Q&A: Author of ‘Rocket Men’ details how Black quarterbacks helped move the NFL forward

Baltimore Ravens quarterback Lamar Jackson throws during the first half of an NFL football game against the Cincinnati Bengals, Sunday, Sept. 17, 2023, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Darron Cummings)

2023 marked the first time in NFL history that two Black starting quarterbacks faced off in the Super Bowl in February. Two weeks ago, nearly half of the league’s 32 teams were led by a Black quarterback in the opening week of the new football season.

So why did it take more than 100 years of NFL history to get here? That’s the subject of John Eisenberg’s new book “Rocket Men: The Black Quarterbacks Who Revolutionized Pro Football.”

The Gulf States Newsroom’s Joseph King sat down with Eisenberg to talk about the grueling journey of Black players and coaches in the league.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’ve written books about baseball, football, and I saw, even equestrian. What inspired you specifically to write this book focused on the Black Quarterback?

I remember going to the Winter Olympics in Calgary. We’re going back here, but like 1988, and there was a great black figure skater, Debi Thomas. She wound up winning, I think, a bronze medal. And so I just wrote columns about her. She was an incredibly graceful person to talk to and a great athlete and I wrote about her. So I come back from that and I’ve gotten horrible mail, just racist mail from people for me, picking on her because she’s Black, picking on me, I’m Jewish, and just awful stuff. If that doesn’t get your attention, nothing does.

What I’m trying to do with this book is shine a light on the fact that something happened in the NFL and for decade after decade, Black quarterbacks could not get on the field. The reason was just pure racist ideology, denial by stereotype. It happened, and it happened until more recently than people realize. So my goal with this book was to put it out there and to say, you know, let’s not quibble about any facts here. Here are your facts.

Why the title Rocket Men? Where did you get inspiration for that?

Rocket Men is a flattering title. I use it as a compliment. Lamar Jackson, Patrick Mahomes, the young guys that are coming into the league, all I gotta do is watch him play football and say, well, they’re Rocket Men, all right. They certainly have amazing skills. And the NFL’s never really seen guys like that.

I also wanted to use it as an homage to the guys that didn’t get a chance. This is a story of opportunity, and it’s an opportunity denied for many decades, and then finally, an opportunity granted by a white establishment. It’s really important to understand that there were guys that all they lacked was the opportunity. They had the talent, and so they were Rocket Men in their own way.

Many times Black quarterbacks were told they weren’t ideal quarterbacks for the NFL for a number of reasons. But why do you think the bar was higher for them?

You go back to the 60s, the 70s, the 80s. The NFL is an entirely white establishment. The owners still, the case, are almost entirely White. Coaches back then, all white. General managers, all white. Coming out of that era — the 50s and the 60s — there was a distinct lack of trust. They trusted Black athletes, had started to do that coming out of that era when the league was segregated and they reintegrated. However, by that point, football had modernized and offenses were getting sophisticated. There was a lot of passing and changing plays at the line. The playbook was getting fat and these coaches just said, ‘I’m not sure a black quarterback can handle the load mentally.’ That’s what they believed. Can he handle the load mentally? Can he lead? Can he be a leader? Can he come through in the clutch? All this stuff was just racist ideology based on nothing because none of them had played and had a chance to prove that it was wrong.

What was the most exciting moment you had in writing this book? Anything you learned behind the scenes that sticks out?

