Garrett McQueen: The Sound of 13

When you think of classical music, what comes to mind? Maybe it’s a few male composers from a few counties in Western Europe. Garrett McQueen is here to change that perception. He argues that all cultures and people have music that should be considered classical, and that includes the diversity of all Americans. McQueen hosts The Sound of 13, a program which highlights classical music through the Black experience.

WBHM’s Michael Krall spoke with McQueen about the program, which airs this week (Feb. 20-24) from 8-9 p.m. as part of WBHM’s special programming in honor of Black History Month.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How diverse is the classical music world, whether we’re talking about composers, performers or audiences? I mean, I guess what I’m really asking here is, what are we missing out on?

Yeah, that’s a really great question. So over the past five or six years, my work has really centered around the idea of decolonizing classical music. And I know that that word can be a little intimidating for many people. But really what the point of it is that all around the world there are musical traditions rooted in the stories and the cultures of people, music that those folks consider “classical.”

So I applied that idea to the way I view classical music and even to the way that I view the use of that phrase. The music of Beethoven and Bach and Brahms … all of that music is really phenomenal, but it’s really just one aspect of the classical musics [sic] that exist all around the world.

So my long way of saying that the idea of classical music has been taught to us over the generations as an aesthetic rooted in the sounds of Western Europe. My job and my mission is to expand that, to include the musical aesthetics and traditions of all people and all cultures.

I imagine it takes a while from researching and discovering a previously unknown piece of classical music to recording it, getting it out to the public. So aside from listening to The Sound of 13, what can someone do today who’s interested in learning more and moving beyond the stereotype of classical music from a white male composer?

For me, the first step, what I encourage people to do, is to start where their interests are, what are, what’s the music that you love? What’s the music that you spend the most time with, and where did it come from? What inspired it? So, for example, let’s say I’m speaking with someone who loves the music of Beyoncé. I would encourage them to think about the ways that R&B today in the 20th century connects with the R&B of the mid-to-early 20th century, its connection to blues, its connection to field hollers and spirituals. And through that discovery, learning some of the names that made that music possible. I think the same goes for things like bluegrass and folk music, you know, whatever people like, especially here in this part of the world, there are routes to those aesthetics that reach far, far back into the most traditional aspects of American music.

You’ve been described as a classical agitator. What does that mean to you?

My view and my engagement of the field of classical music is one that’s a little less feelgood, maybe a little less soothing or relaxing, as many people tend to stereotypically think of classical music. I believe that for our society overall, to grow and to evolve toward wider unity and more equity, every single sector has to engage the traditions that it’s upheld, understand the degree to which it is tied to problematic systems of patriarchy and racism and pinpoint ways to sort of pivot away from those things. So for me, in classical music, I can’t help but to think about the fact that that phrase for most people elicits thoughts of Western Europe when, as I mentioned before, all cultures, all people have traditional musics, [sic] have music that is and should be considered classical. So when it comes to that title of classical agitator, I’m just always trying to shake the table to inspire dialogue and to help people think beyond what we’ve been taught to think about that phrase, classical music.

In terms of orchestras exploring the diversity of classical music, how can they make wider audiences feel included on the one hand versus, say, programming a piece by a Black composer that maybe could have the effect of, feel like you’re checking off a box, but yet there’s not as much repertoire by Black composers in the first place, or it just may not have come to light yet?

Yeah, I think the first step is understanding the difference between audience development and community engagement.

That’s very important. For multiple generations now, orchestras and other arts institutions have virtually ignored communities that they don’t see as being a contributor to their bottom line, if I can just speak frankly. So I think the first step is for arts institutions to understand that there’s a lot of work, there’s multiple generations of work to undo when it comes to engaging broader audiences.

Audience development is transactional. You know, we put this on the stage, you come and buy a ticket, and that’s the exchange. Community engagement is not transactional. So, my encouragement is for arts institutions to understand where the broader audience is that they’re looking for where they are first and foremost. And what’s the music, what are the arts, what are the different things that they are currently engaging, doing the work of creating that rapport and building those relationships and letting those relationships be the springboard for what goes on the stage. Simply putting on a concert filled with music by Black composers, that in itself isn’t going to do the work. It’s engagement, it’s dialogue that’s going to help people understand that there is something for them in in classical spaces. And that really has to be the starting point of the work. I do believe we’re seeing that across the board with orchestras, even with radio stations, in the way that things are being programmed. But at the end of the day, it all begins with the building of those relationships. And if there’s going to be a future of a concert hall really looking like the demographic of the city that it exists in, it’s going to have to start with building those personal relationships on the ground.

