The Gulf South’s record heat brought another pain for residents — higher power bills

This story is part of a crowdsourced project investigating utility billing issues in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. Do you have a utility bill that you’d like us to look into? Submit it here, and with your permission, we may use it in one of our monthly features.

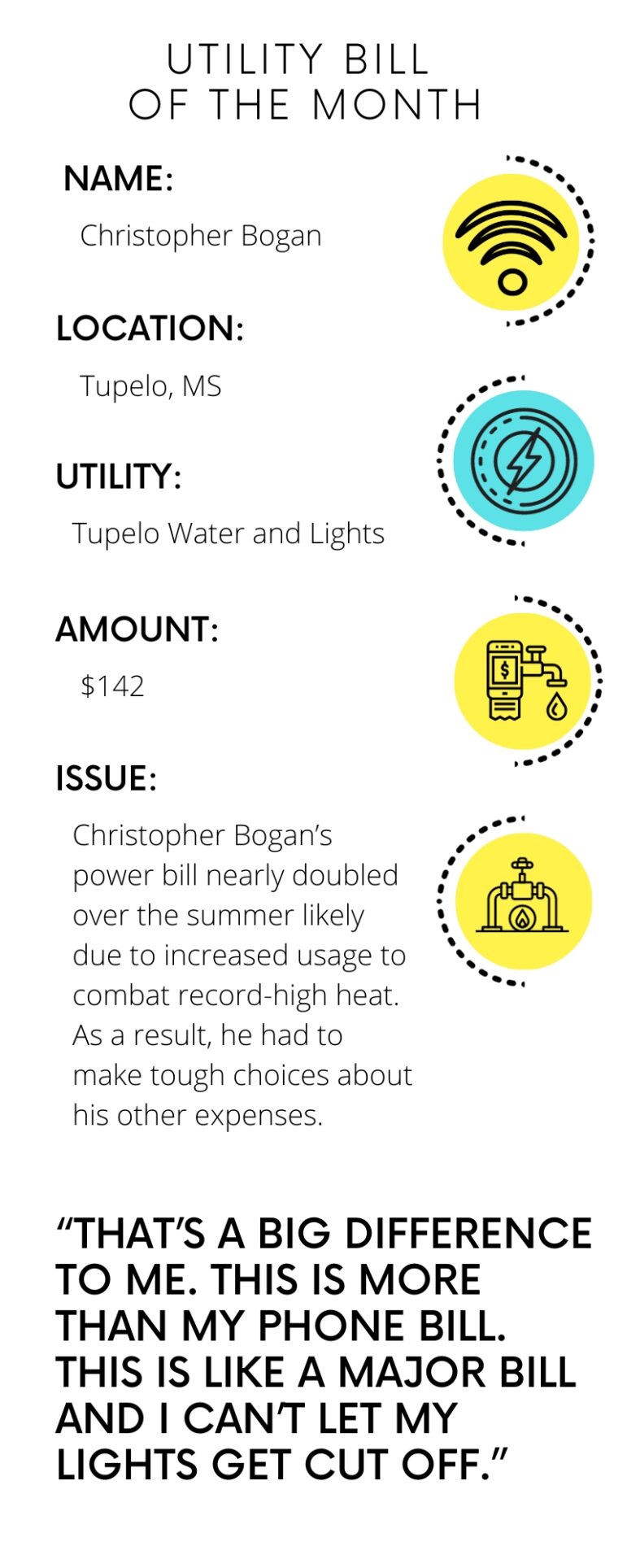

The straight A’s on Christopher Bogan’s report card were just what he needed after a rough 2022.

He’d ruptured his spleen last year and had to move back to his hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi, from Atlanta to recover. Since then, he’s worked to get his life back together by working two jobs, getting his own place and acing computer science classes online at Strayer University.

But those steps he took forward were met with a setback in June. His power bill for his one-bedroom apartment came in at $142 — nearly double what he paid in the spring.

“That’s a big difference to me,” Bogan said. “This is more than my phone bill. This is like a major bill and I can’t let my lights get cut off.”

Even before this summer’s record-high temperatures, one out of three people living in the South had trouble paying their power bills. Low-income renters in the region are often the most burdened by the jump in cooling costs since a larger cut of their budget goes to energy. While some states are experimenting with different policies to help customers, that type of aid isn’t as common in the South.

“Very few warm weather states have adopted these kinds of rules,” said Mark Wolfe, executive director of the National Energy Assistance Directors Association. “In the South, it’s really tough to get these rules in place.”

Adjusting the budget

Bogan took the first step toward getting a handle on his high power bills by himself — using less power.

Bogan raised his thermometer to 76 degrees F to keep his air conditioner usage down. But despite that, his July and August expenses also came in north of $140 — an amount that did not make sense to him given his apartment is no more than 650 square feet.

To cover the added cost, he adjusted his budget. He cut back on his food spending, and simple pleasures like clothes shopping. Buying anything he wanted could mean struggling to pay for necessities like rent. He’s also called Tupelo Water and Lights to defer paying his bill by a week to avoid a shutoff.

