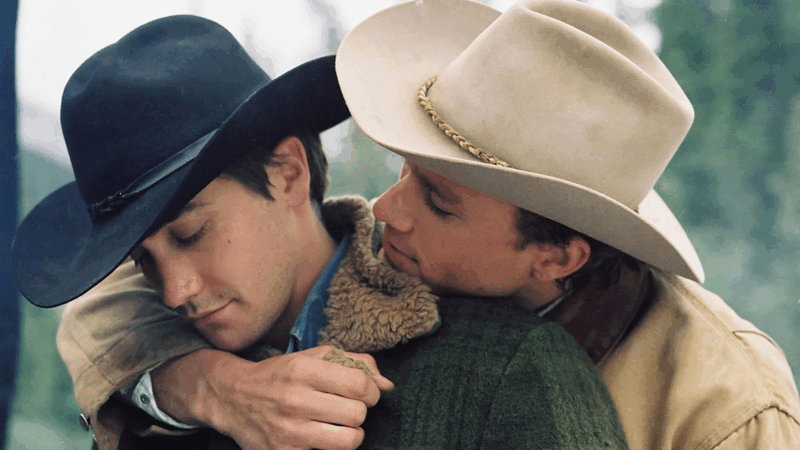

20 years later, is it time to quit ‘Brokeback Mountain’?

I was in my 20s when I read the original Annie Proulx short story “Brokeback Mountain” in The New Yorker; I was floored by it. First, because it was a Western. I’d spent years reading New Yorker fiction by then, and I didn’t think they went in for Western stuff. No, I figured their genre was more White Bougie Heterosexual Alcoholics in Muted Despair, you know?

I read further and met Ennis and Jack, two sheep herders who eke out a kind of strangled, self-loathing love story on the wind-whipped slopes of a mountain in Wyoming in the 1960s. I then realized why The New Yorker had published it — not so much the story, or the characters, or the setting, but the prose.

My god, the prose. So spare, so austere, so unsentimental — yet you could feel everything that was roiling just below its surface. The steely restraint hard-wired into every sentence was struggling to hold back a wall of emotion — feelings so pure and implacable that they terrified the story’s characters, Ennis especially. Which, duh, is why the story worked so perfectly, why reading it felt like slipping a callussed hand into a worn glove — the language of the story perfectly reflected the emotional state of Ennis, a man who’d wholly internalized a pinched, performative notion of masculinity.

When I read that they were making it into a movie — one that turns 20 years old this year — I figured they’d screw it up. How could they not? Movies can’t capture that kind of internal tension. Whenever they try to secure us a purchase inside a character’s head, they default to voiceover, which is clumsy and distracting. Then I read that nobody involved in the movie — not the screenwriters, director, or lead actors — were gay, and I figured: No yeah, this is doomed. (Today, we’d say that they “didn’t publicly identify as queer,” of course. For good reasons. But back then? Me and my friends? We just shrugged and said, “The straights are gonna blow it.”)

We didn’t talk about identity back then the way we do now. If they remade Brokeback today, the sexuality of the filmmakers involved would likely engender (heh) discussion in the wider culture, not just the queer community, like it did back then. That’s a good thing, generally.

It’s not, and never has been, about permission. Queer actors can play straight, and vice versa. Straight filmmakers can make movies about queer people. Anybody can make anything! What it’s about, however, is getting it right.

In the book Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay, Proulx writes a bit about the research she did, which included talking to her gay friends and one old sheep rancher who told her he always sent two men up on a mountain together to watch the sheep “so’s if they get lonely they can poke each other.”

The straights didn’t screw it up, as it turns out. Brokeback Mountain ended up being a great film, maybe even a masterpiece. We lost the throttled rigor of that magnificent prose, sure. But we gained Heath Ledger’s take on Ennis. Ledger created a character so guarded and cautious about expressing himself that, on those rare occasions he’s driven to speak, you watch him attempt to swallow the words before they escape. (Screenwriters Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana — smartly — took Ennis’s already laconic dialogue in the story and slashed it in half. When you go back and read it after seeing the movie, story Ennis comes off as a real Chatty Cathy.)

Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal captured the stuff that matters — lust shading into love, love decaying into heartbreak. Crucially, they also captured the thing that matters most to Proulx. In a 2009 The Paris Review interview, she said, “[The story] isn’t about Jack and Ennis. It’s about homophobia … it’s about a place and a particular mindset and morality.”

Throughout the film, Ledger quietly radiates fear, disgust and rage. He resents that his love for Jack can never be anything but a shameful secret, and he knows that he’s complicit in keeping it one.

So, yeah, they got a lot of things right. But not everything.

Yes, I’m talking about the sex. They, uh … get the angles wrong, if you follow me. I’m gonna have to leave it at that.

It’s something that occurred to me when I recently rewatched the film for the first time since it came out. I remembered how Bryan Fuller, the gay showrunner of the troubled series American Gods, insisted that one gay sex scene on that show be completely reshot, admonishing his director to “go back and figure out where holes are.”

I thought about the series Fellow Travelers, which was just as much about homophobia and shame and the threat of exposure as Brokeback is. But that show was a hell of a lot more honest about gay sex, and wasn’t afraid to make its sex scenes sexy. More importantly, it used the sex to show how the dynamics of the relationship between its two leads were constantly shifting, over the years.

That American Gods episode aired in 2017, and Fellow Travelers in 2023, which explains some of the difference in their approaches, compared to Brokeback. But both television series had plenty of queer folk both in front of, and behind the cameras. It matters, and here’s why.

