Students and faculty nervous about Birmingham-Southern’s financial stress, possible closing

After one semester at Birmingham-Southern College, freshman football player Sam Wall didn’t expect his first year could be his last.

“It kind of just caught me off guard,” Wall said. “I love that I’ve created such a bond with that place already and in just one semester it’s like, I don’t want to imagine myself anywhere else.”

Late last week, officials at Birmingham-Southern revealed the campus could close as early as next year due to years of financial stress coming to a head this semester. The private college is now asking for $37.5 million in public money — $30 million from the state and $7.5 million from the local government — to keep its doors open.

Wall said he doesn’t want to lose the friends and connections he’s made at school, and while some of his classmates might have other options for school and sports, he doesn’t see that for himself. The school closing would put Wall and the other 1,058 students at the college in a difficult situation.

“I mean the Plan B — I’m not really sure what it would be,” Wall said. “It would kind of leave me at a crossroads, you know, I could just not go to school. I could get a job.”

He said maybe he’ll fall back on other schools he applied to. But Wall’s parents moved to be closer to him in Birmingham and he doesn’t want that to be for nothing.

“So the backup plan really is to just back up the school,” Wall said. “Try to be as supportive as possible and just ride or die.”

This is not the first time Birmingham-Southern has struggled.

Joelle Phillips, vice chair of the Board of Trustees, said the college has been trying for years to fix the financial troubles that started almost 20 years ago — when administrators had a plan to update buildings on campus.

“Unfortunately, many of those projects overran the budgeted costs,” Philips said. “And the college drew from the endowment to cover those costs. And then, of course, right after that we hit the 2008 economic downturn.”

Phillips said it was bad timing. In addition to that, an accounting error in 2010 forced the school to cut faculty, staff and five majors. Most recently, school President Daniel Coleman said the college has secured $45.5 million in pledges out of $200 million needed to keep the school open.

That money would go to Birmingham-Southern’s endowment, which anchors the college’s finances. Phillips said a college of BSC’s size can not sustain itself without an endowment that can cover 20% of operating costs, and right now the school doesn’t have that.

Phillips said she’s optimistic lawmakers will come through with the money and adds there’s precedent for the state to help private institutions.

“The American Rescue Plan Dollars and the Education Trust Fund have lots of precedent for policymakers deciding [that] investing in this is good for the entire kind of ecosystem of education,” Phillips said.

A couple days after the college’s financial problems came to light, Birmingham-Southern leaders held a meeting with Jefferson County lawmakers to discuss a plan to save the school.

“It was great to hear among the delegation across party lines, that there was real consensus that this is very important and that they feel that they can convince their colleagues in the legislature that this would be a wise investment to make,” Phillips said.

Glenny Brock, adjunct English instructor, was at the meeting and said she feels more hopeful now than before she went in, but there’s still a lot of uncertainty.

“I feel anxiety for my colleagues and for my students because this is so disruptive,” Brock said. “It’s so nerve wracking.”

Brock was aware the college was struggling financially and over the past few years Birmingham-Southern has also seen enrollment drop, which cuts revenue for a small liberal arts college. But she said it was still “shocking and distressing” to hear that the college could close.

Brock thinks the college’s salvation may lie in the fact that many BSC graduates stay in Alabama and contribute to the state’s economy. As an alumna, she’s a prime example.

“The place that made so many of us really needs help right now,” Brock said. “It is worth the help because of what the people who graduate from there pour in not just into Birmingham, but into cities all over the state and all over the world.”

Brock is optimistic the state will recognize that if lawmakers pour into Birmingham-Southern, Birmingham-Southern will pour back into the state. While there’s hope from these college officials and faculty, graduates looking from the outside are concerned about what might happen.

“I was devastated, actually I was pretty emotional about it,” said Lindsay Warren, a 2005 graduate of Birmingham-Southern. “Birmingham-Southern means a lot to me and a lot of other people that I know. So it would be a terrible, terrible thing if it closed.”

According to Warren there was no information readily available to alumni about the situation. Anna Sullivan, another 2005 graduate, said she felt a little in the dark.

“They’ve had some financial troubles in the past and they can’t seem to get it together,” Sullivan said.