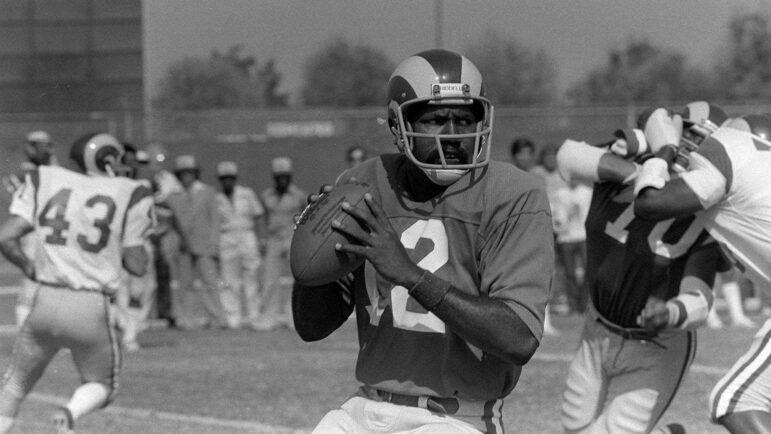

Well, the interviews are always great. I interviewed James Harris. He went on after his playing days to be an executive in the NFL and I got to know him a little bit and he just unpacks his story. He’s one of those classic Southern storytellers, and when I asked him what it was like to get drafted by the Buffalo Bills and fly up to Buffalo, in the summer of 1969, the same year they drafted O.J. Simpson, he starts telling the story. It’s incredible. He talks about going up there. They put O.J. up at a hotel. They put James Harris up at the YMCA for $6 a night. James didn’t have a contract. It’s not like football today. Eddie Robinson steps in and is negotiating his contract. Harris goes to the team and he says, “Hey, you know, I need a little money if I want to go get a sandwich or something.” They said, OK and they gave him a job cleaning his teammates’ cleats in the locker room. Just an unbelievable indignity that you could imagine today how that would go down, but he did it.

By the end of that training camp, he was a starting quarterback for that team. His talent came through. He got benched in the first game, and he never really played for the Bills, and it took another five years in the league for him to really get a chance with the Rams — and he did do well. But the story of him going to Buffalo in the summer of ’69 is amazing. When I finished with that interview, I thought, “Boy, I have a good book on my hands here because this guy has got stories that I just can hardly believe.”

Did any of the players and coaches who played in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi assist you with getting this story out?

Oh, absolutely. Tee Martin — he played at the University of Tennessee and won a national championship there and succeeded Peyton Manning. He would be one. Doug Williams, of course, needless to say — the first Black quarterback to win a Super Bowl from Zachary, Louisiana. Certainly, those two stand out to me. James Harris — he gave me just an incredible interview. And he’s from Louisiana as well.

You mentioned the differences with those players coming from HBCUs. Was there anything unique that you found about the experience of Black players in the South compared to other regions?

If you go back to the ’60s, the ’70s, there were no Black quarterbacks in major college football. So they were the ones, the HBCUs — some of them were just incredibly good. What was most interesting to me about that, I interviewed Upton Bell, who was a scout for the Baltimore Colts in the 1960s. His father had been commissioner of the NFL. Bell gets in his car from Baltimore, drives south. That’s what they did back then — there’s no [NFL Draft] combine or anything. He just went and scouted players.

He started going to the HBCUs and he would see these quarterbacks running and, of course, he’s much younger than the guys who have been scouting forever. He hears from the older guys, “Well, you know, he’ll be a good receiver.” Upton tells a story, he said, “You know, I’m looking at these guys, you know at Tennessee State and Southern [University] — they’re just all over the place.” He said in the mid-60s, “I’m thinking this quarterback is good. You know who are you kidding? He’s big, strong and he’s fast. And, you know, you talk to him, he’s a great kid.”

And he just realized that what was being said was wrong. And a lot of those guys at those schools could have played.

I saw you mentioned Ozzie Newsome, too. I know he’s not a quarterback, but anything specifically that he did?

He was a quarterback as a kid in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. He tells the story of how he went to tryouts, I think it was eighth grade. He was already a good athlete. He goes to tryouts and the quarterbacks are lined up in one place and the receivers are lined up in another line and he has to make a decision. He decided not to play quarterback, even though that’s what he’d always played on the sandlot. He didn’t want to do it because he knew what was going on.

It’s like, well, I’m a big, strong kid. I might be able to go somewhere in this sport, but if I’m a quarterback, they’ll make me change positions. It’s going to be a hard road, so I’m not going to play that position. And he became a receiver and a tight end and wound up playing at [University of Alabama] and then going to the Cleveland Browns. He’s in the Hall of Fame as a player.

What did the older players that you interviewed think about the state of things today?

