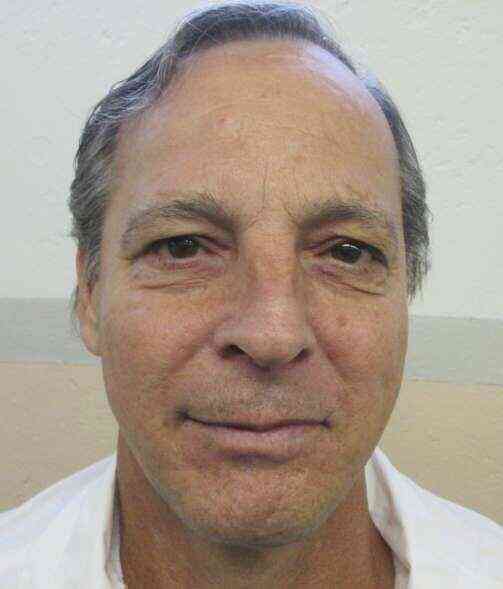

Alabama executes Gregory Hunt by nitrogen gas for 1988 murder of Karen Lane

The entrance to William C. Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore, Ala., which houses the state's men's death row, on Sept. 27, 2024

Alabama executed Gregory Hunt Tuesday evening, killing him with nitrogen gas after he spent more than three decades in lockups for a 1988 Walker County murder.

The execution marks Alabama’s third this year, on pace to match its six executions in 2024, which was more than any other state last year — though this year, Florida has already reached that tally.

Hunt, 65, was sentenced to death for the killing of Karen Lane, whom he had been dating for about a month, according to court documents. Prosecutors said she was sexually assaulted and beaten, causing broken ribs and other injuries.

In his final 24 hours, Hunt received visits from attorneys and an investigator. He declined his dinner tray, which had included hot dogs, vegetables, potatoes and black eyed peas.

As the curtain opened to the reporters’ viewing room at 5:52 p.m., Hunt appeared in the fluorescent-lit execution chamber on a gurney with seatbelt-like black straps secured across his chest and his wrists strapped down. His feet and lower body were wrapped tightly in a white sheet.

Hunt shook his head “no” when asked if he would like to make a last statement. Pool reporters saw him make a peace sign-like gesture.

A transparent plastic mask with black vents and blue borders covered his face. His eyes were closed as officials sealed his mask.

It was not clear exactly when the gas began flowing, and Alabama’s prisons commissioner John Q. Hamm later could not provide an exact time at a brief press conference. At 5:55 p.m. there was a slight beeping sound. Hunt blinked, closed his eyes and his chest moved up and down.

At 5:57 p.m. he began breathing more heavily and lifted his head up off the gurney. His left knee jerked up and his body shook. His head lowered then rolled to one side.

At 5:59 p.m. he lifted his head and feet into the air off the gurney, and they hung there for several beats. Then they went down and he became more still.

At 6:01 p.m. he seemed to breathe deeply as a member of the execution team bent down to look at his face. He appeared to take a few more full breaths periodically for the next few minutes. His left fist was balled tightly, while his right fist was not visible.

His last big breaths came around 6:04 p.m. He then appeared still until the curtain closed at 6:19 p.m. Hunt was pronounced dead at 6:26 p.m.

Hamm said the gas flowed for five minutes past “flatline.” He said Hunt’s shaking during the execution was “consistent” with other nitrogen gas executions, characterizing it as “involuntary body movement.”

“It was nothing we did not expect,” he said.

Hamm said approximately 10 of Lane’s family members were in attendance. He read and distributed a statement from the family to reporters, who said the evening was not “about the life of Greg Hunt.”

“This night is about the horrific death of Karen Sanders Lane, whose life was so savagely taken from her. Karen was shown no mercy, she was not given a second chance,” it read in part, adding that the night was “also not about closure or victory.”

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey and Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall released statements following the execution.

Ivey referred to Hunt as “undeniably guilty,” and said the state “stands with Karen Lane, and we pray her loved ones can finally find peace and closure.”

In a post on X, Marshall called the execution “a long-overdue moment of justice.”

“Gregory Hunt spent more time on death row than Karen spent alive,” Marshall said in a statement. “If he had any real evidence of innocence, he had more than three decades to present it. He did not. What he and his supporters offered instead was a last-minute spectacle aimed at rewriting history and distracting from the truth.”

To read the full release, click here: https://t.co/oeifpz1duq

— Attorney General Steve Marshall (@AGSteveMarshall) June 10, 2025

Legal disputes

Hunt was convicted of three counts of capital murder in 1990 following a jury trial, filings show.

He had lately made legal challenges to the case on his own behalf, called “pro se” filings. That included filings with the U.S. Supreme Court, requesting the court stay his execution.

The court denied that request hours before his execution.

In various court filings, Hunt made arguments including that prosecutors mischaracterized some evidence dealing with the sexual assault elements of his case. He also argued that recent Supreme Court decisions suggest his case should be reviewed.

Alabama’s attorney general said other evidence pointed to sexual assault, and that Hunt’s claims had been brought up before and were found “meritless.”