Many people in Sullivan’s family went to Birmingham-Southern, so they have a lot of pride in the school. She wants the state to help the school in whatever way it’s helped schools like BSC in the past, but she has frustrations.

“I wonder if there would be any kind of opportunity for alum to be able to give back,” Sullivan said.”But, again, it’d be a little bit daunting to decide to give money to an institution that appears to be not handling the money correctly.”

Ultimately, Sullivan hopes for more transparency moving forward from Birmingham-Southern.

Clarence Barr, class of 2022, was not surprised to learn BSC was struggling, but didn’t know how much the school was in debt. He noted the school had five presidents in the last 10 years and knew they were struggling with enrollment during COVID.

Barr, a graduate of the business school, wants Birmingham-Southern to stay open, but he has concerns about taking money from the state.

“I worry that [if] they ask for a state infusion, that leaves more room for more legal argument for state influence,” Barr said.

Barr was happy with the school’s response to COVID by charging students a fee if they were not vaccinated. But he fears Birmingham-Southern won’t have the power to make those kinds of decisions if they get money from the state.

“There’s always been a history of: the more tax money that goes into a private institution, the more influence the government has in that institution,” Barr said. “Or at least that’s how it’s been in the past. I don’t know how it works for schools, but that’s a concern of mine.”

Barr is optimistic that current leadership will be able to fix this problem.

“I do trust Coleman. I actually never had him as a teacher, but I talked to him quite a bit,” Barr said. “I am glad that he is there to handle this whole thing. If anyone is going to fix it, it would be him.”

Lawmakers expect to present a plan to Governor Kay Ivey in the coming months.

Kyra Miles is a Report for America corps members covering education for WBHM.

U.S. and Iran to hold a third round of nuclear talks in Geneva

Iran and the United States prepared to meet Thursday in Geneva for nuclear negotiations, as America has gathered a fleet of aircraft and warships to the Middle East to pressure Tehran into a deal.

FIFA’s Infantino confident Mexico can co-host World Cup despite cartel violence

FIFA President Gianni Infantino says he has "complete confidence" in Mexico as a World Cup co-host despite days of cartel violence in the country that has left at least 70 people dead.

Supreme Court appears split in tax foreclosure case

At issue is whether a county can seize homeowners' residence for unpaid property taxes and sell the house at auction for less than the homeowners would get if they put their home on the market themselves.

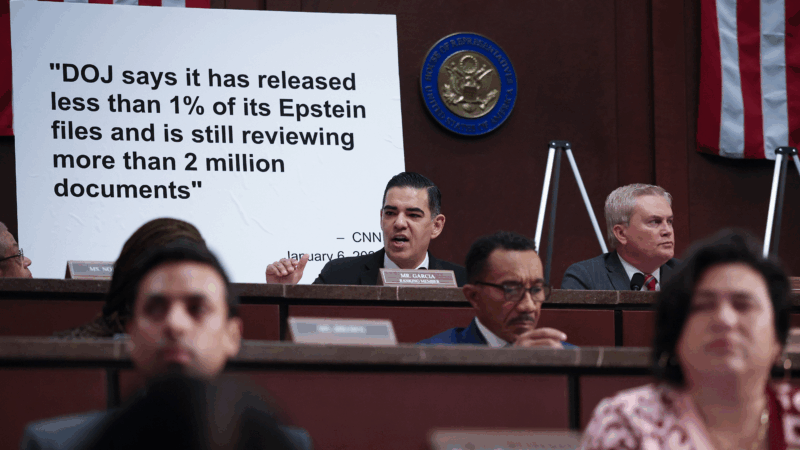

Top House Dem wants Justice Department to explain missing Trump-related Epstein files

After NPR reporting revealed dozens of pages of Epstein files related to President Trump appear to be missing from the public record, a top House Democrat wants to know why.

ICE won’t be at polling places this year, a Trump DHS official promises

In a call with top state voting officials, a Department of Homeland Security official stated unequivocally that immigration agents would not be patrolling polling places during this year's midterms.

Cubans from US killed after speedboat opens fire on island’s troops, Havana says

Cuba says the 10 passengers on a boat that opened fire on its soldiers were armed Cubans living in the U.S. who were trying to infiltrate the island and unleash terrorism. Secretary of State Marco Rubio says the U.S. is gathering its own information.