You’ve said that you can’t talk about classical music without talking about race. Can you tell me about maybe both an obvious and a subtle way that racism has impacted classical music?

So in my early days of radio, I really fell in love with the music of Frederick Delius. I love the story of a man from England whose parents wanted him to take on the family business, but he had other plans. He wanted to write music. So, you know, his parents sent him to Florida to manage an orange farm, as I was originally taught. And of course, while he was in Florida, he spent much of his time writing music. And that’s how we got his famous “Florida Suite.” So, you know, through more research and more study, it came to light for me that that orange farm was actually an orange plantation and that the music that he wrote that inspired his “Florida Suite” was in itself inspired by the Negro spirituals that he was hearing, the Black music that he was hearing on that plantation. That is a minor detail in some people’s eyes, the difference between an orange farm and an orange plantation. But from my view, racism is specifically linked with the way that that history has been taught and the degree to which folks like me have to relearn and unlearn to get the true story.

There’s also the famous story of Antonín Dvorák coming to the United States in the late 19th century to help Jeannette Thurber, who invited him, codify exactly what American classical music is. I don’t have the quote right in front of me, but in essence, Dvorák said, You know, there is no building an American School of music without centering the perspective and aesthetics of Black music. He understood that immediately. And of course, those sounds inspired much of his chamber music as well as his Ninth Symphony. So if we you know, fast forward to today, we haven’t taken Dvorák’s advice. We haven’t centered the Black perspective in what we consider classical music.

And of course, that’s due to Jim Crow, that’s due to Black codes following Reconstruction. That’s due to everything that we are continuing to see in in this country. So when we think about that phrase, classical music and the aesthetics that come to mind when we use that phrase, for me, it’s directly connected with broader racist structures, broader patriarchal structures that teach us that the greatest music, the finest music is by a certain number of men from a certain few countries in Western Europe.

Understanding the role of racism in that I think is required in our understanding of how we can engage broader audiences through this medium moving forward. Once we’re honest with ourselves, once we are able to really understand the relationship between the history of classical music and the history of racism, I believe we’ll have the answers that we need to create programming that does actually engage who we are as Americans and all of our diversity and ultimately benefit not only audiences but the arts institutions themselves.

You’ve written that Handel made financial investments in the slave trade and that allowed him to write “Messiah.” You just referenced English composer Frederick Delius. How should we approach art with complicated histories?

Two thoughts on that. The first thought is that we have to bring those histories to light. We can’t allow racist histories or anti-Semitic histories as we’re continuing to talk about, take a back seat to an aesthetic or a piece of music that we’ve grown to love or just grown to become used to hearing on a regular basis. If we put the experience first, it will force us to consider how those stories should play a role and the way that we engage those pieces of music. But more directly, Handel’s “Messiah” is something that is performed and broadcast every holiday season. There are so many other works to put in its place that aren’t so complicated. It gives us the opportunity to put something on stages and through our radio airwaves that we don’t have to apologize for. Music and composers that don’t have complicated histories.

So just looping back to Handel and “Messiah” for just a moment. I’m just curious, are you suggesting that certain composers or pieces with a complicated history not be played at all, or perhaps we should just have a broader understanding of the circumstances surrounding these people, surrounding classical music?

Yeah, I guess my personal opinion is that there’s too much music in the global repertoire of classical music to continue to center composers and stories that are complicated. If we never programmed Handel, Haydn, Bach, Brahms or Beethoven again, we would still have more music than we’re able to platform and share with our audiences. So, there will never be a shortage of music by putting those traditions on the shelf. That’s my personal opinion. I also understand that arts institutions have audiences that aren’t ready for that sort of flip-of-the-switch engagement of new music. So I can say that I’m not completely opposed to the gradual shift or the slow incremental integration of a more expanded view on the programming. But for me personally, I do believe that there’s far too much music out there that we don’t have to apologize for to continue to platform music that we do have to apologize for.

Can you just describe a little bit more about some of the episodes that we’re going to hear?