Following his conviction, jurors had disagreed in the penalty phase of Hunt’s trial, with a holdout juror not joining 11 others that voted to impose a death sentence, per court records.

Alabama and Florida both permit non-unanimous juries to greenlight a death sentence during the penalty phase, according to the nonprofit Death Penalty Information Center.

Previous attorneys for Hunt said in mid-2000s court documents that the trial lawyers had not presented key “mitigating” evidence about his past, which included an abusive family, time in group homes and drug use that began in childhood.

‘To save the lost’

Hunt’s execution comes amid a national spike in executions that has alarmed death penalty opponents.

That includes the executions of Anthony Wainwright, in Florida, scheduled for the same day as Hunt’s execution, John Hanson, in Oklahoma, on Thursday and Stephen Stanko, in South Carolina, on Friday.

Wainwright’s execution took place via lethal injection and he was pronounced dead at 6:22 p.m. ET — a little more than an hour before Hunt.

Hanson was granted a stay on Monday, but it is being challenged.

The Rev. Jeff Hood served as a spiritual advisor for both Hunt and Wainwright, he said, and thus could only attend one of their executions — choosing to attend Wainwright’s after Hunt told him he’d be OK without him in attendance.

Abraham Bonowitz, director of the national nonprofit Death Penalty Action, said many cases now moving forward are very old, and show the death penalty “catching up” as death sentences decline.

At the same time, there is a concurrent press to expand capital crimes and speed up executions of people on death row, he said. But he does not believe that will gain traction in the long run.

“They’re going to run out of people; they’re going to run out of desire,” he said.

Hunt’s execution was Alabama’s fifth overall using the nitrogen gas method, which has drawn rebukes from some physicians and human rights experts.

Alabama was the first state to use the method, which is on the table in Mississippi, Oklahoma, Louisiana and Arkansas, the latter of which legalized the method in March.

Among those other states, only Louisiana has used it during an execution, using nitrogen gas in March to put Jessie Hoffman Jr. to death in its first execution in 15 years.

President Donald Trump has moved specifically to expand use of the death penalty, signing an executive order that pushes for capital charges and directs the U.S. attorney general to help states gather lethal injection drugs.

That echoes the president’s first term, when 13 people on federal death row were executed in a matter of months.

In a phone interview before his death, Hunt said he thinks the death penalty persists because some pastors represent it as having God’s stamp of approval.

But as Hunt studied the Bible, he came to disagree. He called the figure of Jesus a “defense attorney” in religious texts, referencing a story about the Christian leader stopping a woman from being stoned.

“God is not imputing our sins upon us,” Hunt said. “He’s come to seek to save the lost, even scoundrels like me. You know what I mean?”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

India has long promised ‘vibrant’ border villages, as China speedily builds up

India's government launched a Vibrant Villages Programme almost four years ago. But as China steadily builds up its side, Indian residents wonder what's taking so long.

Longtime civil rights leader Rev. Jesse Jackson dies at 84

The Rev. Jesse Jackson was a lifelong civil rights advocate until his death Tuesday at the age of 84.

Minnesota Republicans defend their focus on fraud despite the ICE surge that followed

Minnesota Republicans say they were right to invite social media influencers into the state to highlight social service fraud, though Democrats blame Republicans for paving the way for the ICE surge.

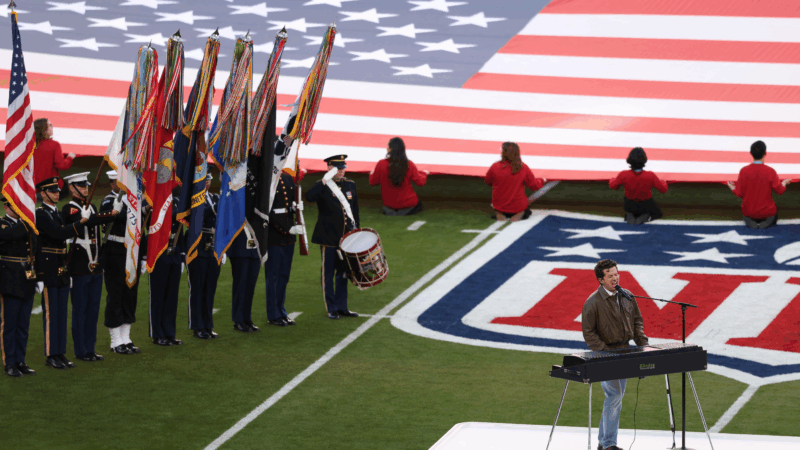

TV antennas and Super Bowl rehearsals: How prediction market traders seek an edge

As prediction markets boom, competition is heating up. So traders go the extra mile for a fraction-of-a-second advantage or to sleuth out information nobody else has. It can lead to a huge payday.

A once-underused immigration enforcement program has exploded under Trump

Partnerships between ICE and local law enforcement agencies has expanded widely, under the second Trump administration, data analyzed by NPR shows.

3 big changes are proposed for FEMA. This is what experts really think of them

The Trump administration is proposing massive changes to the Federal Emergency Management Agency. We asked disaster experts to weigh in.