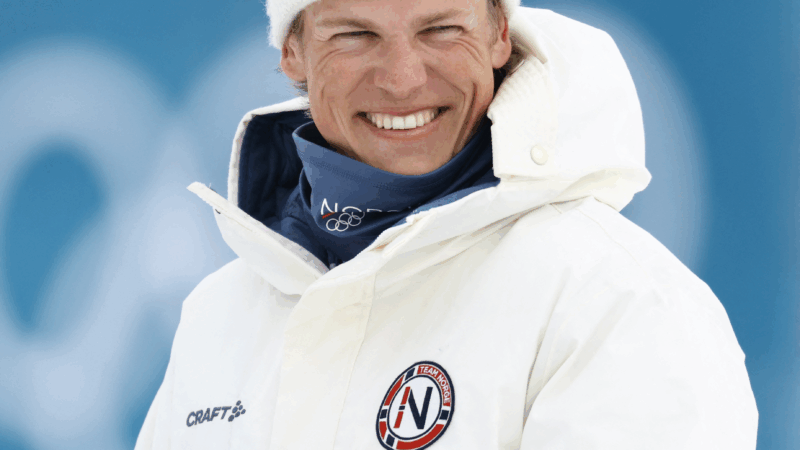

Norway’s Johannes Klæbo is new Winter Olympics king

Johannes Klaebo won all six cross-country skiing events at this year's Winter Olympics, the surpassing Eric Heiden's five golds in 1980.