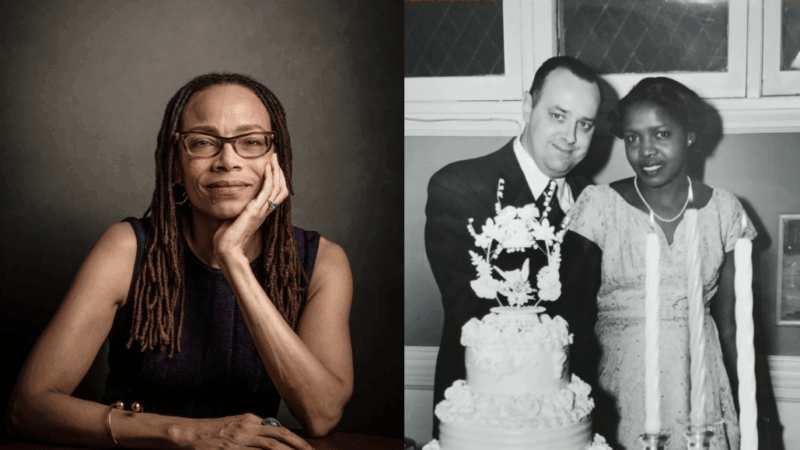

A daughter reexamines her own family story in ‘The Mixed Marriage Project’

Almost a decade after her father’s death, legal scholar Dorothy Roberts still had 25 boxes of his research that she had yet to sort through. When she moved from Chicago to Philadelphia, she brought the boxes — and finally opened them.

Roberts’ father, Robert Roberts, was a white anthropologist who spent his career at Roosevelt University in Chicago. The boxes contained transcripts of nearly 500 interviews he had conducted with interracial couples across the city, including interviews with couples who were married in the late 1800s, all the way to couples who are married in 1960s.

“They were absolutely fascinating,” Roberts says of the transcripts. “I learned so much about the racial caste system in Chicago, the Color Line, the Black Belt.”

Initially, Roberts saw the project as a chance to finish her father’s work, but as she examined the documents, she learned more about her own family — including the fact that her mother Iris, a Black Jamaican immigrant, had assisted in her husband’s research.

“When I got to the 1950s interviews, I discovered that my mother was conducting all the interviews of the wives, while my father conducted the interviews for the husbands,” Roberts says. “Finding out that my mother was involved … created curiosity I had about my family, about their marriage, and then I began to think about how it related to me and my identity as a Black girl with a white father.”

In her new book, The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir of Love, Race, and Family, Roberts dives into her parents’ research, and her surprise at learning that she was included as participant number 224 in the files. She also shares her own thoughts on interracial relationships.

“My father thought that interracial intimacy was the instrument to end racism, and I think it’s really flipped the other way,” she says. “We end racism when we will see the possibility of truly being able to love each other as equal human beings.”

Interview highlights

On white European immigrant women marrying Black men in the early 20th century

These were immigrant women coming from Europe who had no familiarity at all with the racial caste system in Chicago. … So when they marry Black men, in fact, they thought that marrying an American citizen would help them assimilate into American culture. So they had no idea … that if they married a Black man, it would do the opposite to them. They would be lower in their status than they were as white immigrants. And so many of them would say, “I found out that I had to live in a colored neighborhood. I had to leave my white neighbors, I had left my family in order to marry this Black man and move into the Black Belt. I now couldn’t even tell my employer my address, because if they found out my address they’d know I must be living with a Black man.” Why else would a white woman be living in the Black Belt?

They were afraid they would lose their jobs, and many reported that they were fired as a result of their employer finding out that they were married to a Black man. They were met with stares when they got on the streetcar. Many said that if they were going on a streetcar in Chicago, they would go on separately and pretend they didn’t know each other so that no one would know that they were married.

On the difference between her father and mother’s notes in the project

My father, much to my horror, was very anthropological in terms of the physical traits of the people he interviewed. He wrote about the “Negroid traits” and whether the child had any trace of “Negroid blood” and that sort of thing. Again, remembering he was doing this in the 1930s.

My mother was much more interested in the personality traits of the people she interviewed and what their furniture looked like and her own emotions. And there’s just so many delightful things. The way in which she interacts with the children when she’s interviewing the wives, there’s a lot more attention to what the children are doing. I can’t remember a single interview where my father really describes the children’s behavior. He describes their physical appearance, but my mother would describe their behavior and their interaction with the mother. All of that is part of the interview and her notes and she writes it almost like a screenplay. It’s really, really wonderful to read.