They certainly wish they were making the money that today’s players make. That goes without saying. They think about the guys that didn’t make it. From Alabama, Condredge Holloway. He went to high school in Alabama and you know, we’re going back into the ’70s. I believe he was the fourth pick in that baseball draft, one year. Incredible athlete. And, you know, Bear Bryant told him there’s not going to be a Black quarterback at Alabama. I think this would be 1970 — around there. So he goes to [University of Tennessee] and he’s the first Black starting quarterback in the SEC. He could run, he could throw. He was a super sharp guy.

The quarterbacks from that era say, Condredge Holloway, in today’s football, would have been lights out. It’s perfect for him. However, in 1975 I think when he was eligible for the draft, he went in the last round as a defensive back and went to Canada because he wasn’t going to play quarterback in the NFL.

It’s crazy, you know, imagining turning a quarterback into a receiver. They have recently even, with Lamar Jackson, at the draft combine asking him if would he play receiver. And he’s like “No I’m a quarterback,” and he was a Heisman trophy winner.

Heisman trophy winner and second year in the league he’s the league MVP. But that’s part of the reason I wrote the book, to be honest with you. You go back to the beginning of asking me why. I’m in Baltimore and Lamar landed here right in front of me, and I’ve written sports forever, and I’m aware of that history.

It’s just incredible to me that we’re almost talking about 100 years of NFL football and people are still hearing that stuff. How did we get here? How did we get to the point where that is still going on? And I do think it’s changed even in the last five years. I think things are changing for the better. But Lamar, he heard it and he’s got a chip on his shoulder as a result.

The NFL season just started, and opening week we saw 14 starting Black quarterbacks. What’s changed in the NFL to get us to this moment?

2011. The draft that comes — you have Cam Newton and you have Colin Kaepernick come into the league that year. The next year, Russell Wilson, Robert Griffin III somewhat came out of the same mold.

They were big, they were fast, they were smart, they could throw. They were high draft picks for a reason and the NFL finally said we should not try and turn them into the next Tom Brady. That’s not going to work. We’re not going to make them change and possibly set them up to fail. What we’re going to do is change how we play offense. We’re going to change this position, we’re going to allow them to be more mobile. We’re going to use what they bring to the table and emphasize it, and in the long run, that really changed the position.

The #Ravens are believed to be the first team in NFL history to have an all-African American QB room, from players to coaches.

— Ari Meirov (@MySportsUpdate) September 5, 2023

From left to right…

• Assistant QBs coach Kerry Dixon

• QB Tyler Huntley

• QB Lamar Jackson

• QB Josh Johnson

• QBs coach Tee Martin

(📸… pic.twitter.com/WN2VsmIRV4

John Eisenberg is the author of the new book “Rocket Men: The Black Quarterbacks Who Revolutionized Pro Football.” John, again, thank you for talking with me today.

Well, thank you. I appreciate the time. And it was a lot of fun. I enjoyed it. Thank you.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

Deadline looms as Anthropic rejects Pentagon demands it remove AI safeguards

The Defense Department has been feuding with Anthropic over military uses of its artificial intelligence tools. At stake are hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts and access to some of the most advanced AI on the planet.

Hillary Clinton calls House Oversight questioning ‘repetitive’ in 6 hour deposition

In more than seven hours behind closed doors, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton answered questions from the House Oversight Committee as it investigates Jeffrey Epstein.

Chicagoans pay respects to Jesse Jackson as cross-country memorial services begin

Memorial services for the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr. to honor his long civil rights legacy begin in Chicago. Events will also take place in Washington, D.C., and South Carolina, where he was born and began his activism.

In reversal, Warner Bros. jilts Netflix for Paramount

Warner Bros. says Paramount's sweetened bid to buy the whole company is "superior" to an $83 billion deal it struck with Netflix for just its streaming services, studios, and intellectual property.

Trump’s ballroom project can continue for now, court says

A US District Judge denied a preservation group's effort to put a pause on construction

NASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

Why did a $72 million mission to study water on the moon fail so soon after launch? A new NASA report has the answer.