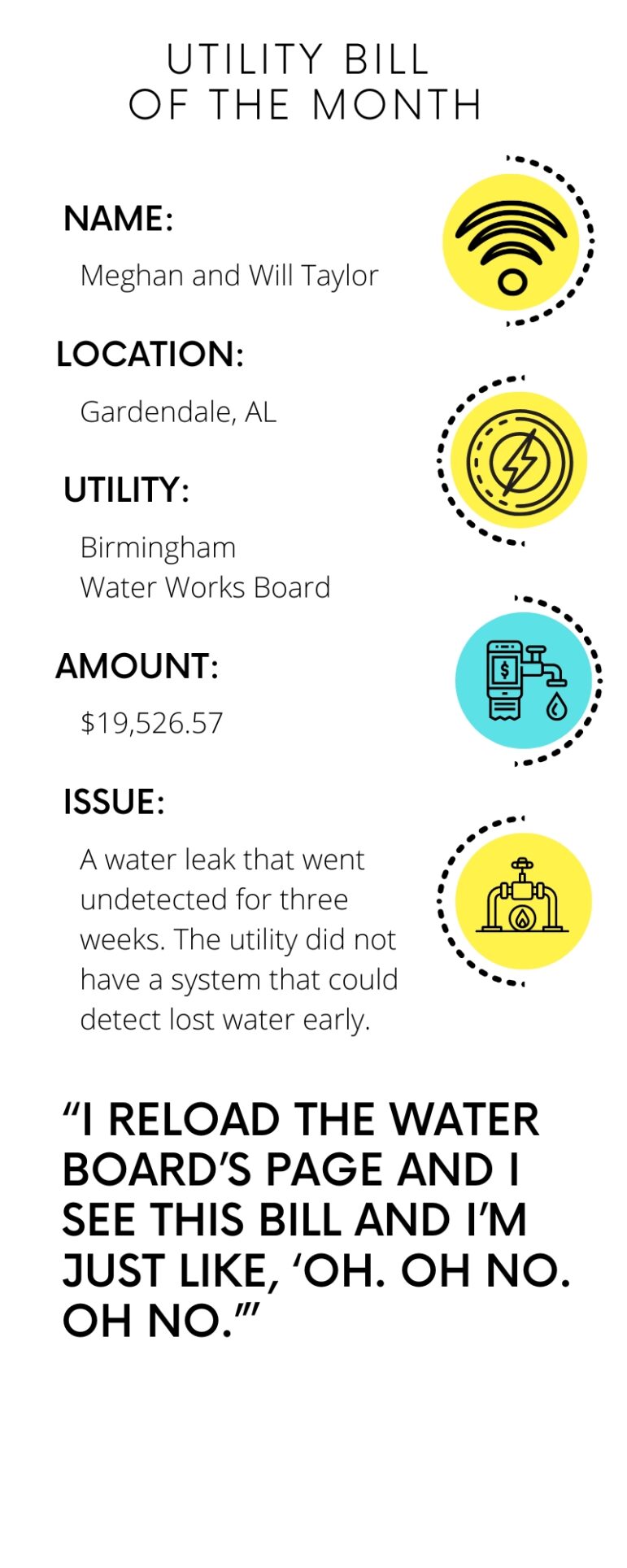

A water leak led to a $20K bill for an Alabama couple. A smart meter could have saved them

Meghan and Will Taylor, and their cat, hang out in the backyard of their new home on Wednesday, May 31, 2023, in Gardendale, Alabama. Last year, the Taylors received a water bill of just under $20,000 from the Birmingham Water Works Board after a catastrophic leak.

This story is part of a crowdsourced project investigating utility billing issues in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi. Do you have a utility bill that you’d like us to look into? Submit it here, and with your permission, we may use it in one of our monthly features.

Will Taylor was a nervous wreck. For two months in early 2022, he checked his phone daily to reload his account for the Birmingham Water Works Board (BWWB).

A serious leak at the Gardendale, Alabama townhouse he was renting had gone undetected for three weeks. It was bad enough that he suspected it could cost him and his wife, Meghan Taylor, thousands of dollars.

“And one day at about 10 o’clock, I reload the water board’s page and I see this bill,” Will said. “I’m just like, ‘Oh. Oh no. Oh no.’”

The actual bill was $19,526.57. The Taylors had been saving up to buy their own home soon, but this expense washed away any hopes of homeownership in the coming years.

“As young professionals in our 20s, $19,500 is not something we consider easily payable,” Meghan said.

The Taylors weren’t just shocked by the amount, but that the BWWB failed to detect the leak. An Olympic-sized swimming pool’s-worth of water going to one townhouse should have raised some alarm.

Water experts say smart meters, which automatically keep track of and transmit how much water a home uses, could have helped in the Taylors’ situation. But Birmingham’s water utility — like many others in the Gulf South — doesn’t use smart meters.

The “smart” label for meters simply means a way to send a wireless signal from the box to a central billing system — not something that sounds groundbreaking in the 5G era. When it comes to electricity, most customers already have smart readers installed. But for water, the norm is still having a worker physically go to each house and read the water meter box.

In theory, that happens once a month, but in practice, customers can go months without readings. The infrequent checks make detecting leaks harder and can lead to huge bills for individuals like the Taylors, who don’t receive an alert for a significant leak until the bill arrives.

“Water is, [about] 10 years behind electricity,” said Allen Berthold, the interim director for Texas Water Resources Institute. “The reality of it is, it’s just very challenging to do.”

‘Round and round and round’

The Taylors discovered their leak in early 2022 when they hired a plumber to fix a dripping shower head. When he went to turn off the water at the meter, he noticed a much bigger problem. The pipe had split just on their side of the property, and their water meter was counting it all.