On the fetishization of interracial intimacy and biracial children

There was this visceral feeling I felt whenever a Black man, a Black husband, would talk about his preference for being with white women. These ideas that interracial intimacy has an extra excitement to it. It has an extra titillation to it, that kind of idea came up in many of the interviews, and I just have a very visceral revulsion at that kind idea, a sort of a fetishization of interracial intimacy and also of biracial children. The idea that whitening children makes them more attractive or makes them more intelligent or more appealing, more lovable. And whenever that came up, I just, sometimes I had to just throw the interview down because I couldn’t stand that kind of thinking.

On her decision to identify as Black in college and hide her dad’s whiteness

I am a Black woman with a white father. … I would have not done the [work] to uplift Black women if it weren’t for my father and all that he taught me.

Dorothy Roberts

I now regret that I hid the fact that my father was white, that I denied him that part of my identity, or denied the reality that he was part of my identity. … I think I very wrongly believed that if they knew my father was white, I somehow wouldn’t be as much an integral part of these groups that they might feel differently about me. …

I realized by the end of working on the memoir that I am a Black woman with a white father [and] I should not deny all that my father contributed to my identity. I would not be the Black woman I am today, I probably would not have done the work against racism and against the demeaning of Black women, I would have not done the [work] to uplift Black women if it weren’t for my father and all that he taught me. And I need to appreciate and acknowledge all that my father contributed to the Black woman I am today.

On what this project has taught her about love and race

It showed me more powerfully than anything I’d ever read before how the invention of race, the lie that human beings are naturally divided into races, can erase the very ties of family. … In my own case, my father’s younger brother, my uncle Edward, disowned him when he married my mother. And even though he lived in the Chicago area and I had cousins who lived there, I never met them because of this rift, this divide between my father and his brother.

Working on the memoir also made me realize that all the work I’ve been doing throughout my career was trying to answer this question of, what does it take to love across the chasm of race? That’s what these couples are telling us, even the ones who were still racist, … they’re telling us what it takes to challenge and dismantle structural racism in America. And so, to me, these interviews persuaded me even more that we can believe in our common humanity. We can overcome the seemingly unbreakable, unshakable shackles of structural racism. But it can’t be simply by pretending that the sentiment of love or even loving someone across the racial lines will do it. We have to see the work that it’s going to take to do that.

Anna Bauman and Nico Gonzalez Wisler produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.

Transcript:

TONYA MOSLEY, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. And my guest today is legal scholar and author Dorothy Roberts. For decades, Roberts has challenged the idea that institutions, like medicine, the law, and child welfare, are neutral. Her landmark books, “Killing The Black Body” and “Torn Apart,” helped reshape how we understand the policing of reproduction, parenting and race in America. Her new book now turns that lens inward. It begins with 25 boxes of her late father’s papers.

Robert Roberts was a white anthropologist who spent his career at Roosevelt University in Chicago and over the course of 50 years conducted hundreds of interviews with interracial couples across the city, an extraordinary archive dating back to the 1930s. Her mother, Iris, a Black Jamaican immigrant, was his wife. And what Roberts finds inside those boxes challenges the story she’d always believed about her own family.

Roberts is a professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2024 MacArthur fellow. The memoir is called “The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir Of Love, Race, And Family.” Dorothy Roberts, welcome to FRESH AIR.

DOROTHY ROBERTS: Thank you so much, Tonya. It’s such a pleasure to be on this program.

MOSLEY: A pleasure to have you. And let’s start with these 25 boxes because you tell us right from the start of the book that they were sitting in your basement for almost a decade after your parents died. And the date on the first transcript is February 1937. And this date stopped you in your tracks. You actually described feeling frozen, kind of like you were going to faint as you clutched those papers to your chest. What was it about that date in particular that undid you?

ROBERTS: Well, I always assumed that my father was writing his book on interracial marriage, conducting the interviews that were the basis of this book he was working on in the 1960s while I was growing up. I have very vivid memories of him conducting the interviews and being up in his study on the third floor writing the book. It really dominated my childhood. And so I assumed because of that that he got interested in interracial marriage and wanted to learn the stories of Black-white couples because he met and fell in love with my mother, which happened in the 1950s. And so now, discovering this transcript of an interview from 1937, it just completely upended my understanding of my father’s research and its relationship to my family.

