New opera delves into less familiar part of Helen Keller’s story

Helen Keller has a special place in Alabama. Keller, who was blind and deaf, is on the state quarter and is depicted in one of the state’s statues at the U.S. Capitol. That statue references a well-known moment in Keller’s young life when her interpreter, Anne Sullivan, ran water over her hands while signing W-A-T-E-R into her palm until Keller understood the meaning of the word.

But Keller’s place in history goes beyond her disabilities. One aim of the opera TOUCH, commissioned by Opera Birmingham, is to highlight parts of Keller’s story that often go untold.

TOUCH takes place after Helen’s graduation from Radcliffe College. It covers her time as a burgeoning activist and political voice. But it’s mostly concerned with her complex relationship with Sullivan, who gets married early on in the show.

“I can’t imagine what Helen must’ve felt when this person, who was her conduit to the outside world, might be taken away from her,” said the general director of Opera Birmingham Keith A. Wolfe-Hughes.

He emphasized that though the opera includes facts about Helen’s life, it’s not a documentary. He said it’s the human story of these two icons who are always depicted as strong and unwavering.

“There is a story beyond ‘water, Helen, water,’” said Michelle Drever, who plays Sullivan in the production. “These are two unique, deeply feeling women who we see in the later phases of their lives.”

In TOUCH, both women find difficulty in accepting the other has a life without them. In spite of their close bond, they’re afraid of being outgrown. Their codependent relationship is what fascinated composer and librettist, Carla Lucero.

“I thought that there’s a certain part of the story where you understand that Anne had to be somewhat selfless. Her future would have been so bleak had it not been this opportunity to help Helen not just integrate into the outside world, but to succeed and excel,” she said.

The importance of (physical) touch

Their relationship borders on symbiotic. After all, Keller needed touch to communicate, keeping her and Sullivan constantly physically connected. But they’re also connected through their finances and their careers. When Keller gets married later on in the opera, it causes concern for Sullivan.

“Anne’s concerned about where the money’s gonna come from, or if Helen gets married and isn’t going out on the road anymore, what happens to her life?” Wolfe-Hughes said.

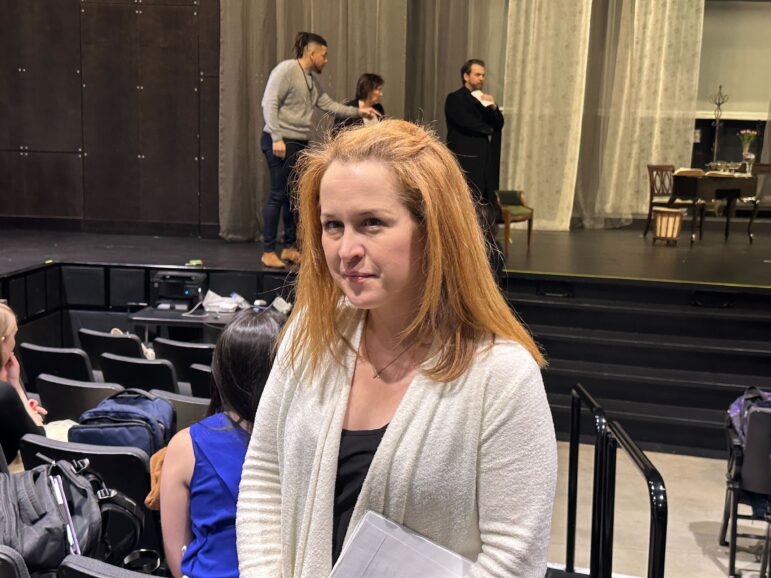

Keeping connection present on stage was essential for TOUCH. The director of the opera, Sara Widzer, is also an intimacy coordinator. This background helped her guide the cast through difficult dynamics and emotions. She shared anecdotes about families similar to the Kellers to share the performances.

During a rehearsal, Widzer directs a scene in which Keller’s mom is torn between accepting her and respecting her husband as they differ over how to care for their daughter.

“The delicate balance between husband to wife in this time period. But there are things your husband says to you, there are things that couples only have in the middle of the night, lying in bed, that there is a reason you acquiesce,” Widzer said.

She encouraged the cast to literally touch each other throughout the show.

The constant presence of physical embrace keeps Keller and Sullivan’s relationship always present on stage.

Tackling disability

Lucero wanted to take on a story that would challenge the lack of disability representation in musical theater. Her co-librettist, Marianna Mott Neworth, focused on accessibility. They sought out the help of two consultants with disabilities. One of those consultants became their lead actress.

Alie B. Gorrie plays Helen. Gorrie has low-vision but, despite this similarity shared with Keller, the role has been challenging.

“I’m still learning and navigating. How do you tell a story with just your body? It’s calling on a lot of actor tools and training.”

She says it gives her chills to play a character with a disability, who has an identity outside of it.

“So many Alabamians don’t realize that Helen Keller was one of the most dangerous women in America at one point in time. She was an activist, a feminist,” she said. “It’s her being a suffragist, and falling in love, and being a total human. Not just this one token.”

Keller doesn’t speak in the opera, but she’s still given a voice. Her thoughts are represented through a chorus.

“I first had the Helen character as not speaking or singing, but was there reacting. And when I saw the workshop I thought ‘this is not working for me,’” said Lucero. “So I made a radical change and decided to have four voices sing for Helen.”

Opera Birmingham is making this and all future shows more accessible. TOUCH will be interpreted in American Sign Language. Viewers will have the opportunity to choose Braille or large print programs. Even the show’s promotional image spells TOUCH in Braille.

“My biggest hope is that it inspires you to plug into the disability community, to show up in different ways, to go to your organization and say ‘wow, look at all these ways Opera Birmingham showed up for the disability community. How can we?’” Gorrie said.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

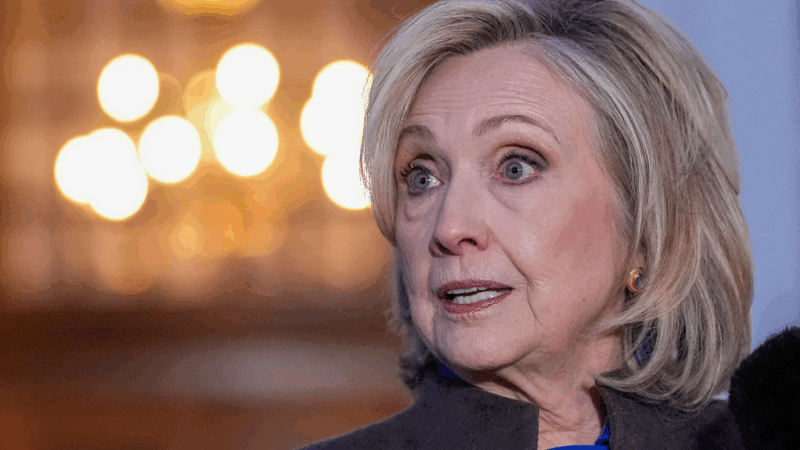

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.