I’ve talked to several younger queer folk who resolutely do not get Brokeback Mountain. To them, it reads as a cringeworthy, basic, middle-of-the-road attempt by straight Hollywood to tell a queer story.

And you know what I can’t help thinking? Maybe the film would work more for them, would feel more truthful and resonant and powerful, if, when they were filming those sex scenes, someone — anyone! — on the set had told them they were getting the damn angles wrong.

This piece also appeared in NPR’s Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter. Sign up for the newsletter so you don’t miss the next one, plus get weekly recommendations about what’s making us happy.

Listen to Pop Culture Happy Hour on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

GOP Rep. Tony Gonzales of Texas ends reelection bid after admitting to affair with aide

Republican Rep. Tony Gonzales of Texas said late Thursday he was withdrawing from his reelection race, after having admitted an affair with a former staff member.

Pentagon labels AI company Anthropic a supply chain risk

The Pentagon said in a statement Thursday that it has "officially informed Anthropic leadership the company and its products are deemed a supply chain risk, effective immediately."

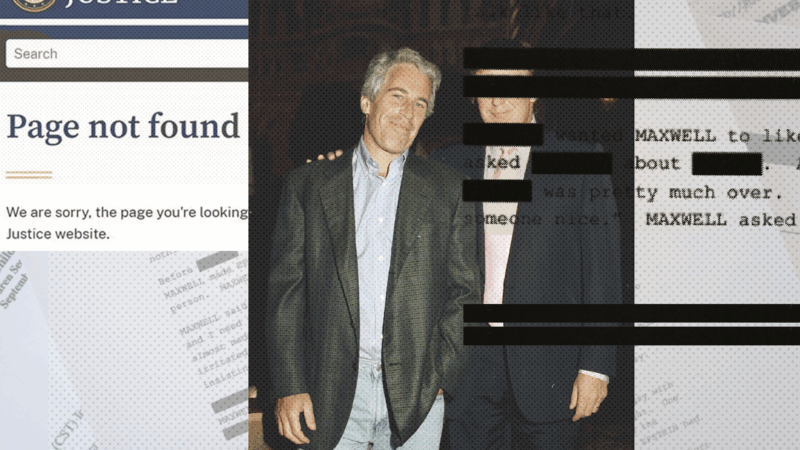

Justice Department publishes some missing Epstein files related to Trump

The Justice Department has published additional Epstein files related to allegations that President Trump sexually abused a minor after an NPR investigation found dozens of pages were withheld.

Pregnant women in ERs took less Tylenol after Trump autism warning

A study in The Lancet finds that pregnant women in emergency rooms used less Tylenol after President Trump said it could raise their babies' risk of autism. Scientists say there is no proven link.

Mixed reactions, including relief, greet news the Coast Guard is buying BSC campus

The U.S. Coast Guard will take possession of the 192-acre campus in the northeast corner of Birmingham’s Bush Hills Neighborhood and will begin work to refit it as a training center for officers and enlisted personnel.

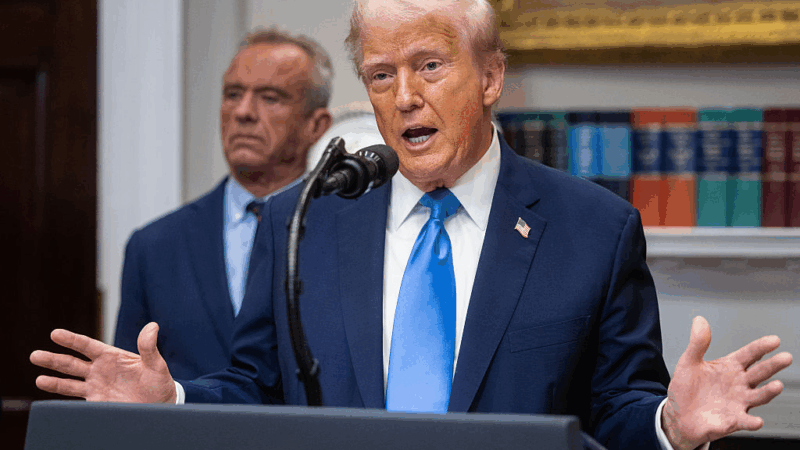

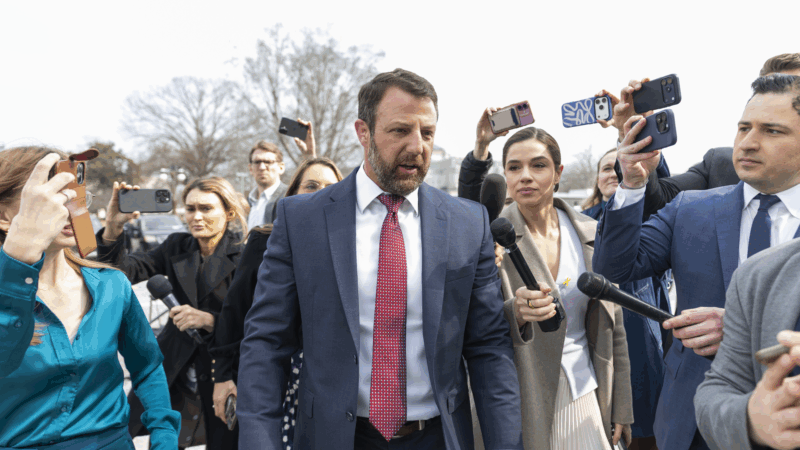

What you need to know about Sen. Markwayne Mullin, Trump’s new pick to lead DHS

President Trump announced Thursday that Sen. Markwayne Mullin, R-Okla., is his pick to replace Kristi Noem as the head of the Department of Homeland Security.