You know, I’m thinking, well, first of all, how in the world did my father even get interested in this topic when he was only 21 years old, having grown up in a segregated white neighborhood in Chicago, being so young? I just – it was a mystery to me. But then, in addition to that, it really flipped the relationship I thought he had with my mother and his research because now I knew it wasn’t that his falling in love with my mother and marrying her motivated him to do this research. It might have been the opposite – that he was first interested in interracial marriage, and then he married my mother.

MOSLEY: That made you sit with some really uncomfortable and complicated feelings and grapple with some things about whether your father was really attracted to your mother for who she was or if it was because he was looking for a Black woman to date and then ultimately marry. And you finally came to some conclusions, which makes the book just so striking.

But your father had tried for decades to turn all of this research into a book. He had a deal with Simon & Schuster and another publication. So you went into this thinking, as you’re opening those pages and reading and discovering, that maybe you might finish the work that he had done. But when did you realize that the book you needed to write wasn’t exactly his work?

ROBERTS: Yes, you’re right. I first thought, I’ll finish the book that my father never published, because I found nearly 500 interviews in these boxes, and they were absolutely fascinating, including interviews with couples who were married in the late 1800s, you know, all the way to couples who were married in the 1960s. And all of the stories were so intriguing. I learned so much about the racial caste system in Chicago, the color line, the Black Belt. All of this could make a fascinating book, I thought. And that was my first plan.

But as I immersed myself in the interviews, I began to learn more about my father because the very questions he asked, his notes in the transcripts, finding out that my mother was involved, you know, all of this created a curiosity I had about my family, about their marriage. And then I began to think about how it related to me and my identity as a Black girl with a white father. And the more and more I delved into the interviews and thought about the meaning for me and my family and my identity, I was just compelled to write a book about that. And so it turned from a kind of sociological or anthropological study of couples – Black-white couples in Chicago over several centuries into an exploration of my own family and my own identity.

MOSLEY: Yeah. I want to – before we get to all of those points, I really want to understand a little bit more about who your father was because here he is training as an anthropologist in the 1930s, but at 16, your father would spend several months in a village in Northeast India, where he watched caste dictate who could marry whom. And do you think – do you suspect that is where he was able to see more clearly the systems in place in the United States and sort of draw that line?

ROBERTS: Yes, I think there had to be a connection. He traveled around the world, literally, with his grandmother on this trip to and from India. And he writes in his diary about making friends with tribal boys in India. He writes about wearing the clothing that they gave him, all of this without any sense of judgment whatsoever. And then when he gets to college, I find some of his papers where he talks about his white privilege. He’s challenging the professors, you know, who believe that white – in white superiority. Basically, they believe in inherited traits that determine how capable you are. My father writes, I don’t believe that. That’s not true. Everyone is just as capable. It’s just that I have the benefit of people not discriminating against me because of my Nordic heritage – and when he was 17. So he was already, for some reason, open to the idea that there was a racial caste system in Chicago, like the one in the South, he writes, and that it could be dismantled. He also had the mission of ending racial caste. He thought it could be done through interracial marriage. But that was his ultimate mission.

MOSLEY: Let’s get into some of the transcripts. So the questions your father asked in the 1930s, they really reveal so much about what these couples were up against. And one of the women your father interviewed was Mrs. Tyler (ph).

ROBERTS: Yes.

MOSLEY: She’s described as a Bohemian immigrant who spent her 16th birthday on Ellis Island. She married a Black man in Chicago, barely speaking English, not a lot of understanding about America’s racial hierarchy. And there’s a passage where she reveals this to your father, really with painstaking clarity. Can I have you read it?

ROBERTS: (Reading) The racial hierarchy that had eluded Mrs. Tyler became painfully clear soon after her wedding in March 1928. A cab driver asked if she wasn’t afraid to be dropped off in the colored section. She was turned away when she tried to stay at a hotel with her husband. When I came, I thought it was free for everybody. That’s what they said about America in the old country. That isn’t true, she said. I don’t think I ever would have married as I did if I knew all this. I wouldn’t have the nerve.

MOSLEY: Thank you for reading that. And I want to take this even further ’cause there’s a phrase that Mrs. Tyler uses where she says she feels like an innocent criminal to be married to a Black man. Your father ended all of these interviews with this same question. He asked everyone – if you had your life to live over, would you marry the same person? And you noticed women like Mrs. Tyler – when they were alone speaking to your father, their answers, especially white women, changed depending on whether their husband was in the room. What were some of the things that they shared that kind of bolstered, almost, what Mrs. Tyler is saying here about her surprise?