Before his power bill’s spike, Bogan had trouble playing catch up on his car note and also couldn’t afford his HIV medication.

“There are millions of folks that we already know are actually forgoing food or health care just to pay their energy bills in the South,” Maria Castillo, senior associate with the Rocky Mountain Institute, said.

Higher bills not surprising

Energy researchers said it’s not surprising to hear about power bills doubling this summer.

First, there are global factors, like the war in Ukraine, that have led to higher energy costs. Utilities, like Alabama Power, also raised rates earlier in the year. These changes come after electric bills already increased by 5% in 2022, which the U.S. Energy Information Agency largely attributed to steeper fuel costs.

Bills also went up simply because this Summer was really hot.

“The expectation was that this summer would be as hot as last summer,” Wolfe said. “That turned out to be wrong. It was hotter.”

This past August was the hottest on record for both Mississippi and Louisiana. Alabama also set records, including Mobile, Alabama logging its highest temperature the city has ever reported at 106 degrees.

Because of the high temperature and energy costs, NEDA estimated in July that the average home would go from spending $517 on energy bills for last year’s summer to $578 this year.

Cooling bills down

There are steps individuals can take to lower their summer bills. One is to make their home more energy efficient — like replacing the old, power-hungry AC unit or patching up the home’s insulation.

But renters don’t always have the option to modify their homes, and landlords can be reluctant to make changes that would mean higher rent — even if it saves renters in the long run. This is one of the reasons why lower-income Americans spend three times as much of their budget on energy than other households.

Another option is to do what Bogan did — nudge up the thermometer to use less AC. But the red needle can only be raised so much before it becomes dangerous, especially for those with health risks.

That’s why 18 states protect customers from having their power cut off when the temperature gets too high, according to Castillo. While Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi do this for cold temperatures, they don’t have any protections for the summer months.

“That’s one policy solution that feels like a no-brainer,” Castillo said. “Let’s not cut off anyone’s power when we know the consequences are deadly.”

At least seven states are also testing a cap on how much low-income customers have to pay for energy based on their budgets, Castillo said. California, for example, has a pilot program where participants don’t have to pay more than 4% of their household income.

The popular Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) also helps cover expensive energy bills, but the program does not have enough funding to cover everyone eligible for the aid. It was also envisioned as a way of helping with winter bills, but the hotter summers mean more households are asking for assistance in the warmer months, too.

And it’s not just that summers are hotter — they’re longer. September set a new global heat temperature for that month. For Bogan, that means the official end of summer did not provide any relief — his power bill still came in above $140 last month.

“We don’t know what’s going on with the world right now,” Bogan said. “I need to be prepared for this.”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

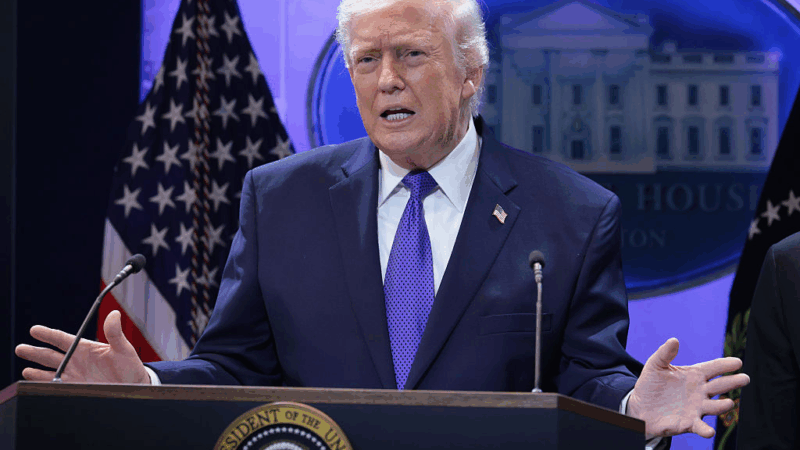

Trump to raise global tariffs. And, most say the state of the union is weak, poll says

President Trump says he is raising global tariffs to 15%. And ahead of the president's address tomorrow, most Americans say the state of the union is not strong, according to an NPR poll.

U.S. has a quarter fewer immigration judges than it did a year ago. Here’s why

The continued drain of personnel from the already strained immigration court system has contributed to depleted staff morale, mounting case backlogs — and floundering due process.

Poll: Most say the state of the union is not strong and the U.S. is worse off

Ahead of the State of the Union address on Tuesday, evidence continues to mount that President Trump is facing political headwinds.

The owners want to close this Colorado coal plant. The Trump administration says no

The Trump administration has ordered several coal plants to keep operating past their planned retirement, part of a larger effort to boost the coal industry. Two Colorado utilities are pushing back.

Influencers are promoting peptides for better health. What’s the science say?

The latest wellness craze involves injecting these molecules for athletic performance, longevity and more. Scientists say the research isn't keeping pace with the health claims.

Mexico fears more violence after army kills leader of powerful Jalisco cartel

School was canceled in several Mexican states and local and foreign governments alike warned their citizens to stay inside following the army's killing of the leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Nemesio Rubén Oseguera Cervantes, "El Mencho," and the violence it spurred