The first of the five I titled Take Me to Church. So when it comes to the musical tradition of the United States, not just Black folks, but the United States in general, the Negro spiritual really is the bedrock of what this part of the world has uniquely contributed to the world of classical music.

And the next one, I titled it A Musical Founding Father. So, when we get into the evolution of the spiritual, into blues and to gospel, we do eventually, of course, get to what many people call jazz. Duke Ellington, for many people, is the sort of godfather of that tradition. And what many people don’t know is that he did indeed write a number of orchestral compositions. So that episode features not only the sounds of jazz and how that blends with the more traditional classical aesthetics, but Duke Ellington’s unique take on writing for orchestral music.

In the next episode titled Women of the Movement. I wanted to do just that, celebrate Black women in Western classical music here in the United States. We tend to think of composers as men, at least we have traditionally speaking. So in this series, I wanted to intentionally shine a light on the Black women who have also contributed to this art form.

In the next episode, I wanted to shine a light on the movies. I’ve found a lot of success in movie music programming, both on radio and in live concert, and Black composers have done a lot in that regard themselves. So for The Movies episode we have works by Quincy Jones, Terence Blanchard, and more composers who have had great success who may not always be approximated to the idea of classical music, but have certainly engaged the orchestral medium in that way.

And in the final of the episodes that I’m sharing with you. I titled it The Motherland. I wanted to make sure that I celebrated the diaspora in a way that shines a light not only on the Afro-American story, but music that points all the way back to the African continent. So that’s a little bit about the five episodes that you’ll be hearing from the series in general.

Garrett McQueen is the host of The Sound of 13. It’s a program addressing racial injustice in our society through the lens of classical music. Garrett, thanks so much for joining me.

Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

Surgeon general nominee Means questioned about vaccines, birth control and financial conflicts

During a confirmation hearing, senators asked Dr. Casey Means about her current positions and her past statements on a range of public health issues.

This novel about family drama is so good you may want to re-read it immediately

Allegra Goodman's new novel is called This Is Not About Us, but critic Maureen Corrigan says that title is coy: Readers are bound to see aspects of themselves and their families in these pages.

Actor Stellan Skarsgård doesn’t believe in bad guys

Skarsgård plays a filmmaker struggling to connect with his two grown daughters in Sentimental Value. As the father of eight, the Swedish actor says he understands the tension his character faces.

Kalshi reveals insider trading case against editor for MrBeast

With prediction markets booming, so have concerns about insider trading. Now, Kalshi has disclosed its first public actions against accounts suspected of trading on confidential information.

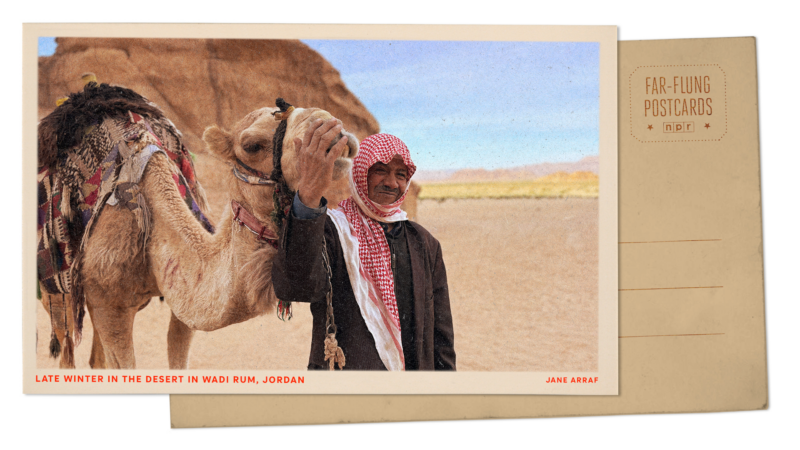

Greetings from Jordan’s Wadi Rum desert, where patches of green emerge after winter rains

Wadi Rum's otherworldly landscape is where Star Wars movies and The Martian were filmed. In late winter, plants emerge in this desert — but some are toxic to camels, so their herders must protect them.

Lack of transportation keeps many Alabamians from working. Rural public transit programs are trying to help

While lack of transportation is a major employment barrier in Alabama, few people take public transit to work. That dynamic is even more pronounced in rural areas.