ROBERTS: Well, you have to understand that these were immigrant women coming from Europe who had no familiarity at all with the racial caste system in Chicago. And as Mrs. Tyler said, she thought – she had heard – that America was a land of freedom. So when they marry Black men, in fact, they thought that marrying an American citizen would help them assimilate into American culture.

So they had no idea, women like Mrs. Tyler from Europe, that if they married a Black man, it would do the opposite to them – they would be lower in their status than they were as white immigrants. And so many of them would say, I found out that I had to live in a colored neighborhood. I had to leave my white neighbors. I had to leave my family in order to marry this Black man and move into the Black Belt. I now couldn’t even tell my employer my address because if they found out my address, they’d know I must be living with a Black man. Why else would a white woman be living in the Black Belt? They were afraid they would lose their jobs. And many reported that they were fired as a result of their employer finding out that they were married to a Black man.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, my guest is Dorothy Roberts. She’s a legal scholar, MacArthur Fellow and the author of several books on race in America. Her new memoir, “The Mixed Marriage Project,” tells the story of her parents’ interracial marriage and the nearly 500 transcripts her white father left behind from decades of interviewing Black and white couples in Chicago. We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. Today, we’re talking to Dorothy Roberts, professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2024 MacArthur fellow. Her new memoir, “The Mixed Marriage Project,” is built around her discovery of her late father’s research – decades of interviews with interracial couples in Chicago – and forces her to reckon with her own conclusions about her father’s scholarship.

I want to stay in the 1930s because your father didn’t just collect interviews. He found his way into that world. And one of the most fascinating discoveries in the transcript is the Manasseh Society. It’s a social club for interracial couples in Chicago. But even inside this community, which is built around love across the color line, there is a hierarchy. Who was welcome and who wasn’t?

ROBERTS: That’s right. My father soon discovers, when he starts collecting the names and backgrounds of members because he wanted to interview them, that Black women were almost entirely excluded. Now, it is true that there were more white women married to Black men.

MOSLEY: And why do you – why was that?

ROBERTS: Well, that’s a question we could ask today. You know, why is it that, you know, even today it’s more common that white women will marry Black men than white men will marry Black women? And that was true at the time my father was conducting interviews in the 1930s as well. So some of it is just statistical. It – there were just more of the couples that were white women and Black men in Chicago. But from the statements that the white wives make when my father presses them on why there was this absence of Black women from their club, they say horrible things about Black women. They say, well, we don’t really like Black women because they have looser morals.

And this was a theme that cut throughout the 1930s interviews – the fact that they, many, many of the couples, mentioned that white men were having sex with Black women but weren’t marrying them. And what these wives in the Manasseh Society and some of – actually, some of the Black men as well were saying was the reason why white men are sleeping with Black women but not marrying them is because Black women are so licentious, they don’t require marriage. So they blamed Black women for the rarity of white men marrying Black women instead of looking for other reasons why. You know, my father suggested, well, maybe it’s because they’re looked down on – these marriages are looked down on so much. I also wonder if part of it is the privileges that white men would lose when they married a Black woman.

MOSLEY: Well, I mean, you make this very striking observation that Black men who loved white women, especially in these transcripts, may have really felt like they were opposing white supremacy, while for many Black women, interracial intimacy overall has never really looked like liberation. And your father’s notes are kind of quiet on this. I mean, he was a white man attracted to Black women, which on its own is kind of a breach of taboo. But he doesn’t name the contradiction. And I wondered if you read that silence as diplomacy or something else.

ROBERTS: Yeah, I often wondered what my father thought when he’s hearing all these stereotypes about Black women. And he made it very clear in the interviews from in his early 20s, he was already attracted to Black women and was dating Black women and bringing them to parties and that kind of thing, looking for Black women to dance with and all of that. And so I wondered what he thought when he heard these disparaging comments about Black women, and he never really said anything.

There was one time when he did kind of lash out at a white daughter – well, she was actually a biracial daughter of a Black man he interviewed. But she liked to think of herself as being able to pass as white, and she was happy that her children could pass as white. And she said she couldn’t understand how white women would marry a Black man and potentially have children who were colored. You know, and my father lashed out at her, the only time I saw ever in the interviews that he really got angry (laughter) with someone and said, you shouldn’t get so upset, you know, when we talk about interracial relationships.