“You could actually see the needle on it going round and round and round,” Meghan said.

They suspect it had been going on for three weeks, with the flooding water dumping directly into a storm drain so it went unnoticed. According to a clause in their lease, the landlord must fix the pipe, but they had to cover the bill.

According to the couple, they called the BWWB to let them know what happened and were told nothing could be done until the utility processed a bill. Any sort of adjustment could be talked about after that.

The bill ended up coming in about a month late — BWWB has a history of late and missing bills. The water provider acknowledges it needs to regain its customers’ trust and last month launched a campaign promising it will dedicate more workers to helping them understand their bills.

The utility did not respond to a request for an interview or to give a statement about the Taylors’ bill. But, when asked to confirm the bill, a spokesperson said the Gulf States Newsroom would need to use the last four digits of the account holder’s social security number to access it. The Taylors shared a physical copy of their bill, instead.

More than half of the cost came from sewage charges, so Will argued that part should be completely dropped since the leaked water never made it to the sewer. BWWB reduced the rest of it down to cost, leaving the final balance as $3,976.65. It’s still a huge water bill, but after weeks of phone calls and emails, the Taylors decided to pay it.

Will Taylor said he thinks what the utility did was fair. They shaved off about 80% of a bill that was ultimately the Taylors’ responsibility. But he’s still surprised that there is no alert system for leaks like this. After all, if it wasn’t for that leaking shower head, the leak could have gone unnoticed for an extra month since it took that long for a water meter reader to check the property. The Taylors could have faced tens of thousands more on that initial bill.

“Some sort of smart reader in place that could tell you, ‘Hey Will, you’re using 10 times more water this month than you were last month. Is everything okay?’ Something like that could have prevented this way before 800,000 gallons of water had gone down the drain,” he said.

How smart meters work

Hiring workers to physically read the meters at each property isn’t just a problem because it’s expensive. A shortage of workers in cities like New Orleans has caused its water utility — the Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans — to switch to alternating cycles of in-person readings and estimated billing.

Smart meters, alternatively, can take a reading every hour. Combine this with software monitoring usage and a smart system can make tracking down leaks easier and faster — essentially the early detection system Will Taylor said could have prevented his leak from going on for three weeks.

It can also help catch leaks on the utilities’ side too. U.S. water utilities lose about 17% of their water to leaks before it reaches their customers, according to one report.

But this kind of tech is a lot harder to set up for water compared to electricity. Unlike power meters, water meters are underground and usually covered by a metal lid, making it harder to send a signal out. They also don’t have a built in-power source like their electric counterparts, so they need a battery strong enough to send off the signal. None of this makes smart metering impossible, just expensive, and many water providers have been hurting financially for a long time.

Jackson’s smart meter woes

Smart readers are not infallible. Things can and have gone wrong with them, like they did in Jackson, Mississippi.

In 2013, Jackson contracted with water infrastructure company Siemens to install new smart meters and a billing system to go with it. Siemens promised the city the system would save it $120 million, according to the Jackson Free Press. But after the installs, many customers either saw their bills go missing or they were just wrong and absurdly high.

Eventually, the city sued Siemens and its subcontractors before reaching a $89.8 million settlement with the company. Part of the lawsuit accused Siemens of using Jackson as a testing ground to pair their billing system with the smart meters — a test that ultimately failed.

But Jackson’s smart meter woes were ultimately an exception, according to Alex Loucopoulos, a private water infrastructure investor. Loucopoulos said the tech has proven itself by now, and many big-city water providers have been quickly switching over. New Orleans recently began adding in smart meters, with plans to sub out all 140,000 of its older meters over three years. BWWB is in the early stages of discussing a possible upgrade.

Loucopoulos said sticking with or going back to traditional meter readings doesn’t make sense.

“It’s like if I sat here and told you to stop using Netflix. Let’s go back to using a VCR, or even worse, let’s go look at Betamax,” Loucopoulos said. “Smart metering… is sort of a no-brainer.”

Jackson did contract a different company — Sustainability Partners — to install new smart meters starting in early 2021. About 70% of the city’s meters have been replaced, and the full system is expected to be finished by early 2024.

Septic tank dream home

Despite the nearly $4,000 setback, the Taylors did manage to become homeowners last summer. Meghan described the new place as a beautiful home with big trees. She was also thrilled it checked an important box on her dream home checklist — a septic tank.

The lack of sewage fees was nice, causing their water bills to drop from around $100 monthly — when it wasn’t the cost of a new car — down to about $45. But, most of all, the Taylors wanted to deal with BWWB as little as possible.

“The less I can deal with them, the better,” Will said.

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR.

‘One year of failure.’ The Lancet slams RFK Jr.’s first year as health chief

In a scathing review, the top US medical journal's editorial board warned that the "destruction that Kennedy has wrought in 1 in office might take generations to repair."

Here’s how world leaders are reacting to the US-Israel strikes on Iran

Several leaders voiced support for the operation – but most, including those who stopped short of condemning it, called for restraint moving forward.

How could the U.S. strikes in Iran affect the world’s oil supply?

Despite sanctions, Iran is one of the world's major oil producers, with much of its crude exported to China.

Why is the U.S. attacking Iran? Six things to know

The U.S. and Israel launched military strikes in Iran, targeting Khamenei and the Iranian president. "Operation Epic Fury" will be "massive and ongoing," President Trump said Saturday morning.

Sen. Tim Kaine calls on the Senate to vote on the war powers resolution

NPR's Scott Simon talks to Sen. Tim Kaine, D-Va., about the U.S. strikes on Iran.

Iran strikes were launched without approval from Congress, deeply dividing lawmakers

Top lawmakers were notified about the operation shortly before it was launched, but the White House did not seek authorization from Congress to carry out the strikes.