MOSLEY: Your mother, Iris, she was an educated, Black Jamaican woman. And she was also your father’s research partner.

ROBERTS: (Laughter) Yeah.

MOSLEY: She conducted interviews alongside him. She wrote a lot of the field notes. You, though, did not grow up knowing any of this. How did discovering her role change the story you told yourself about your parents?

ROBERTS: Yes, that was another major discovery I made in the interviews. When I got to the 1950s interviews, I discovered that my mother was conducting all the interviews of the wives while my father conducted the interviews of the husbands. And I had no idea that my mother was so involved in the research. She was tracking down some of these couples. She was interviewing them. She was writing up her notes and typing up the transcripts.

And it really changed my view of the whole project because, growing up, it was always Daddy’s book. You know, she was cheering him on. In fact, she was more interested in him publishing this book than he was. (Laughter) You know, she was constantly telling him…

MOSLEY: Yeah. Pushing him, yeah.

ROBERTS: …Bob, finish the book, finish the book, because she was very ambitious. And she had given up her Ph.D. work in order to have me and my sisters and raise us. And she supported his work in so many ways. And so, I could see now, after discovering her deep involvement in the research, why she was so frustrated (laughter).

MOSLEY: Well, what did your mom actually write in those field notes? What was her voice like as a researcher in comparison, maybe, to your dad’s voice?

ROBERTS: Yeah, I was so delighted to see my mother’s voice in the notes and the very way she wrote up the interviews, because while my father, much to my horror, was very anthropological – in terms of the physical traits of the people he interviewed. You know, he wrote about the negroid traits and whether the child had any trace of negroid blood and that sort of thing. Again, remembering he was doing this in the 1930s. My mother was much more interested in the personality traits of the people she interviewed and what their furniture looked like, and her own emotions. And there’s just so many delightful things.

The way in which she interacts with the children when she’s interviewing the wives, there’s a lot more attention to what the children are doing. I can’t remember a single interview where my father really describes the children’s behavior. He describes their physical appearance, but my mother would describe their behavior and their interaction with the mother. All of that is part of the interview and her notes, and she writes it almost like a screenplay. It’s really, really wonderful to read.

MOSLEY: Our guest today is author and scholar Dorothy Roberts. We’ll be right back after a short break. I’m Tonya Mosley, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ERIC DOLPHY AND BOOKER LITTLE’S “MRS. PARKER OF K.C. (BIRD’S MOTHER)”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley, and I’m continuing my conversation with Dorothy Roberts, a professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2024 MacArthur Fellow. Over a career spanning more than three decades, Roberts has written some of the most influential books on race in America – “Killing The Black Body” on reproductive control, “Fatal Invention” on the myth of biological race and “Torn Apart” on the child welfare system. Her new memoir, “The Mixed Marriage Project,” turns the lens on her own family. In it, she documents her father’s extraordinary archive of nearly 500 interviews with interracial couples in Chicago and the lesson she pulled from it as a Black woman in America.

How did this make you grapple with your own thoughts about interracial relationships? Of course, you grew up with your parents and lots of couples around you who were interracial, and so there is an acceptance there. But, I mean, inherently, as a Black woman in America, how did these transcripts kind of make you grapple with your own feelings about it?

ROBERTS: Oh, I grappled with my own feelings with every single interview I read in so many – multiple levels. There was this visceral feeling I felt whenever a Black man, a Black husband, would talk about his preference for being with white women. You know, these ideas that interracial intimacy has an extra excitement to it, it has an extra titillation to it – that kind of idea came up in many of the interviews, and I just have a very visceral revulsion. That kind of idea – it’s sort of a fetishization of interracial intimacy and also of biracial children, the idea that whitening children, you know, is – makes them more attractive or makes them more intelligent or more appealing, more lovable. I – and whenever that came up, I just – sometimes I had to just throw the interview down because I couldn’t stand that kind of thinking.

MOSLEY: Do you think that some of your – that visceral reaction and feeling to the Black men in the transcripts talking of how they felt kind of, like, titillated by it, by the idea of dating outside of their race – it feeling like a rejection of self for you?

ROBERTS: Yes. It’s when the Black men would describe their feelings for white women in a way that they couldn’t possibly have toward Black women because Black women are Black. You know, the – for example, Mr. Sussex, whom I suspect was my piano teacher – he said that when he found out he could date white women, they became more attractive to him than Black women. He stopped dating Black women when he found out he could date white women. It wasn’t that finding out he could date white women expanded the range of women he could date. It was that it was a rejection of Black women.

Now, there’s also this complexity to it that because Black men were punished, lynched, killed for even showing some attention to white women, you know, based on the accusation that they had sex with a white woman, I can see how Mr. Sussex is now saying, all right. My ability to date white women is in defiance of that history. So it seems as if it’s something that is challenging white supremacy, whereas the history for Black women is sexual exploitation, rape by white enslavers. And so for many people, when Black women love white men or white men love Black women, it’s – and this came out in the interviews – it seems as if it’s just a continuation of white supremacist, patriarchal power of white men. And I don’t think that that’s necessarily the case.

You know, I can see in my own family, my father revered, respected my mother. He loved her. He was committed to her. And throughout reading these interviews, what I always wanted to do and what I felt most strongly about was challenging all the ways that Black women have been demeaned, have been vilified – our sexuality, our childbearing, our mothering. You know, that’s what my whole career has been about. And I really did have a very strong reaction against every time that kind of thinking came up in the interviews.

MOSLEY: There’s a moment in the book I’d love for you to read. You’re going through the boxes in your office, and you find a folder. And the folder had a number on it – 224. And can I have you read from there?

ROBERTS: (Reading) Inside are four documents – a college paper I submitted for a sociology class, two versions of an essay I wrote, one in longhand, the other typed, and a typed letter my father wrote to me. I feel dizzy as the realization sets in. I am research participant No. 224. Daddy had created a file on me and placed it among the folders containing notes and transcripts from his interviews with other children of interracial couples.

By now, I know that his fascination with interracial families began long before he started one of his own. I have long understood that my mother, my sisters and I were inextricably tied to his scholarly obsession, woven into his lifelong pursuit of interracial intimacy. But discovering that he considered me an actual subject of study? That was a whole new level of entanglement. I begin to wonder – was I born entirely from his love for my mother, or was I in some way an extension of his mission to document and popularize mixed marriages? It unsettles me to think that my sisters and I may have been unwitting guinea pigs in a social experiment designed to prove the viability and perhaps even the superiority of interracial unions.

MOSLEY: Thank you for reading that. And I want to ask you, what did that discovery, first off, do to you? And what answers did you come to after sitting with that discovery?

ROBERTS: At first, I was really shocked to find that I was a participant, a research subject in his study now of the children of interracial couples. And I did wonder initially, was I part of an experiment of his, trying to prove his theory that biracial children were well-adjusted and weren’t tragic mulattos, that we could do well in school and do well in society? But, you know, I was so close to my father. I knew how much he loved me. I was so entangled in his work because he brought it into our family’s life. And he discussed it with me so much. And so I knew that his including me in the project was not because he thought of me just as a research subject, but because he thought of me as part of his entire life’s work.

And I began to realize that that actually made him even closer to me. It meant that I was even closer to him. I was involved in every aspect of his life. You know, there are lots of children who feel separated from their parents and separated from their parents’ work and even feel that their parents’ work is more important to them, to their parents, than they are. I never felt that way about my father. I always felt that I was essential to him.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, my guest is Dorothy Roberts. Her new memoir is called “The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir Of Love, Race, And Family.” We’ll be right back after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JOHN COLTRANE QUARTET’S “OUT OF THIS WORLD”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. Today, we’re talking to Dorothy Roberts, professor of law and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania and a 2024 MacArthur fellow. Her new memoir, “The Mixed Marriage Project,” is built around her discovery of her late father’s research and forces her to reckon with her own conclusions about her father’s scholarship.

Your father’s thesis was that if interracial unions were allowed to flourish, they would prompt demands for social equality, that basically interracial marriage could help dismantle this caste system that he believed America was under. Do you think that there was something he could not see precisely because of where he stood and something that you could see precisely because of where you stand?

ROBERTS: Ah, certainly, we had debates throughout even my childhood about whether or not interracial marriage could dismantle racism. And I…

MOSLEY: Really? Do you remember when was the first time you all had that debate?

ROBERTS: Well, it began not so much with a debate, but with his trying to persuade me of his views. That began very early. I mean, as early as I can remember, my father was trying to persuade me that the answer to America’s race problem was interracial marriage. And he told me that over and over and over again. Along with, I have to say, his main message was that all human beings are equal, there’s only one human race, and the only reason why Black and white people are not moving together for greater racial justice is because of invented divisions between us. So that was his main message, and that I agree with to this day.

But the idea of the power of interracial love by itself was something I began to question. I don’t remember exactly when. But I know for a fact that when I read “Black Power,” by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton, when I was in seventh grade, that I began to have a very different perspective than my father. I do believe that, beginning at that young age, I recognized the power of structural racism and could not accept his view that interracial love by itself would be strong enough to transcend it or overcome it or dismantle it.

ROBERTS: And so from that time on, we began to have debates about it. But, you know, my father always respected my opinion. That’s something I also learned in the file that I found about me, that he kept this file, even though the file contained wording that adamantly disagreed with him. But he still kept it, and he still loved me, and he still respected my opinion.

MOSLEY: How did those conversations influence your own dating life as a young person?

ROBERTS: (Laughter) Well, the biggest influence on my dating life until I went to college was my mother, who wouldn’t allow me to date because she wanted to make sure that I focused solely on my studies. I have only dated Black men, and it’s hard to say how my parents’ marriage or my father’s research or my conversations with my father influenced that. But I have just been attracted to Black men. And maybe in relationships with Black men, it could also be that Black men found me attractive and gravitated toward me, as well as my gravitating toward them.

MOSLEY: Why do you think it’s so hard to untangle the why?

ROBERTS: You know, this is something I really struggle with. The very question of what is the role of race in the first place in whom we find attractive, you know, whom we decide to date and marry. Isn’t it the case that when you marry someone or find someone attractive of your own race, that it depends partly on race? You know, so I kept asking myself, is it different than if you find someone attractive of – from another race, or even if you only find people of another race attractive?

You know, I have always been in relationships, intimate relationships with Black men. Is that because I find Black men attractive, and is that because I’m choosing them based on race? And is that different from if I found white men attractive and dated white men and chose to marry a white man based on race? Somehow I think there’s a difference, but I’m – it’s hard to say, partly because these are emotions and feelings that it’s difficult to figure out where they come from. You know, it – you can’t really do a sociological study of it. And that’s just part of the – you know, the nuance, the complexity, the mystery around this topic of interracial intimacy and interracial marriage.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, my guest is Dorothy Roberts. Her new memoir is called “The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir Of Love, Race, And Family.” We’ll be right back after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ROBBEN FORD & BILL EVANS’ “PIXIES”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. And today, we’re talking to Dorothy Roberts, the acclaimed legal scholar and MacArthur Fellow. Her new memoir, “The Mixed Marriage Project,” is her most personal work, built on the discovery of her father’s nearly 500 interview transcripts with interracial couples.

In college, you not only identified as Black, but you tried to hide that your father was white. And what did this book force you to confront about that choice?

ROBERTS: Yes. I now regret that I hid the fact that my father was white, that I denied him that part of my identity or denied the reality that he was part of my identity. I found that what I wrote to him, for his eyes, was extremely hurtful. I could hardly believe that I wrote to my father that I had hid that he was my father because he’s white. I couldn’t…

MOSLEY: At the time, do you feel like you were trying to hurt him? Do you remember why you did that?

ROBERTS: I think I was just trying to write the reality of how I felt. I’m – I believe that my father must have asked me to write an essay about my racial identity that he would put in a file about me. I mean, I didn’t know he would put it in the file, but he wanted me to write about it for him to read. And, you know, I didn’t know he had a file on me. But when I wrote that – and I don’t remember exactly my feelings, but I’m pretty sure I thought, my father is researching this, and he wants to know how his daughter feels about it. And so I wrote very honestly what I felt at the time.

This – I was a first-year student in college, or perhaps this was the summer after I finished my first year. And that was the year that I was so intent on making sure I could be part of this group of Black students and – I think very wrongly – believed that if they knew my father was white, I somehow wouldn’t be as much an integral part of this group, that they might feel differently about me. I think I was wrong about that, and now that feeling seems so strange to me. But I did have to grapple with it when I came across what I had written in that essay and also just in general, reading these interviews, thinking about my father and my shifting identity to – not wanting to think of myself as mixed, as – or even just as human, as my parents taught me to think, but to really identify as a Black woman.

And I realized by the end of working on the memoir that I am a Black woman with a white father. I should not deny all that my father contributed to my identity. I would not be the Black woman I am today. I probably would not have done the work against racism and against the demeaning of Black women. I would not have done the work to uplift Black women if it weren’t for my father and all that he taught me, and I need to appreciate and acknowledge all that my father contributed to the Black woman I am today.

MOSLEY: You know, your 2011 book, “Fatal Invention” – I want to talk about it just for a moment in the context of this work because you argued that race is a political category, something Europeans invented to oppress other groups. You’ve talked about that through our conversation, and your father spent all this time really believing that interracial relationships could dismantle that system. But your book made me see that this designation doesn’t just sort people. It severs families.

You write about children who looked Black, were forced to live in a different part of the city than their white mother and brother, who had married white. And so they had the same blood, but they were different sides of the color line because one part of the family could pass and the other could not. And so many Americans, including myself, have white blood relatives in this country whom we will never know to this very day because of that false construct. The designation is what makes us strangers. So I’m just wondering – what did this project teach you about the limits of really what love can do?

ROBERTS: It showed me more powerfully than anything I’d ever read before how the invention of race, the lie that human beings are naturally divided into races, can erase the very ties of family. And that might be the most striking evidence of just how overwhelming, how powerful the belief in race is. The fact that it can take a family that is related to each other, you know, by blood, by genetics, whatever term you want to use, and erase that relationship is an extremely, extremely powerful and insidious way that race can operate.

In my own case, my father’s younger brother, my uncle Edward, disowned him when he married my mother. And even though he lived in the Chicago area and I had cousins who lived there, I never met them because of this rift, this divide between my father and his brother. And so working on the memoir also made me realize that all the work I’ve been doing throughout my career was trying to answer this question of, what does it take to love across the chasm of race?

You know, that’s what these couples are telling us, even the ones who were still racist, you know? Even though the – both the ones who were racist and the ones who challenged racism – it – they’re telling us what it takes to challenge and dismantle structural racism in America. And so, to me, these interviews persuaded me even more that we can believe in our common humanity. We can overcome the seemingly unbreakable, unshakable shackles of structural racism. But it can’t be simply by pretending that the sentiment of love or even loving someone across racial lines will do it. We have to see the work that it’s going to take to do that. You know, my father thought that interracial intimacy was the instrument to end racism. And I think it’s really flipped the other way that as we end racism, that’s when we will see the possibility of truly being able to love each other as equal human beings.

MOSLEY: Dorothy Roberts, thank you so much for this scholarship, for this book and for this conversation.

ROBERTS: Thank you, Tonya. It’s been really a delight and an honor to be able to speak with you. I really, truly appreciate it.

MOSLEY: Dorothy Roberts’ new book is called “The Mixed Marriage Project: A Memoir Of Love, Race, And Family.” Tomorrow on FRESH AIR, investigative journalist Vicky Ward spent decades investigating sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein. We’ll talk about the revelations in the Epstein files, the 3 million pages of documents that have been released to the public and the implications for survivors. I hope you can join us.

To keep up with what’s on the show and get highlights of our interviews, follow us on Instagram at @nprfreshair. FRESH AIR’s executive producers are Danny Miller and Sam Briger. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham. Our interviews and reviews are produced and edited by Phyllis Myers, Ann Marie Baldonado, Lauren Krenzel, Therese Madden, Monique Nazareth, Thea Chaloner, Susan Nyakundi, Anna Bauman and Nico Gonzalez-Wisler. Our digital media producer is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. With Terry Gross, I’m Tonya Mosley.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Paul McCartney’s decade of transformation: From Beatles breakup to John Lennon’s murder

Man on the Run shows McCartney's effort to define himself outside The Beatles' shadow: "Paul making this documentary was a way of coming to terms with that whole period," says director Morgan Neville.

A Biden-era rule sought to stabilize child care. Why Trump wants it gone

The Trump administration has proposed repealing a Biden-era rule that required states to change how they pay out child care subsidies, citing the potential for fraud.

Greetings from Southwest Papua, which has some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity

The Raja Ampat islands in Indonesia's Southwest Papua province are a marine biodiversity hotspot and a divers' paradise.

Families remember U.S. reservists killed in Kuwait, members of an Iowa logistics unit

Four U.S. soldiers were killed in the Iran war on Sunday and IDed Tuesday by the Pentagon; two soldiers haven't yet been publicly identified. Their unit kept troops supplied with food and equipment.

Why supporting a shelter for women is now ‘kind of radioactive’

That's how researcher Beatriz Garcia Nice describes the new U.S. stance under the Trump administration to programs addressing gender-based violence.

Telehealth abortion is in the courts. Share your experience.

Mifepristone is facing another major legal challenge.